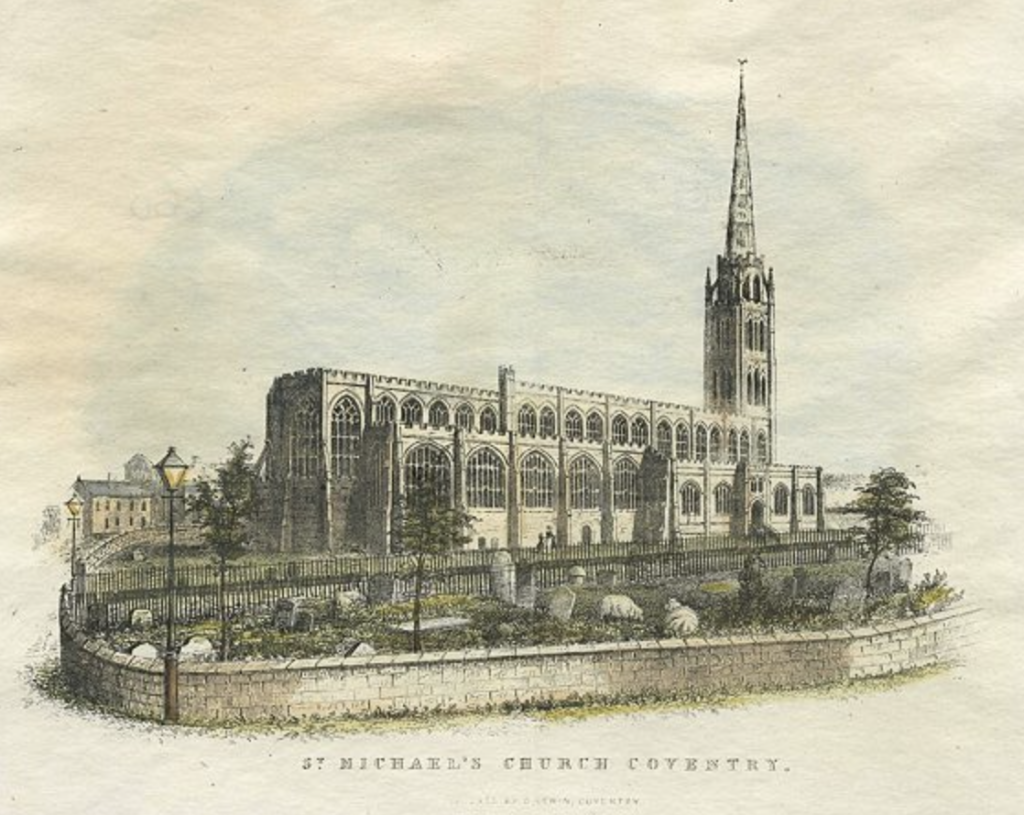

The ruins of the Cathedral Church of St Michael are a haunting site. Built between the late 14th and early 15th centuries, a shell is all that remains following the massive attack by German bombers on the night of November 14, 1940.

Originally one of the largest parish churches in England, it became the Cathedral of the Diocese of Coventry only in 1918.

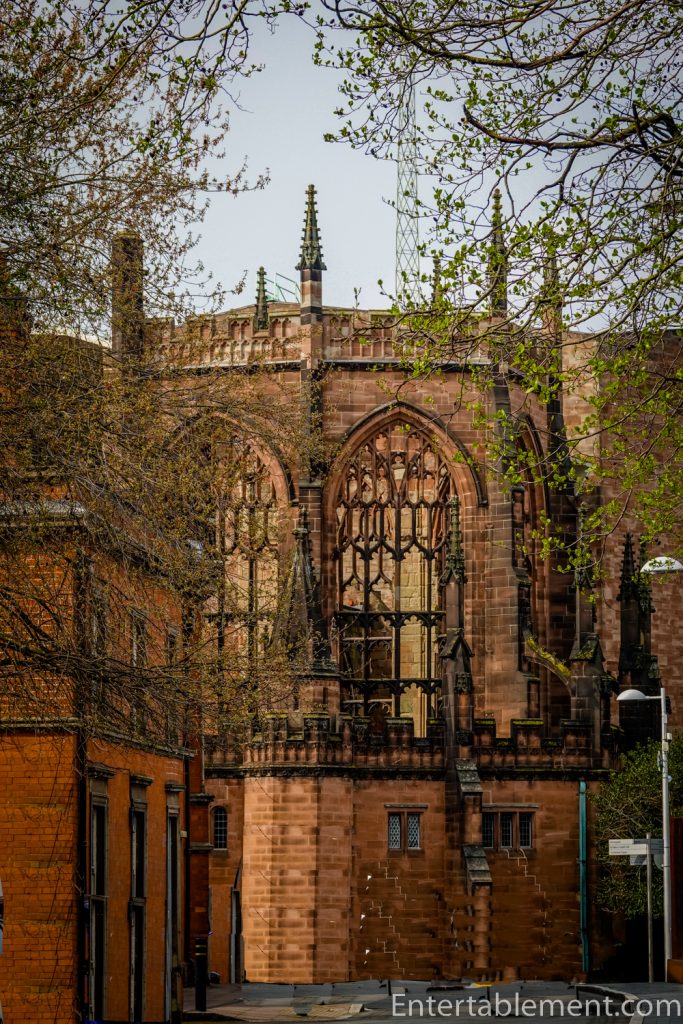

The magnificent west tower and spire were built between 1374 and 1450. At 295 feet, it is the third tallest of any English cathedral—only Salisbury and Norwich reach higher. It still dominates the city centre, surviving the bombing that destroyed the church’s interior.

St. Michael’s has a fascinating history. It replaced St Mary’s Priory and Cathedral, founded in the 12th century and with the dubious distinction of being the only Cathedral church wholly destroyed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The seat of the diocese was transferred to Lichfield in 1539 and became the Diocese of Lichfield and Coventry. Thus Coventry New Cathedral, appended to the ruins of St. Michael’s, is Coventry’s third Cathedral building.

You may be gathering that Coventry cathedrals have had a very rough time!

The Old Coventry Cathedral was Perpendicular Gothic in style, with an open nave, allowing a clear sight line from the west end of the church right through to the high altar in the east. The flat wooden roof hints at the vast space across the nave, encompassing a whole aisle on each side. Its open-plan design looks modern, making it even more puzzling that when it came time to rebuild after the Blitz, no consideration seemed to restore it, but a jarring addition was appended to the ruins.

This photo is taken from the west end of the Old Cathedral, showing an additional chapel on the north aisle and a large southern transept.

At the start of WWII, it was clear that Coventry would be the target of the bombing. The city’s factories made engines, aeroplanes and munitions vital to Britain’s war effort.

So in the fall of 1940, the Cathedral Provost, the Very Reverend Richard Howard, established the Coventry Cathedral Guard, a group of a dozen men who took shifts in groups of four to watch over the Cathedral.

They were put to the test on the night of October 14, 1940, when an incendiary bomb broke through the roof.

It was difficult to quickly remove the ancient lead sheeting on the roof before it melted into the wooden pews below. More than £1,000 of damage was sustained before the fire was put out, and that was only a foretaste of what was to come.

A month later, on November 14, 1940, another raid started at 7 pm. The Reverend Howard and three volunteers—stonemason Jock Forbes, Mr Eaton and Mr Wright, were waiting and watching on the roof of the nave.

A wave of high-explosive bombs hit the city. Their targets were the water, electricity and telephone systems. A barrage of incendiary bombs designed to create sustained fires followed.

An hour later, the Cathedral had taken direct hits on the roofs of the chancel, the nave, the south aisle and the east end.

The four men deployed buckets of sand over the bomb on the chancel and managed to get it out of the building, but the bomb in the nave had set the wooden pews alight. More sand managed to extinguish that fire.

The ceiling above the organ was in flames. The men deployed stirrup pumps to douse the fire, but the smoking lead was difficult to shift.

Meanwhile, yet another bomb fell on the Cappers’ Chapel and set the beams alight, pouring fire onto the wooden chairs beneath. Another shower of incendiaries fell. Supplies of water and sand were running out.

When the Solihull Fire Brigade arrived at the Cathedral at 9.30 pm, it was too late to save the building.

The raid had devastated the entire city. Over 500 people had been killed; many more were seriously injured.

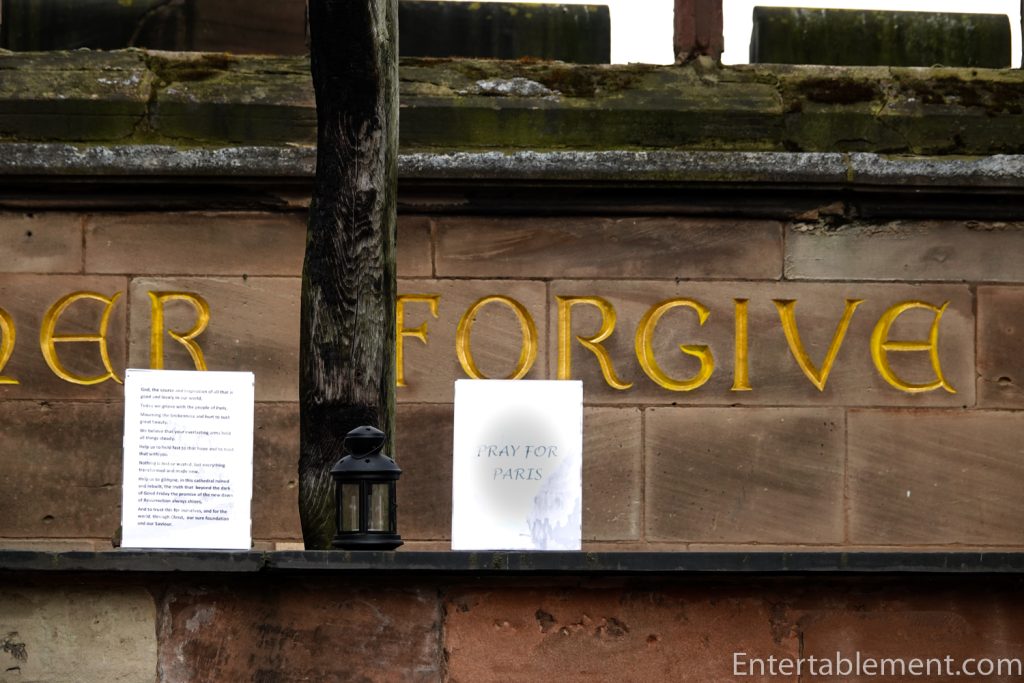

Images of the destruction shocked the British public, but Reverend Howard was determined not to encourage calls for revenge. Jock Forbes, St Michael’s stonemason, tied two charred beams into a cross and placed it near the ruined altar. The words “Father, forgive” were written close by on the walls.

We visited Coventry in April 2019, just after Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris had been devastated by its own fire. It was heartbreaking to think that another treasured medieval Cathedral had suffered the same destruction (though by accident, not design, in Paris’ case).

When WWII drew to a close, the Cathedral’s leaders decided to preserve the ruins as a memorial to the horror and waste of war.

Forbes’ cross can still be seen in the new Cathedral today.

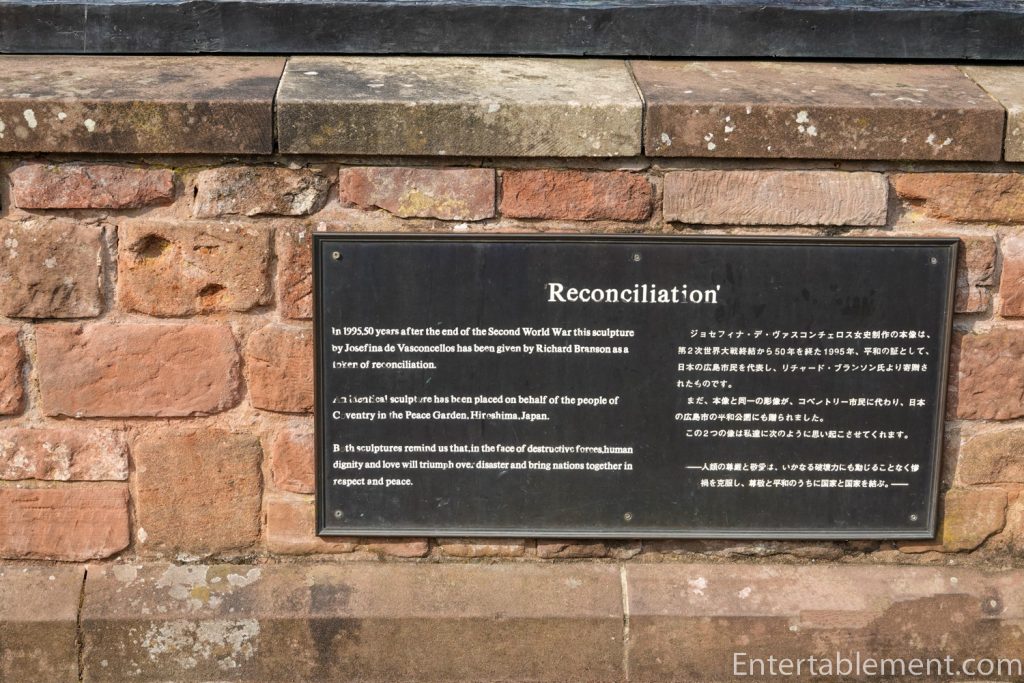

The statue Reconciliation by Josefina de Vasconcellos sits in the ruins of the Old Cathedral.

It was initially entitled Reunion when it was made in 1977 and presented to the University of Bradford’s Peace Studies department.

After repairs and renaming, a bronze cast of the statue was presented to the Cathedral in 1995, the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II.

The bronze effigy and tomb of Coventry’s first bishop, Huyshe Yeatman-Biggs, miraculously survived and remain in place.

I’m not a fan of the old/new blended construction.

While I fully appreciate acknowledging the horrors of war, leaving the old Cathedral in ruins seems to reflect the desire of modern architects to make their mark with a new project rather than a sign of respect.

And I suspect Bishop Yeatman-Biggs would rather have seen his Cathedral restored and his tomb safely under a solid roof.

The vast majority of the Cathedral’s medieval glass had been packed up and stored in crates at the start of the war in anticipation of the destruction to come.

The architect and designers went through the boxes and chose pieces to be included in the very modern windows in the New Cathedral, so now priceless medieval stained glass sits discarded, like a jigsaw puzzle with vital pieces missing. Why could they not have just returned it to where it belonged?

Rest in Peace, Coventry Cathedral.