After four lovely days in Northumberland staying at Eshott Hall, we went southward towards Yorkshire. The lively and engaging people we met at Eshott Hall were all from England, and there was no shortage of advice on what stops to make on the relatively short journey. The town of Durham and its Cathedral, Ripon Cathedral and Beamish all made the list. So many choices – so little time!

In hindsight, I’m really glad we chose Durham. Not only was it beautiful, but it also happened to be one of the six cathedrals featured on a set of Royal Doulton hand-painted antique cabinet plates Glenn gave me for my birthday.

We have seen three of the six (Salisbury Cathedral, Winchester Cathedral and Westminster Abbey), and I had meant to check which were yet to be seen before leaving on this trip, but I forgot. Upon returning home, it was spooky to discover we had covered the remaining three just by chance, and Durham was one of them. The other two were York Minster and Canterbury.

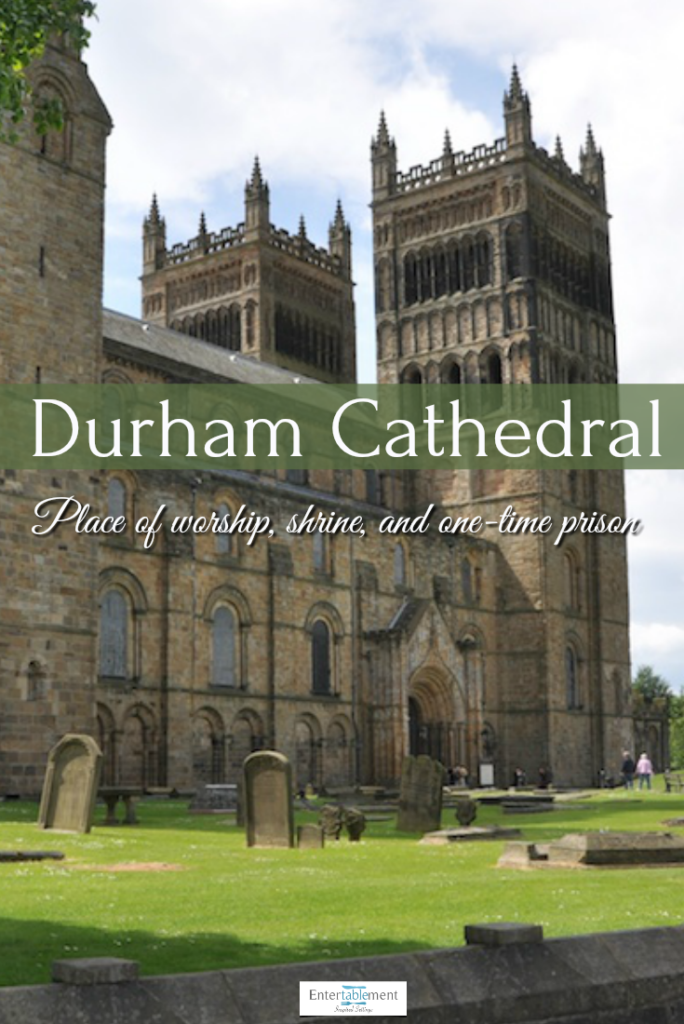

A UNESCO world heritage site, Durham is home to Castle, Cathedral and University. Unfortunately, the castle was closed the day we visited for a private event, so we had to content ourselves with the Cathedral and town.

The present Cathedral was begun in 1093 and is unapologetically Norman, with its square towers and solid appearance.

Perched on a rocky peninsula, the Cathedral served partly as a fortification against the Scots to the north, but also the newly defeated Saxons, who had previously built a cathedral on the site to house the relics of St. Cuthbert, transported in 995 from the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, one of the Farne Islands. St. Cuthbert was a 7th-century monk known for his love of learning and nature, who established a hermitage on the island of Inner Farne, where he died in 687.

The See of Durham (the seat of authority of the bishop) seems to have been a bit peripatetic in its early years. It originated from the Diocese of Lindisfarne, established by Saint Aiden in 635, but was translated to York in 664, then moved back to Lindisfarne in 678 by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Repeated Viking raids saw the monks fleeing from Lindisfarne in 875 to set up shop in Chester-le-Street before finally coming to rest in 995 in Durham.

After the Norman Conquest, the site’s military value garnered a protective castle, a Benedictine monastery and, after 1093, a Cathedral, completed in under forty years. St. Cuthbert’s shrine attracted many pilgrims, happily swelling the coffers of the monastery.

The central tower replaced the original, which was damaged by lightning in the late 15th century.

Its topmost crenellation echoes those on the two west towers, a 19th-century addition where spires used to be.

Below the towers, jutting alarmingly close to the gorge is the Galilee Chapel. You can see how it seems to dance on the edge of the precipice in this aerial shot (not mine).

Legend has it that it was originally intended to be a Lady Chapel, located at the east end (the usual position for a Lady Chapel), but would have cosied up too closely to St. Cuthbert’s relics for the misogynistic saint’s liking.

The more probable misogynist was the creator of the chapel, 12th-century Bishop de Puiset, who made no secret of his disdain for women, going so far as to place a line in the nave floor beyond which women were not permitted to pass. I can only imagine him spinning in his grave at today’s ordained female clergy. The tomb of the Venerable Bede can be seen in the upper left corner of the photo below, against the northern wall. The stained glass is Medieval, which mercifully escaped the smashing clubs of the iconoclasts of the reformation and, later, Cromwell’s thugs.

The stained glass window shown in the centre of the photo below was not so fortunate. It’s a 19th-century replacement of a 14th-century window of the same theme. The technology to create such a large window didn’t exist when the Cathedral was built initially but began to feature heavily in later Gothic architecture. Adding a window of this size would have inserted a welcome amount of light into what would have been a much darker and more sombre interior. Likewise, the choir stalls are from a later period—installed in 1665 in exuberant defiance of the devastating plague sweeping the country.

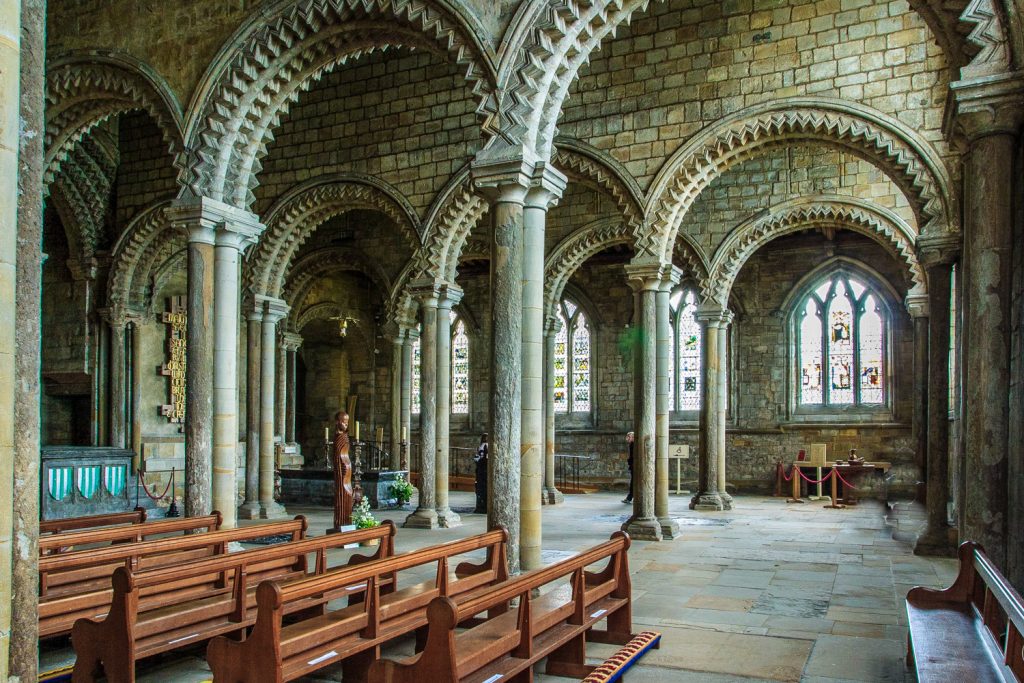

The nave is a rare example of 11th-century Romanesque architecture, with sturdy pillars, alternately round and fluted, incised with fluting, spirals, chevrons and diapering (love that term), whose crevices were once filled with metal and likely very colourful. Though all other English cathedrals of this period have wooden roofs (round arches were assumed inadequate to support the weight of a stone roof), not only is Durham’s roof made of stone, but its vault is ribbed, an uncanny forerunner of the pointed arch which would be a key feature of the still-to-come Gothic period. In addition, the flying buttresses required to counter the enormous outward thrust of the vertical tiers are concealed in the aisle roofs.

Rather than the proposed Lady Chapel, the church’s eastern end now houses the 13th-century Chapel of the Nine Altars, so named for the numerous altars required to accommodate a multitude of pilgrims who flocked to the Cathedral to attend mass and receive blessings.

The addition was begun under the auspices of Bishop Richard Poore, a founder of the new Salisbury Cathedral and a veteran problem solver, sent north to Durham to smooth the waters within the fractious Benedictine monastery next door. Political posturing was typical, with disputes over rank and authority between the Abbot of a monastery and the Bishop of the adjacent Cathedral. It seems Durham was no exception.

The cloisters were the hub of daily activity for the Benedictine monastery. Originally glassed in, the monks exercised, copied manuscripts, taught and studied here.

You may recognize them from the first two Harry Potter movies. Durham’s cloisters and those at Gloucester Cathedral were used in the filming.

Teddy, clad in his Lindisfarne monk’s robe, secretly hopes to be “discovered” for future Harry Potter films. He’s a big fan of magic powers.

Speaking of Harry Potter, the piece de resistance of Durham Cathedral is the Chapter House, which you might recognize as the classroom of Professor Minerva McGonagall, Transfiguration Professor at Hogwarts. Don’t believe me? Check out the YouTube video. 🙂

Back outside, let’s look at the sanctuary knocker on the main door. It’s a replica of the 12th-century original (now housed elsewhere). Until 1623, when the right of sanctuary was abolished, those accused of certain crimes could claim sanctuary for 37 days in the Cathedral, after which they would either have to stand trial or leave the country.

Lastly, before we go, let’s go down to the crypt, which holds the gift shop, where Teddy acquired his monk’s garb.

Durham is fortunate to have survived the Dissolution of the Monasteries with much of the structure intact. The buildings surrounding the Cathedral speak to its rich history as the centre of a thriving community.

The combination of the Cathedral, Castle and the actual town of Durham make for a full day out. Well worth the visit!