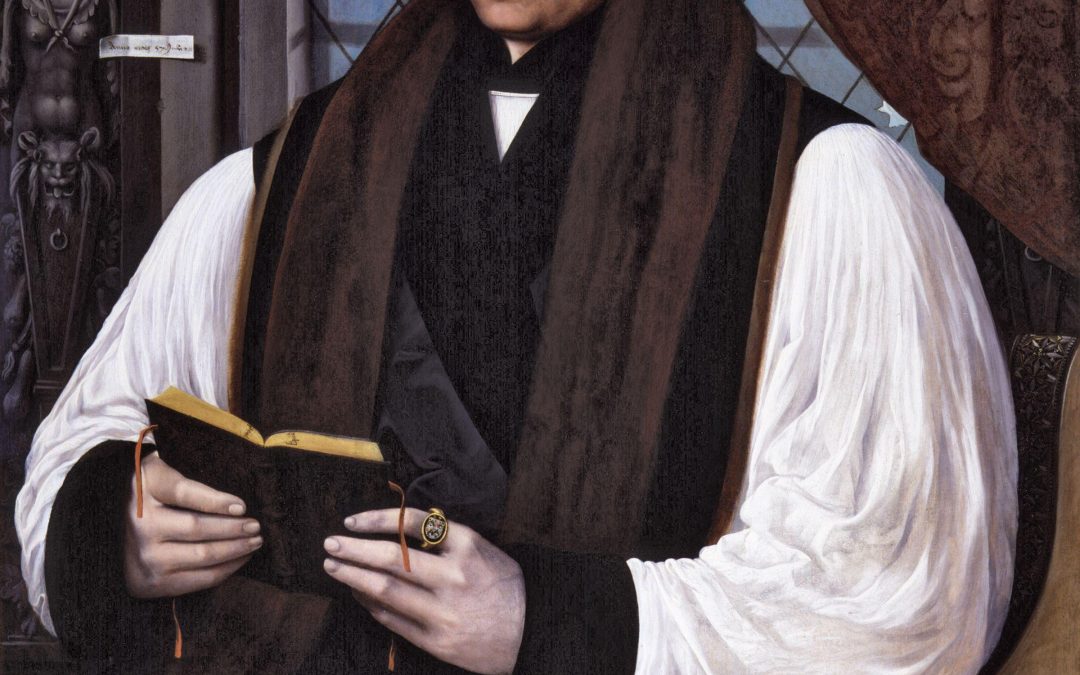

Viewing the behaviour of Thomas #4, Cranmer, from a distance of 500+ years, it’s difficult to determine if he was wily or wishy-washy—perhaps both.

As part of the double act with Thomas #3 Cromwell, Cranmer played a vital role in ending Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Cranmer was the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury and the only one of the Tetrad of Thomases who outlived Henry VIII. He went on to serve under young King Edward VI and finally came a cropper when Bloody Mary rose to the throne upon the death of her younger brother.

Cranmer was born in July of 1489 and, as a younger son, was slated to join the church. He began studying at Cambridge in 1503 and, by 1510, was pursuing a fellowship at Jesus College, established in 1496 on the site of the twelfth-century Benedictine nunnery of St Mary and St Radegund by the Bishop of Ely, John Alcock. Somewhat oddly, Cranmer was forced to vacate his fellowship upon marrying a relative of his landlady—the first “wobble”, as it were.

Shortly after, Cranmer’s wife died in childbirth, and the college restored his fellowship. He resumed his studies in earnest, was ordained and six years later received his Doctor of Divinity degree; meanwhile, he was meeting regularly with scholars to discuss Martin Luther’s work and later became a prominent figure in the group leading the English Reformation.

Cranmer might have remained an obscure academic were it not for the King’s Great Matter, into which he was drawn by a matter of chance (good or bad, you can decide). Since 1527, King Henry VIII had been pursuing an annulment from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

In August of 1529, a deadly plague known as the “sweating sickness” had concentrated in Cambridge, and Cranmer had decamped with two of his pupils to their father’s house at Waltham in Essex. The King happened to be in the immediate neighbourhood with two of his chief councillors, Stephen Gardiner and Edward Fox, who met Cranmer in those lodgings soon afterwards. Inevitably, talk turned to Henry’s dilemma, and soon Cranmer accepted a commission to write a persuasive treatise in the King’s interest, basing it on arguments from Scripture, the Fathers, and the decrees of general councils.

Enter Anne Boleyn, Henry’s current love interest and soon-to-be second wife. Cranmer accepted her father’s hospitality and resided at Durham Place while undertaking his work. Before long, Cranmer had been appointed archdeacon of Taunton and became one of the king’s chaplains. When the treatise was finished, it was argued before the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, who endorsed it. But Cranmer had already been redeployed to plead the cause before more august powers: Rome. to which a committee was dispatched in 1530. Here, the entourage was received with courtesy and dithering from the Pope, who knew on which side his bread was buttered. Catherine of Aragon’s nephew was Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and the Pope would not risk upsetting him.

Cranmer seemed to live a life of travel after that. In 1532 he was sent to Germany, officially as ambassador to the emperor Charles V (who clearly had to be won over). Here Cranmer met Andreas Osiander, of a theological position midway between Luther and the old Catholic orthodoxy, which greatly appealed to Cranmer (and Henry VIII, for that matter). Cranmer also met Osiander’s niece Margaret, and in defiance of his priest’s orders, he married her in 1532. Wobble #2—priest marrying. A no-no.

Meanwhile, William Warham, the aged Archbishop of Canterbury, died in August 1532. Who was to replace him? Thomas #3, Cromwell was busy drafting the Act Against Appeals to Rome, so the King’s Great Matter was coming to a head, not least because Anne Boleyn was pregnant. Despite his lack of stature or experience, Cranmer was tapped as Warham’s successor. No sooner was the mitre on his head than he quickly annulled the King’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon and pronounced the marriage to Anne Boleyn valid.

But things didn’t work out so well for that marriage. Anne Boleyn produced a daughter, the future Queen Elizabeth, in September of 1533, much to Henry’s disappointment. Several miscarriages followed, and Henry grew impatient. By 1536, his eye had lighted on Jane Seymour, and Anne’s days were numbered. Two divorces would be implausible; better come up with something else.

Anne (and five men, including her brother and father) were executed on May 19, 1536, on dubious evidence of Anne’s alleged adultery.

Jane Seymour became wife #3 on May 30 but inconveniently died in childbirth shortly after that, though Henry did finally get his much-desired son, the future King Edward VI.

Cranmer remained elastically helpful. He invalidated Henry’s marriage to wife #4, Anne of Cleves, in 1540, and 1542 saw his prominent participation in the trial leading to wife #5, Catherine Howard’s execution for treasonable adultery.

As Archbishop of Canterbury, Cranmer was ineluctably drawn into the reconstruction of the Church. Personally, he leaned more toward reform than could find a scope with the King, who had little appetite for change in doctrine. The Cranmer/Cromwell double act published an English Bible, and in 1539 its use became compulsory.

Cranmer’s drift to Protestantism continued; By 1536, he was identified as one of the leading proponents, and by the time Henry VIII died in 1547 (married to his sixth wife, Catherine Parr), he had composed a litany for the Reformed church in England, one of his most recognized works, and still in use today, and had jettisoned his belief in transubstantiation.

The Act of Six Articles, published in 1539, took issue with those advocating marriage of the clergy and those denying transubstantiation, both problematic for the married Cranmer. Then came Cromwell’s fall from grace in 1540. Thus far, Cranmer had been protected by Henry VIII, who found him trustworthy and singularly lacking in ambition. Indeed, Cranmer’s rise had been by happenstance, though certainly aided by his intellectual rigour coupled with pliable conduct.

Upon Henry’s death and the accession of Edward VI, Cranmer’s star rose still higher. The new king was nine years old; Henry had appointed a council to rule until he attained his majority, but wily manoeuvres by the nakedly ambitious Edward Seymour, Edward’s uncle, saw him assume the position of guardian and thus took to himself all the powers of a king. Seymour made himself the Duke of Somerset, unleashing his desire to fully transform the Church of England into a Protestant church.

Somerset was ousted by John Dudley (later the Duke of Northumberland) in 1549, and he was even more extreme in his definition of Reform.

Cranmer went along for the ride. In 1547 he oversaw the publication of the moderately Protestant Book of Homilies, directing the preaching of the clergy, followed by a more outspokenly Protestant version in 1552. Cranmer’s Forty-two Articles appeared in 1553, defining the dogmatic position of the Church of England on current religious disputes. Everyone—clergy, schoolteachers, and university degree candidates—was forced to subscribe to the articles, later reduced to 39 and officially accepted by the Anglican church. Cranmer dominated and guided the religious revolution of Edward Vi’s reign through his diligence and ecclesiastic authority. Doctrine, ritual, and law of the Church of England were formed under Cranmer and remain today.

But—his star was soon to fall. He got himself involved in politics and picked the wrong horse.

Edward VI contracted tuberculosis, and his condition declined rapidly. By July 1533, John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland, was plotting to oust the avowed Catholic Princess Mary (daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon) from the succession. In her place as Queen of England was to be Dudley’s daughter-in-law, the great-niece of Henry, Lady Jane Grey.

The plan went pear-shaped, to say the least. Although proclaimed queen, the hapless pawn Lady Jane Grey, age 17, was deposed nine days later and executed. Mary I, having waited many a long year, in and out of favour with her father, Henry VIII, acceded to the throne and unleashed the Counter-Reformation.

Cranmer was charged with treason in November 1553 and imprisoned. Treason was a convenient charge, but that was not really what this was all about. Mary was incandescent with rage at Cranmer’s long-standing role in promoting Protestantism, and he would suffer for it. It took some time to get Parliament to repeal Henry VIII and Edward VI’s laws and reintroduce the burning of heretics. By September 1555, Cranmer began a lengthy trial, whose conclusion was foregone. On February 14, 1556, he was stripped of all his ecclesiastical offices and handed over to the state.

With legal ducks lined up, Cranmer’s woes really began. Mary was determined that his humiliation be complete. Burning was the least of it—he needed to recant and renounce his “errors” in public. So a not-so-subtle program of breaking Cranmer down began. First, he was transferred from prison to more pleasant surroundings. At the same time, government agents delicately planted doubts, and indeed, Cranmer signed five so-called recantations, of which the first four merely recorded his consistent belief that what monarch and Parliament had decreed must be obeyed by all Englishmen. This logically led him to accept the validity of Counter-Reformation. The sixth recantation of his whole religious development came shortly after.

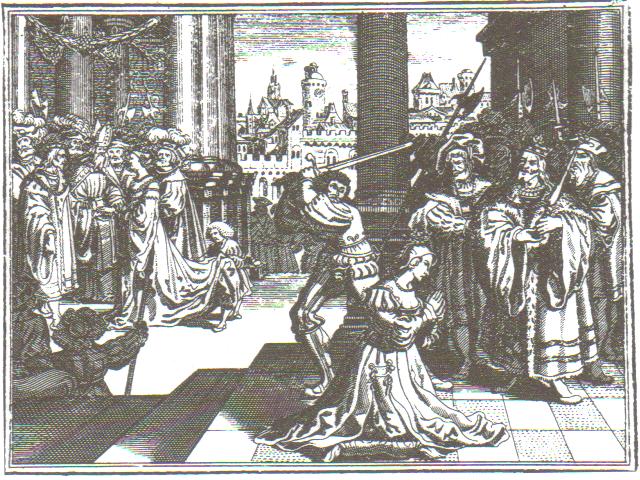

None of this saved Cranmer. Though Mary and her government hoped that publishing Cranmer’s recantations would destroy Protestantism in England, they were equally determined that Cranmer should suffer a gruesome execution. So on March 21, 1556, Cranmer was taken out to be burned.

But, in an object lesson in knowing when to quit, Cranmer’s defiance roared into action. Tied to the stake, with nothing to lose and his dignity to gain, he appalled his enemies by disavowing his recantation and emphatically reasserting that the Pope’s power was null and void and that transubstantiation was a load of codswallop.

At a stroke, Cranmer demolished the government propaganda and reignited the determination of the surviving Reformers. He held his right hand—which “had offended” by signing the false recantations—into the flame until it was consumed.

Wily or wishy-washy? Not at the end; he wasn’t.