While York Minster is architecturally stunning, it has also always been politically noteworthy. In 1042, its Archbishop Eldread Edward the Confessor was succeeded by Harold Godwinson in 1066. Later that same year, Eldread was called to Westminster Abbey to crown William the Conqueror.

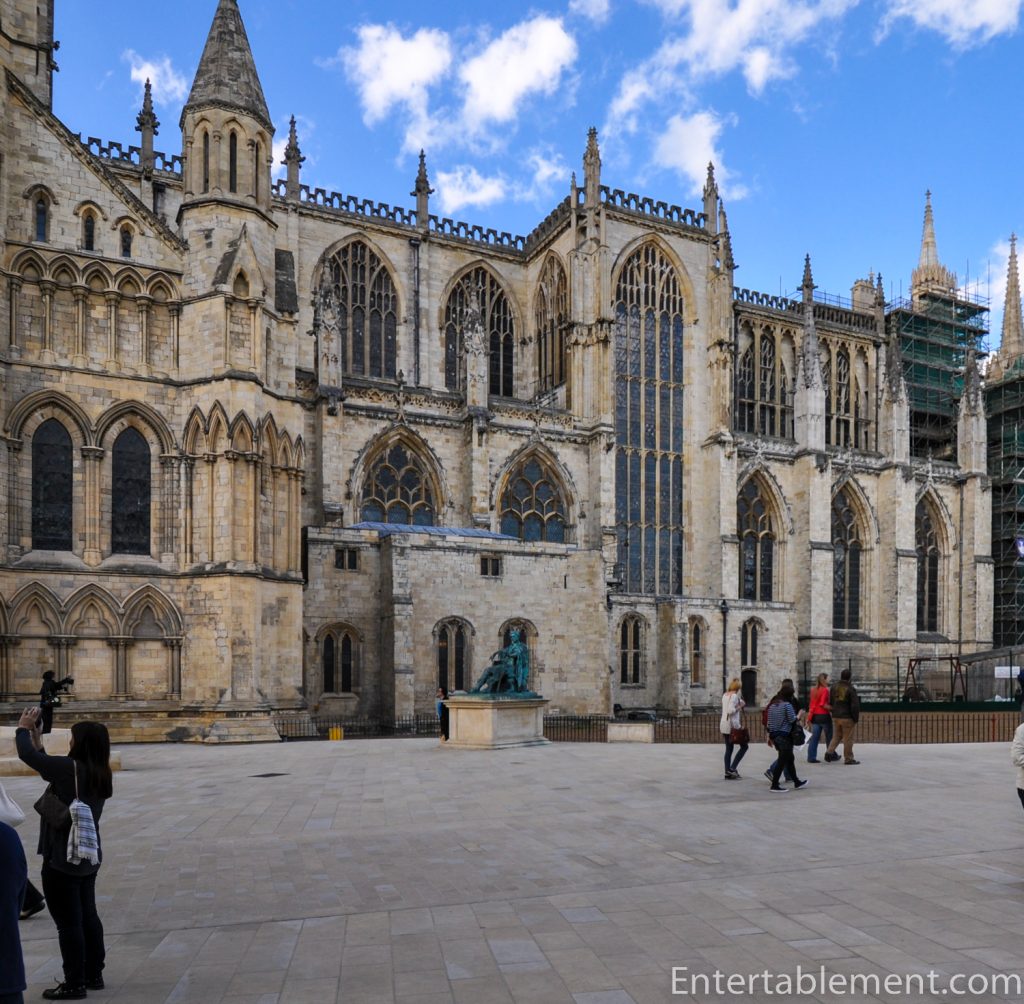

The building is magnificent, soaring above the city and its medieval walls.

Today, York Minster is the seat of the Archbishop of York, who ranks only behind the Archbishop of Canterbury in the ecclesiastical hierarchy of the Church of England.

Roman Christians were in York as early as 180 AD. We know that three bishops from England were present at the council of Arles in 314: Restitus of what we now call London, Adelfius (of either Lincoln or Colchester) and Eborius of York.

The Romans packed up and left Britain in 410. Though Christianity carried on in pockets, the pagan Anglo-Saxons had the religious upper hand until 595 when Pope Gregory sent St Augustine on a mission to convert them to Christianity.

When pagan Edwin, King of Northumbria, became betrothed to Ethelburga, daughter of the Christian king Ethelbert of Kent, a condition of the match was that Edwin convert to Christianity. Paulinus, sent to support Augustine in his efforts, baptized Edwin and was rewarded with elevation to Bishop of York. York is a Minster; it was never a monastery.

A Norman church was built on the site in the 1080s under Thomas of Bayeux. Funding came from the diocese, whose lands included sixty-five monasteries in Northern England south of Durham. Revenues were enhanced in 1227 when Bishop William Fitzherbert, who had been poisoned in 1154, was finally canonized, and a shrine was built.

Walter de Gray, who became Archbishop in 1215, was eager to build a Gothic cathedral grand enough to equal Canterbury, the gold standard of the time.

With all its overwhelmingly grand presence, it is startling to realize the building sits on a mere 5 feet of foundation, forcing external appearance to take a back seat to the need for stability. The result is buttressed galore, cramping the proportion of windows to walls.

The large central tower was considered too delicate to support a spire; interest was added through the pairs of long bell openings on each side. The south transept, formerly the main entrance, is thought to be a mishmash of gothic exuberance with four layers of lancets and three triangular niches over the door.

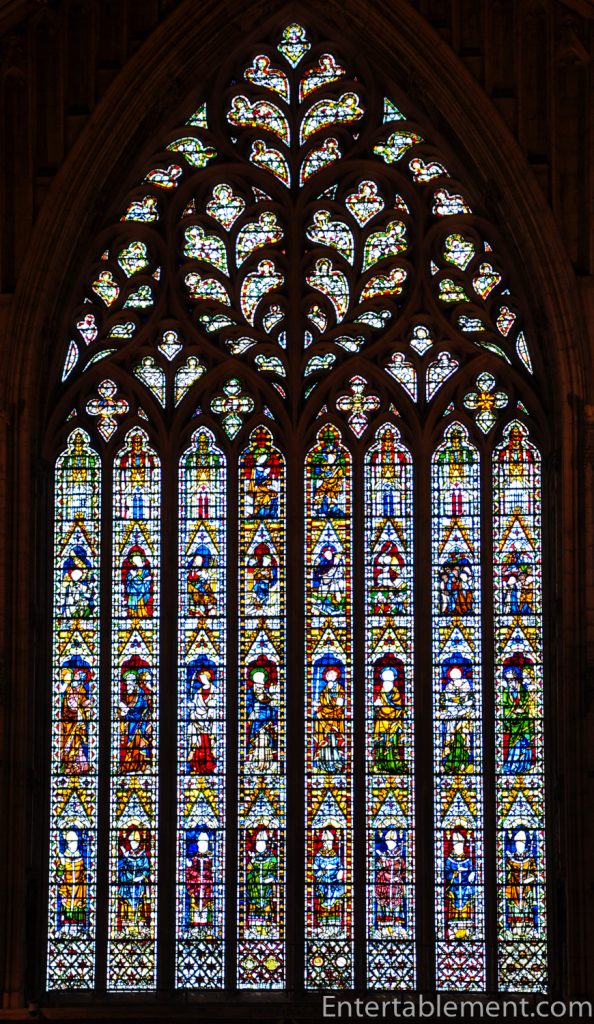

The West Front’s piece de resistance is its magnificent Heart of Yorkshire window. Let’s step inside to better admire its stained glass.

It was completed in 1339; eight slender lancets rise to an oval pierced by another oval, creating the famous heart.

It is almost a guidebook to the hierarchy of the church. Bishops are depicted on the bottom layer and saints above. Events of the bible are depicted in the third row from the bottom, topped with the Coronation of the Virgin in the fourth. All we know of the people who created it are their names: Master Ivo was the craftsman who built the tracery; Master Robert created the glass.

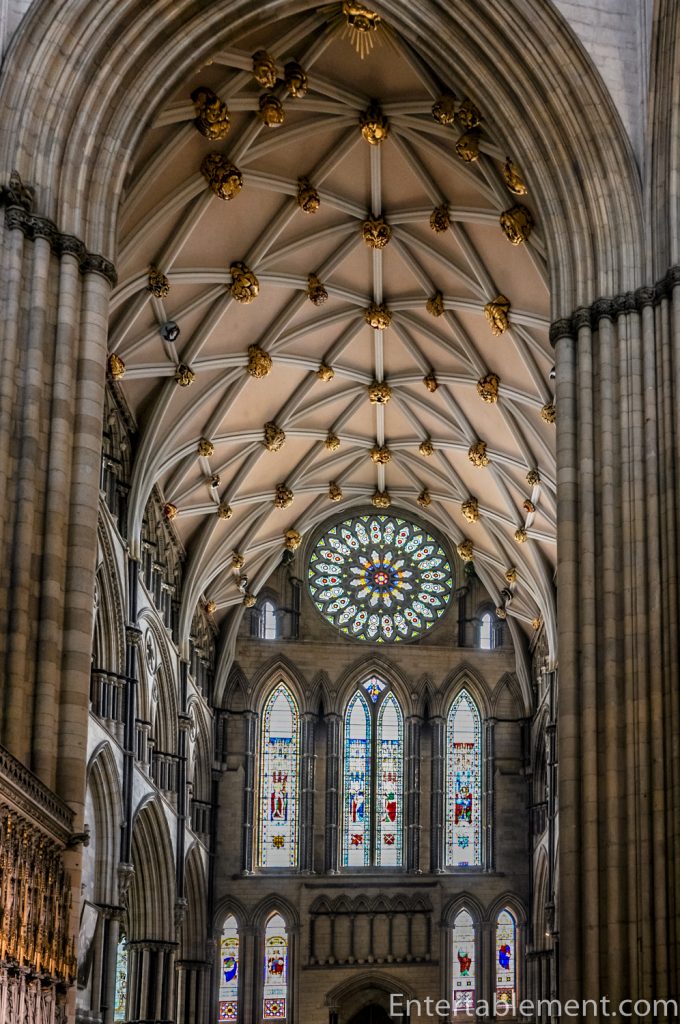

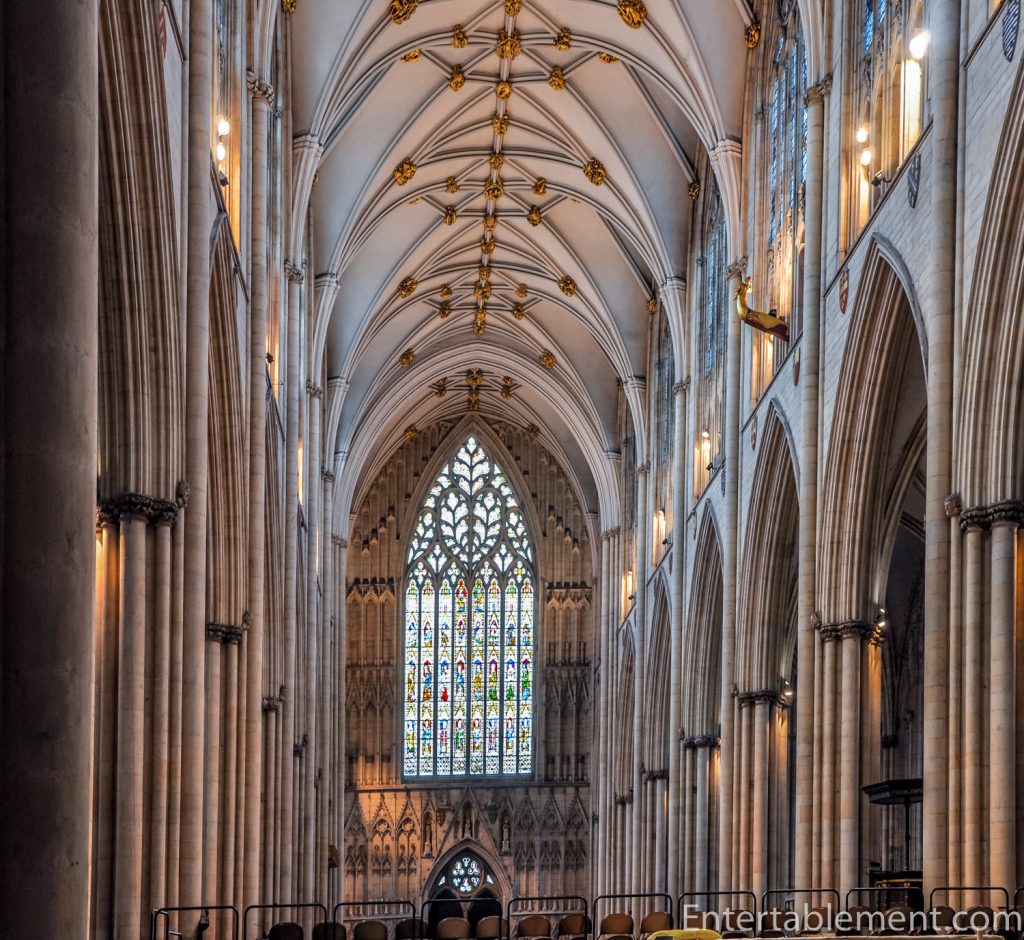

The nave is the largest interior volume in medieval England. It dates from the mid-14th century, a high point for Decorated Gothic.

Each bay soars upward within single shafts of Purbeck marble, rising from floor to ceiling. Within each section, one ground-level lancet arch gives rise to four above it at the triforium on the second level and five lancet arches of the clerestory at the top.

Each pair of arches in the triforium are tucked under a blind lancet arch snuggled into a rounded facade, edged in lacy trim.

The nave is very wide relative to its height, necessitating a wooden, rather than a stone vault, recreated during the Victorian era following a fire in 1840.

The bosses were replicated exactly, with the exception of one.

Note below that Mary is bottle-feeding Jesus—the prudish Victorians refused to allow depictions of breastfeeding in the Minster. How times have changed!

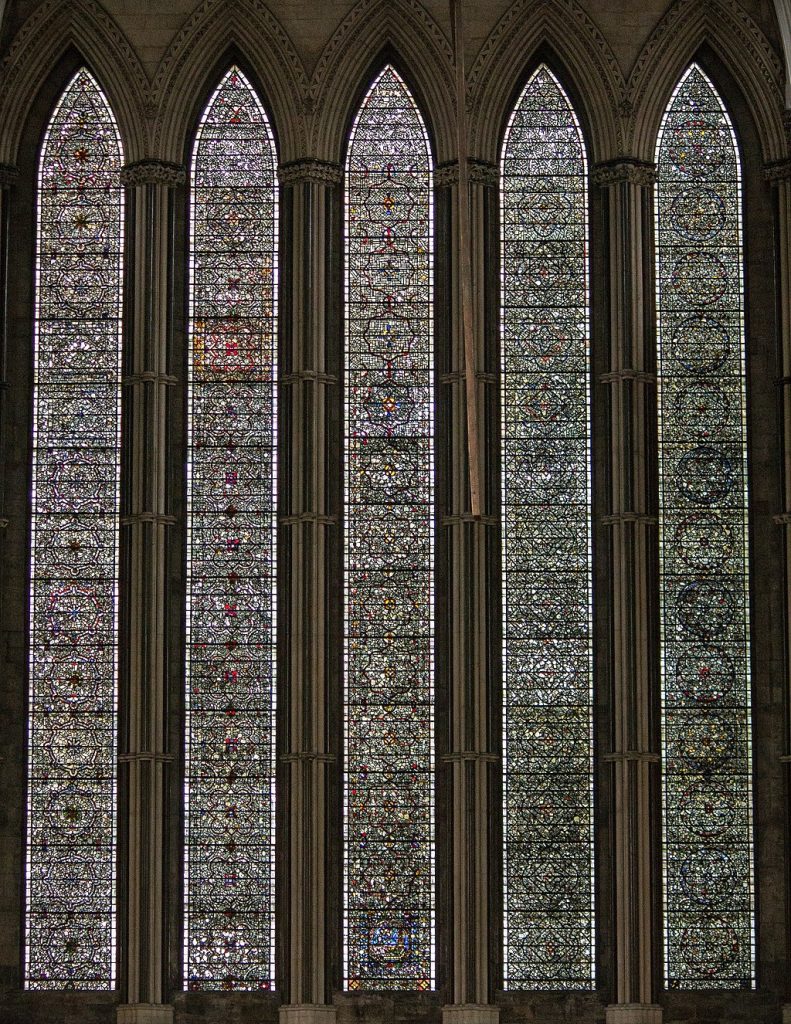

Let’s head now to the transepts, which were begun in 1220 and completed in 1250. In the North Transept, we find the Five Sisters Window, dating from 1255. At 53 feet high, the lancets are the tallest in England. The original glass comprises 100,000 tiny pieces of grey, touched with dots of colour. At the bottom of the central panel is a tiny depiction of Daniel in the Lion’s Den, included from an earlier Norman window. Otherwise, the pattern is abstract.

The South Transept contains a rose window. Originally, it was called the Marigold window (no, not you, Marigold).

But in the 1500s, red and white glass roses were inserted, honouring the union of Lancaster and York.

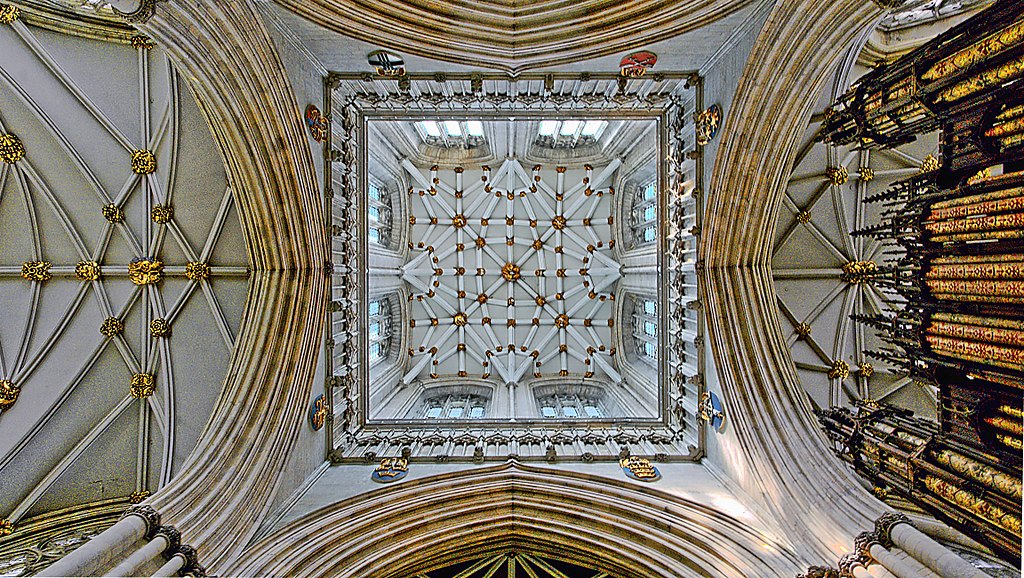

The ceiling looks elegantly quilted, like a rectangular fondant-coated wedding cake.

I’m always thrilled when we get to the crossing.

Look up into the tower in the centre. To me, it’s the heartbeat of the church.

Below the crossing is the 14th-century pulpitum. It glorifies the house of Lancaster, with which the Minister was always heavily aligned, despite being in York. During the War of the Roses, Northern England was caught between two fires, so to speak. The powerful northern Plantagenet families of Neville, Percy, Mowbray, Clifford and Hastings offered support against Scottish incursions to the North even while fending off the English York faction to the south.

It’s difficult to detect, but it’s asymmetrical—the door is off-centre. It holds fifteen statues. You can count seven on the left (see above) and eight on the right (see below). They are monarchs William I to Henry V; the latter’s early demise necessitated the quick addition of Henry VI, throwing off the balance. The political aspect of this screen was further heightened when the same Henry VI was murdered, prompting its removal to accommodate his cult following, eager to venerate a saint that never did get canonized. It was later replaced by the Victorians during their restoration. (As an aside, Henry VII also anticipated Henry VI’s impending sainthood and built an enormous chapel at Westminster Abbey in preparation, only to have the chapel form his own mausoleum.)

It took quite a while for the Norman choir to be renovated—it wasn’t rebuilt until 1360; by then, Gothic had moved to the Perpendicular style.

The choir stalls all had to be replaced during the Victorian era following a fire set by an arsonist in 1829. Sadly, no misericords.

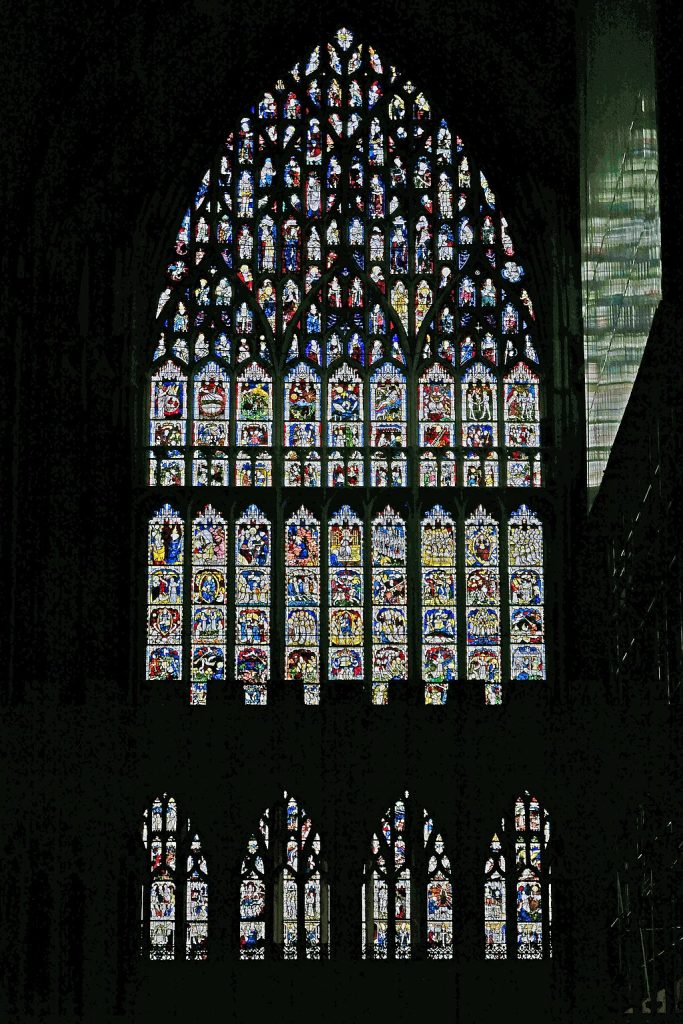

York Minster doesn’t boast much in the way of a retrochoir or chapels in the east. The main attraction is the Great East Window, the second largest expanse of medieval glass in the world at 1680 sq ft (Gloucester Cathedral’s east Crecy Window is larger).

York Minster’s East Window recently undertook a ten-year, $14.9 million ($US) restoration. It’s somewhat ironic that the window was created in one-third of the time it took time to restore it. One of Britain’s greatest glaziers, John Thornton, completed it between 1405 and 1408.

Construction of York’s Chapter House began towards the end of the 13th century. Several features make it extremely impressive. First, it has no central column holding up the roof, which, like the Minster’s Nave, is made of wood rather than stone. The span is large—58 ft, supported by a network of beams that delight engineers today.

The seven windows are almost walls within themselves. Grisaille backgrounds over 140 panels feature figures depicting Christ’s passion and a boatload of saints.

Each window has vertical lights that rise to culminate in three circles.

The Chapter House also contains some beautiful carvings—amusing…

…beguiling

….and frightening!

For all its political and ecclesiastical significance, not one King or Queen has been buried at York Minster. Nor does it hold many monuments for prominent members of local families who seemingly preferred to be buried in their local churches; even local politician Sir Henry Bellasis and his wife, Ursula Fairfax Bellasis, were buried elsewhere; this is just a “wall monument”.

One tomb (I didn’t catch which one) had a winged cherub so lifelike you want to wipe away the tears.

Let’s work out way back through the Minster and take one last look at the magnificent Heart of York window at the West end of the nave.

Goodbye, York Minster. I can’t wait to visit you again.