England’s 42 Anglican Cathedrals share a tumultuous political history, or tapestry, which plays out in each unique Cathedral Story.

It all starts with the Romans, a sophisticated and organized bunch if ever there was one. Their aqueducts provided running water, their arrow-straight roads were laid on rock-solid foundations, and their society operated from an equally sound legal framework on which today’s common law still rests.

Christianity came to England following Emperor Constantine’s official tolerance of the religion in 313, and its official structure came with it. Each bishop governed a territory or diocese from the seat or cathedral. The first bishops were the twelve apostles; Saint Peter was the first bishop of Rome, a position of leadership and authority now held by the Pope.

Shortly after the Romans withdrew from Britain in the 5th century, the pagan Anglo-Saxons invaded, but their geographic occupation wasn’t complete; the Western parts of the country remained Christian. Elsewhere, the bishops and their churches vanished, and we entered what used to be known as the Dark Ages, now called the Early Middle Ages.

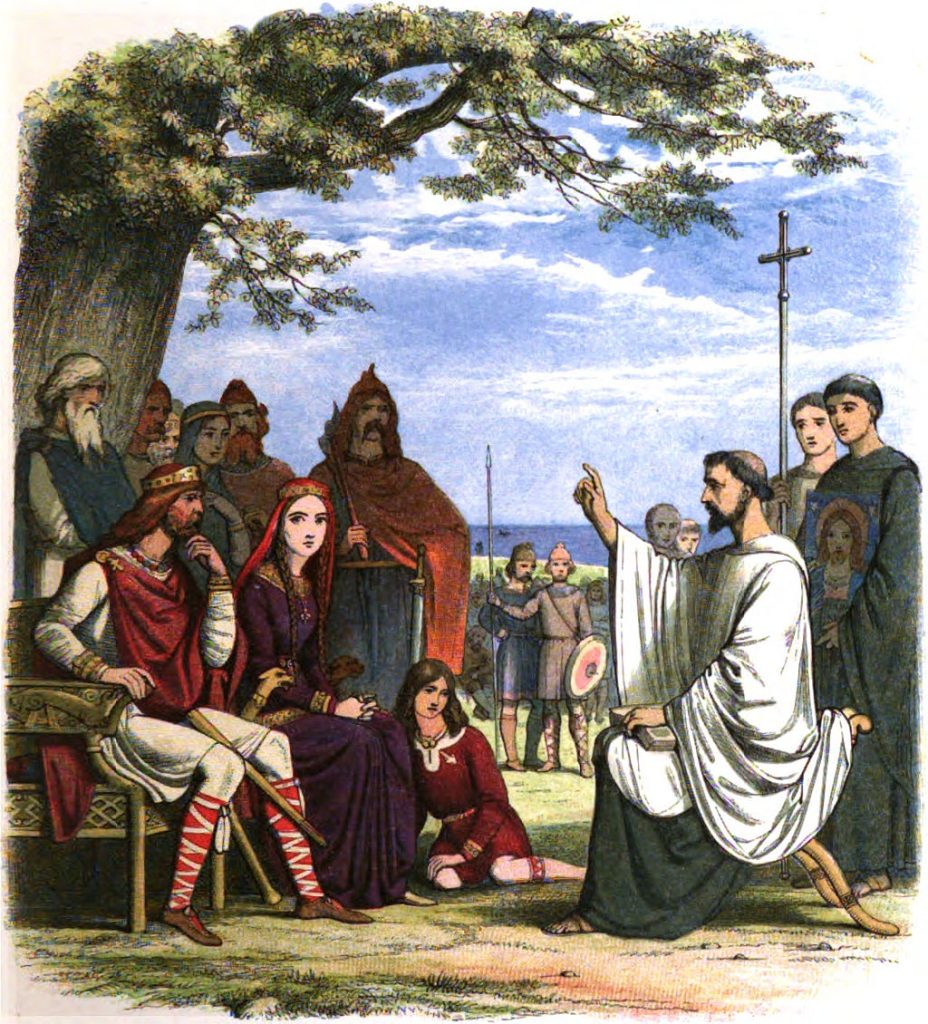

But by 597, Christianity was on the upswing again. Pope Gregory sent Augustine with a group of Benedictine monks to England to rally the troops. Augustine formed monasteries at Canterbury and Rochester, and throughout the seventh century, Christianity was re-established in Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, adding bishops and their cathedrals.

Norse raiders created a great deal of havoc, however, starting in 793 on the coast of Northumberland, destroying the Lindisfarne monastery and making off with anything of value.

Over the next two centuries, the Vikings sacked and pillaged, overthrowing much of the country; Durham, Canterbury, Rochester and Winchester, among others, suffered horribly.

Gradually, over time, the Vikings were integrated. The influence of the kings of Wessex expanded, beginning with King Alfred (891-99); by the time King Aethelstan came to the throne (924-39), England was effectively united, and the Christian church organization had taken hold once more.

When the Normans invaded in 1066, England had 15 cathedrals, with archbishops at Canterbury and York and thirteen other bishops. The Norman Conquest unleashed an entirely new era for England and its cathedrals, with a building program of epic proportions. By the end of the 12th century, the Anglo-Saxon cathedrals had been torn down and replaced with massive Romanesque structures, most protected by an adjacent castle. This sustained construction endeavour created an abundance of supportive industry—towns sprang up, complete with butchers, bakers and candlestick makers to supply the constructors.

Building and renovating continued unabated until the 16th century, despite the Crusades, the Hundred Years War with France, and the Black Death. Along the way, structural innovations, most notably the pointed arch, saw the favoured Norman or Romanesque style gradually give way to three periods of Gothic Architecture: Early (1170-1250), Decorated (1250-1350), and Perpendicular (1350-1530).

All this building was expensive. Very expensive. The solution? The growing popularity of saints and the healing power of their mortal remains—saints’ relics attracted pilgrims (and donations)! So a whole new crop of saints was produced on the scantest evidence of a miracle, the candidate nearly always being a recently deceased bishop of the relevant diocese. Coincidence? I think not.

But these pilgrims took up a lot of room, and the clergy didn’t wish to mingle with them (or the townsfolk, for that matter). This led to a new stage of cathedral construction—the expanded east end, with its separate presbytery for the clergy and a chapel for the saint. The townsfolk could use the nave, and the clergy would use their presbytery with its high altar.

Polarization and social tension are as old as time. Though some cathedrals were secular, most were attached to a monastery and those operated under a different authoritative structure. Bishops of the cathedrals warred with abbots of the nearby monastery over jurisdiction, particularly at Rochester and Durham. Townspeople were annoyed with the wealth and arrogance of both institutions and frustrated with the hoards of visiting pilgrims, donating ever more to the cathedral coffers.

Meanwhile, the Reformation was brewing in Europe. Martin Luther questioned the role of the Catholic Church, particularly in acting as an intermediary between parishioners and God. Moreover, moral laxity had set in throughout the clergy, from bishop to the lowliest deacon.

Then along came Henry VIII and his Great Matter. In 1533, at the behest of Henry VIII, infuriated with Pope Clement VII’s refusal to grant him an annulment of his 24-year marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Parliament passed the Act of Restraint of Appeals, making England independent of all foreign authority, including the Pope. Thomas Cranmer formally and obligingly granted the annulment and became the Archbishop of Canterbury as a reward. The Pope retaliated by excommunicating Henry, which was to prove very expensive for Rome and devastating for the monastic community in England.

In 1534, Henry countered: Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, making Henry VIII the Head of the new Church of England. The Dissolution of the Monasteries followed in 1536, and with breathtaking speed, the monastic way of life was terminated. By 1539, not a single religious house remained in England.

To a great extent, the cathedrals escaped unscathed, though some dioceses were rearranged. Nevertheless, the monastic buildings were largely destroyed, valuable assets seized, and clergy pensioned off or turned out to find their way in a vastly altered world.

The actual religious ritual got an overhaul, but in Henry’s time, it was fairly mild. The saints and their relics, however, got a very rough ride. Henry VIII was determined to eliminate any chance of the monasteries refinancing themselves. Thomas a Becket’s shrine at Canterbury was obliterated, no doubt payback for the humiliation of Henry II.

The next few centuries were ruinous for the fabric of the cathedrals and the lives of the people, subject to rapidly changing religious doctrine. Henry’s son, Edward VI, acceded in 1547 with more fervent Protestantism. Mary I, a devout Catholic, followed Edward VI a mere six years later; she slammed the whole process into reverse with the Counterreformation. Heads rolled, and heretics burned through both reigns until Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558. A Protestant, her policy of “not making windows into mens’ souls” provided a much-desired respite from the religious factionalism, though things did get a bit testy upon the discovery (true or trumped up) of the Catholic plotting of her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots.

The English Civil War (1642-1651) brought further turmoil to our cathedrals. Parliament abolished bishops in 1646, and when Charles I was beheaded three years later, a new law ended cathedrals as organizations, dissolving all titles and posts of deans, churches, tithes, canons, and prebendaries. Their lands, churches, sources of income, and records were all confiscated. Oliver Cromwell ruled as Lord Protector from 1653 to 1658, unleashing unholy destruction of anything considered “popish”, beheading statues, and smashing stained glass. Nevertheless, the denuded cathedrals survived, holding services for plain preaching. It must have been a jolly time—yikes!

The Restoration of the Monarchy in 1658 brought Charles II to the throne and the re-establishment of the Church of England. Gradually the cathedrals regained all their former possessions—lands, houses and political influence. Severe damage was repaired, altars and screens restored, and treasures and glass came out of hiding.

I want to say it all ended happily at this point, but Charles II was a man of his time—he had a dozen illegitimate children but no heir. When he was succeeded by his brother James, the discovery of James’s conversion to Catholicism set off a paroxysm in government circles; no one wanted another Civil War. James was deposed, and his daughter Mary was invited to rule jointly with her copper-bottom Protestant husband, William of Orange, ushering in The Glorious Revolution and the reign known as William and Mary. They were succeeded by Mary’s sister Anne, who, despite 18 pregnancies, left no heirs. Thus ended the Stuart Dynasty.

And so, in 1714, we began the Georgian Period, the first of whom was Elector George of Hanover. Though a delightful era in many ways, inspiring many a Regency romance, it was not kind to our cathedrals. James Wyatt, an English architect and a rival of Robert Adam in the neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles, despised anything Gothic. Any cathedral he touched was subject to renovations diplomatically described as “heavy handed”. More medieval stained glass was destroyed during his tenure than Cromwell’s. Fortunately for our cathedrals, he was easily distracted and somewhat erratic, quickly losing interest in projects for which he was responsible. His death in 1813 was followed fairly rapidly by Queen Victoria’s rise to the throne in 1837, just in time to rescue the cathedrals, which were in a parlous state by then.

When the bishops regained their positions (and possessions) at the Restoration in 1658, they wielded a virtual veto on reform; after several centuries of turmoil, resistance to change was understandable. But stability moved to rigidity and foundered in ossification. By the 19th century, a thorough reform of its Church and State was called for. The drastic Cathedral Act of 1840 ended sinecures, pruned patronages, and centralized revenues under the ecclesiastical commissioners. Cathedral chapters saw a massive (and much needed) £300,000 transferred annually to parish churches in the industrial cities—the less affluent parts of the country. This was the most drastic reorganization since the Reformation, creating new dioceses, bishops and cathedrals.

Architectural revival followed. England’s cathedrals were pulled back from the precipice of disaster. This new age of Restoration evoked the “ideal” cathedral — Gothic — which was to recreate rather than conserve its battered remnants. Enter George Gilbert Scott and John Loughborough Pearson, architects who were given nearly free rein to recreate cathedrals in the Gothic style, unleashing the battle of the Decorated vs the Perpendicular. Stained glass entered a new phase of creativity with craftsmen such as Augustus Pugin, Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris and Charles Eamer Kempe.

The 20th century gave us eight new cathedrals, with twelve more added in the 21st century. Bombing during the Second World War wrought severe damage to some, particularly to Coventry Cathedral, which was rebuilt entirely in a controversial modern style, to the dismay of many.

Though religious observance continues to decline, English Anglican cathedrals continue to thrive, many returning to their medieval roots, with their naves serving as multi-purpose facilities for community events, providing space for large functions, and ancillary buildings such as chapter houses serving as venues for smaller events. Tourist traffic abounds, attracting more than 10 million visits per year.

In the words of Monty Python—they’re not dead yet! Fifteen centuries later, they’re still going strong.