Exeter is a scrumptious frothy wedding cake of a cathedral with the longest continuous vault in Europe. While it retains its sturdy Norman towers, the majority of what we see today is of the exuberant Decorated gothic design and was completed around 1400.

Following the withdrawal of the Romans in 410 AD, Devon and Cornwall remained committed to Celtic Christianity. But after the Synod of Whitby in 664, Roman Christianity prevailed, and the Archbishop of Canterbury assumed control of episcopal appointments. In 1050, the Cornish dioceses of Creditor and St Germans were merged under a new Cathedral for Devon and Cornwall at Exeter, just in time for the Norman Conquest in 1066. Busy with Harrying the North, the Normans get around to starting a new Cathedral in Exeter until 1112. The two towers flanking the nave are all that remain of that project.

The towers stand nearly separate from the rest of the structure, providing an interesting visual break of the northern and southern aspects. I think they look like castle towers with their topmost crenelations, small, square turrets and what look like flying pennants. Lady Guinevere, is that you up there?

In 1258, Bishop Bronescombe participated in the celebration to consecrate the newly completed Salisbury Cathedral and came home with a bad case of Cathedral Envy. It took him a while to get the design and funds together, but in 1275 demolition and rebuilding had begun in the then-prevalent Decorated style under builder Master Roger. By 1315, construction was still ongoing; Thomas of Witney, then master builder at Winchester, took over at Exeter and produced what we see today, the closest Cathedral to Salisbury in terms of design cohesion. (Salisbury was built from start to finish in 38 years, an incredible feat).

In 1338, a new Bishop, Grandisson, left his mark on the west front with a low screen of sculpture, similar to what we might find at Wells or Lincoln. But, unfortunately, it wasn’t completed until 1375; by then, Grandisson had passed away, and the Black Death had finished off the designer, William Joy.

They’re all covered with a fine mesh, presumably discouraging birds from nesting.

The lowest of the three tiers of sculptures are angels, with kings and knights above them. Saints and apostles comprise the top row. Some are sitting, others are standing, and a few have their legs crossed; two are arguing. Initially, the images would have been entirely coloured; it’s difficult to imagine what a vision that might have been!

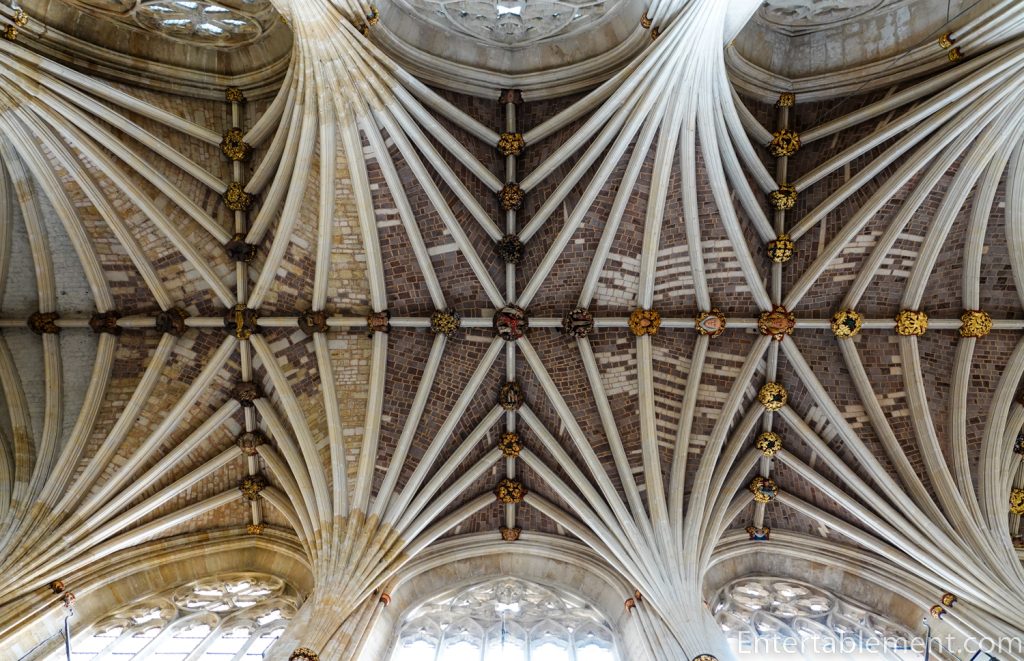

Inside, we are greeted with Decorated ebullience as far as the eye can see.

Looking up, the vaulted ceiling is a cluster of arch mouldings and ribs, dotted with what look to be tiny little bosses.

Don’t be fooled.

They’re huge. They are the keystone’s carved bottoms that hold the vaults in place.

See what I mean? They’re about three feet in diameter, and some weigh two tons. So it gives you some notion of how high that ceiling vault is!

The bosses are the usual cast of characters: monsters, monarchs and biblical scenes, with baskets of gilded foliage in between.

There is even one depicting the martyrdom of Thomas à Becket of Canterbury Cathedral.

The pillars (or piers, as they’re also called ) comprise sixteen shafts with eight mouldings to each arch. The piers are made from Purbeck marble, and the shafts are creamy limestone.

With so much to see, it’s easy to miss details, such as these faces topped with elaborate gilded profusions that look like giant headpieces.

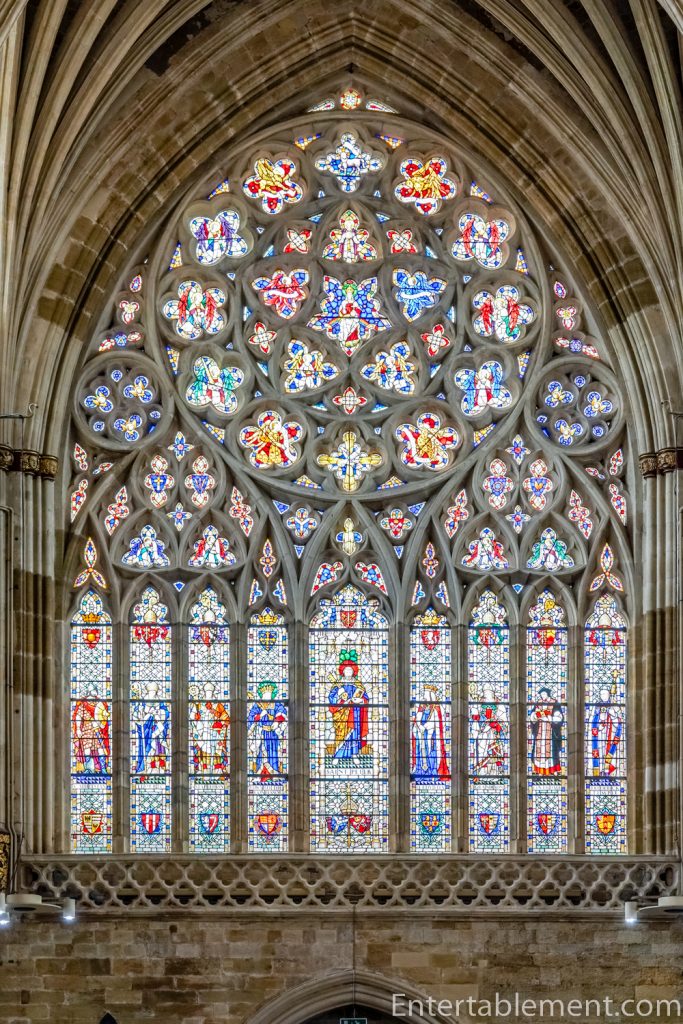

Above the west door is a Decorated Gothic rose window filled with leaded glass.

The minstrel’s gallery sits high on the north wall, with a frieze of colourful angels playing musical instruments—bagpipes, harp, gittern, shawm and portative organ (according to the website); I’m not sure what half those instruments are. The gallery was likely used by musicians or singers, though that is not certain. Behind the balcony is a section of the cathedral organ, which carries additional sound directly into the centre of the nave.

Because Exeter doesn’t have a central tower, it doesn’t have a crossing; the two towers form transepts of a sort. In the North Transept is an astronomical clock (the turquoise square below), a working model of the solar system as it was understood.

The gold ball in the centre represents the earth. The black ball with the fleur-de-lys represents the sun, and it circles the dial every 24 hours, with the outer ring marking the time of day and the inner ring is the day in the lunar month. The black ball represents the moon. Half of its surface is black, and the other half is silver; it rotates on its axis to show the correct phase of the moon.

PEREUNT ET IMPUTANTUR means ‘The hours pass and are reckoned to our account’.

During the 18th century, the circle above the square astronomical clock was added to track the minutes (probably not a pressing concern in medieval times)!

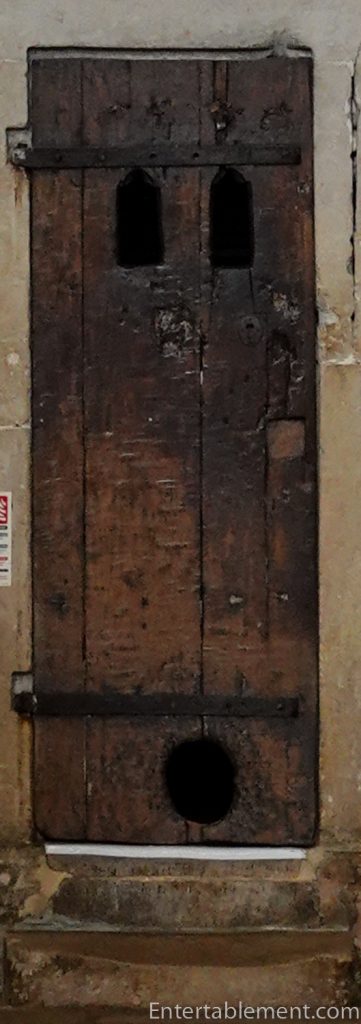

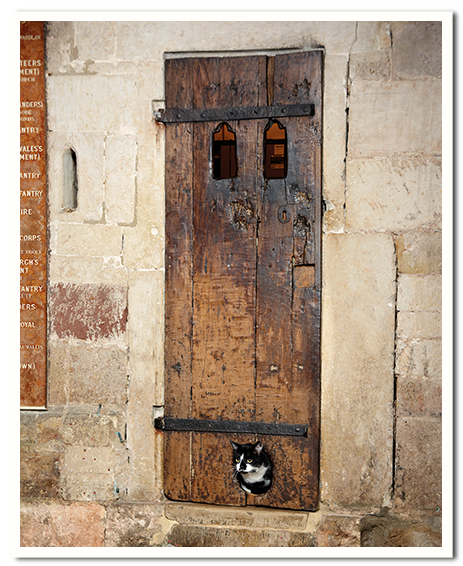

Now, for another fun feature. See the hole in the door below the clock? It’s the oldest existing cat flap in a Cathedral in England, installed because the clock developed a rodent problem. The ropes, lubricated with animal fat, were a magnet for mice (and rats). So the cat flap was installed to allow cats to deal with the gnawing intruders.

The cats were paid for their services, believe it or not! Since 1305, cathedral accounts show an allowance for quarterly payments of 13 pence (or a pence a week) to custoribus et cato, or, if Latin is not your first language, “to the custors and the cats”. And what’s a custor, you might ask? Likely what we would today call a custodian. They were in charge of bell ringing, looking after vestments and keeping visitors in order. Oh, and looking after the cat. I have visions of the cat lining up for his weekly pay packet and consulting an investment advisor on how to best save for his retirement, but I suspect the funds were used to purchase food for the feline. Cats cannot live on rodents alone!

The Cathedral’s current cat is named Stapledon. He welcomed people back after the Cathedral re-opened when social distancing restrictions were lifted.

The South Transept contains the tomb of the Earl and Countess of Devon, who died in the 14th century.

You might be wondering what on earth those large pipes are. They’re organ pipes. With such an enormous nave, they’re needed to carry the sound.

Let’s go back into the nave and work our way east, where we see the pulpitum with its three arches surmounted by an openwork balustrade. Created by Thomas of Witney, it dates from 1324.

The panels in the balustrade each contain a Jacobean painting of a biblical scene, which replace panels destroyed during the Reformation (no doubt they held graven images, a big no-no at the time). Next time I visit, I must get better close-ups of the carved foliage in the triangular sections between the arches. They’re almost like lace, so deeply cut they are into the surface of the stone.

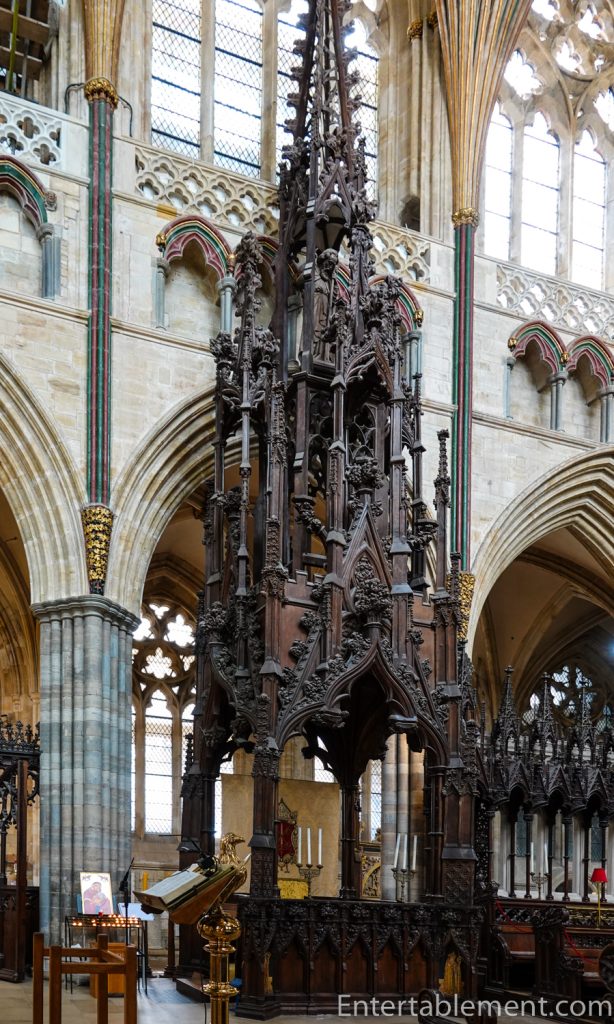

The Martyr’s Pulpit is just to the left of the Pulpitum, erected in memory of Bishop John Coleridge Patteson who was ordained in the Cathedral. The detailed carvings might lead you to think it’s made of wood, but it’s very evenly-grained sandstone. Designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott in the 1870s, its detailed and lifelike stone carvings have been described as the pulpitum in miniature.

In 1855 Bishop Patteson travelled to New Zealand and the Pacific islands of Melanesia, where he devoted the rest of his life to the peoples of Melanesia, becoming their first bishop and learning more than 20 of their languages. Unfortunately, he was murdered on the island of Nukapu in the Solomon Islands in 1871. The panel below depicts three islanders placing Bishop Patteson’s body in a canoe to be returned to his ship.

Andrew Dickson White Architectural Photograph Collection, #15-5-3090. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

The figures of three early Christian martyrs are also carved on this pulpit: St Stephen, St John the Baptist and St Paul. Not sure which one this is, but the subject reminds me of my mother, who dismissed sighing, or long-suffering behaviour as acting like an “early Christian martyr”.

This panel depicts the beheading of St Alban (of St Albans Cathedral), the first British Christian martyr, around 300AD, during the Roman occupation of Britain.

Through the pulpitum, we are in the choir, where we can begin to see the delights in the eastern end of the Cathedral.

The Great East Window at Exeter is stunning. Nine figures date from around 1304; the three at the top of the window are Abraham, Moses and Isaiah, from the lettering on their scrolls. The other six are the outer figures of the bottom row, but the faces of these saints are not original. By 1390, the stonework of the original window had become unsafe, and a new window In the Perpendicular style was constructed. This is the tracery we see today. The original glass was mixed with new when the new window was completed in 1391.

The glass was removed and stored safely during World War II. And a good thing, too. Almost all of the glass in the Cathedral was damaged beyond repair during the extensive bombing of Exeter in 1942.

George Gilbert Scott reconstructed the choir stalls in the 19th century, but the canopies, misericords, bishop’s throne and screen are all original.

The misericords are a real treat, stunningly detailed. You’d almost think it was a buffalo.

A monk is playing the flute and beating a drum.

Noah’s Ark and a giant seabird, I think.

I got absolute pleasure in looking at the “handles” on the seat. They must leave a real bruise if you sit down clumsily.

The squirrel is so lifelike!

Okaaayy…a monkey with a hat?

This one has me stumped, too. With the long lower portions of the back legs… a pine marten? With his ears back?

The more extensive carvings on the ends of the rows were stunning—a not-unexpected couple of angels.

But a whale?

A crocodile, of all things!

And my absolute favourite – an elephant.

Looking back through the choir towards the West End, we get a good view of the organ.

The Bishop’s Throne, designed for Bishop Stapledon (for whom the current Cathedral Cat is currently named) is tucked in at the centre of the south (right) choir stalls. Thomas of Witney designed it in1313 and was paid the fantastic sum of 12 shillings to complete it in a month. Originally, it would have been gilded and painted.

From this throne, William of Orange read out a “declaration of peaceful intent” in 1688 after he came to England to rule jointly with James II’s daughter Mary, to whom William was married (yes – that Wiliam, of William-and-Mary). Backstory: Mary was Catholic, like her father, James II, who had been “encouraged” to abdicate because of it. William of Orange was protestant, So let’s make sure that the country continues to be Protestant by making the couple rule together and stamp out any pesky notions of Mary trying to take us back to Catholicism again like Mary (Bloody) Tudor tried to do not long ago.

And speaking of thrones, the nearby sanctuary contains Thomas’s exuberant, triple-level sedilia, each with a gilded canopy above, topped by another niche containing a statue with another canopy above. Remember I spoke of Exeter being a Cathedral with the confection of a wedding cake? Behold!

Hugh Llewelyn from Keynsham, UK, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

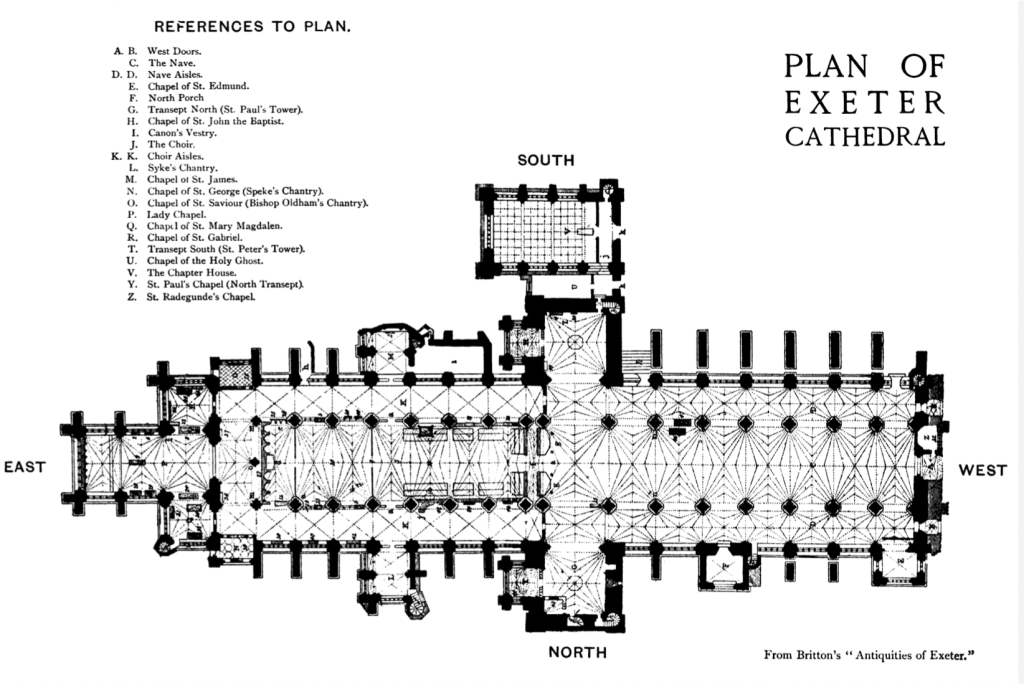

East of the Sanctuary, the real estate becomes complicated, with multiple small chapels and the Lady Chapel, as shown on the floorplan below.

What is instantly evident is colour—lots and lots of it due to the restoration work by 20th-century medievalist E W Tristram. Painted angels beam down.

And Bishop Oldham (1504-16) is buried in a great and colourful state, despite his famous (or infamous) ongoing battle with Richard Banham, abbot of nearby Tavistock Abbey, who declared his abbey exempt from the bishop’s right of episcopal visitation. This battle of “who’s boss?” between bishops and abbots within the same district was widespread, with the more independently-minded abbots sometimes appealing directly to the pope, where (for a small sum, of course) they were sometimes granted permission to report directly to the pope, and bypass the local bishop’s authority. It was thus, in this case, threats of (and in some versions of events, actual excommunication of the abbot by Bishop Oldham.

Through the canopy of the tomb, we can see the ceiling of the Chapel of Mary Magdalene.

The pièce de résistance is the Lady Chapel.

Isn’t the window stunning?

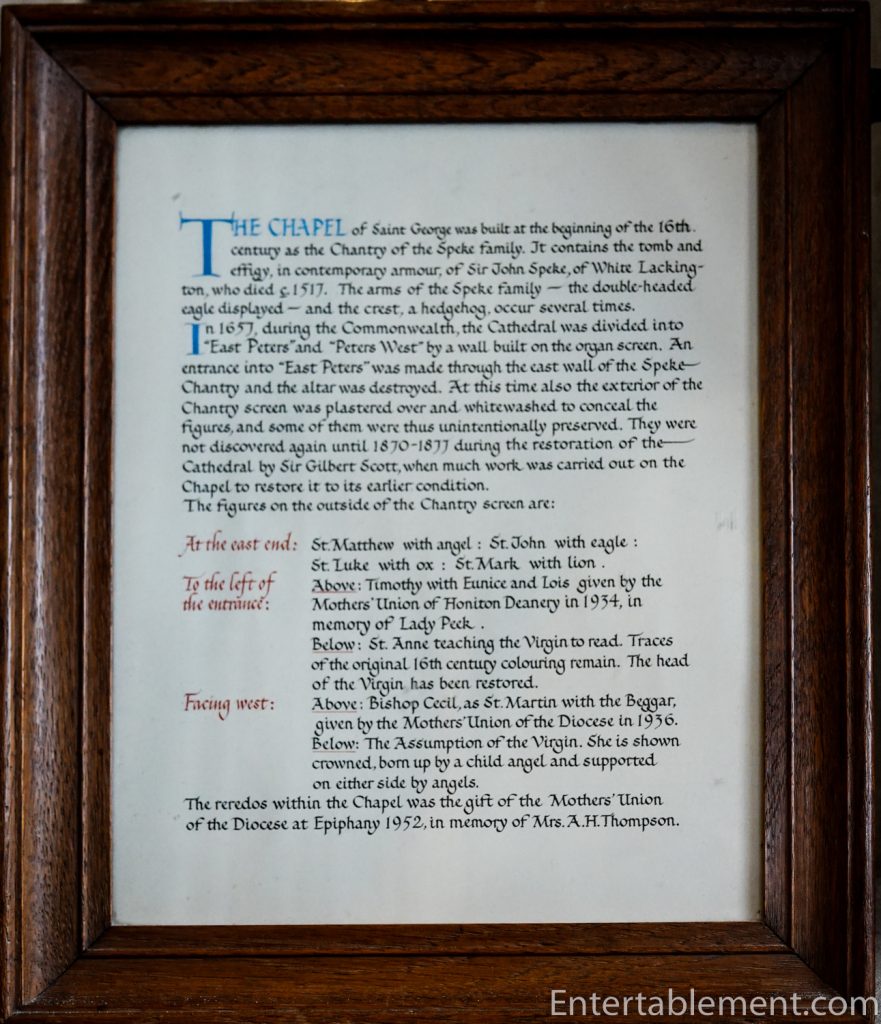

The Chapel of St George was built in the early 16th century as the chantry of the Speke family.

It contains the tomb and effigy of Sir John Speke who died in 1517.

Anyone tempted to tut-tut the graffiti habits of today’s youth might be relieved (or horrified) to discover this practice has a long history. The alabaster effigy of Bishop Edmund Stafford, who died in 1419, is liberally defaced with very old scratches.

Looking out into the choir aisle from the chapel of St Gabriel the Archangel

Exeter is currently undergoing a Development Appeal to do considerable work to the East End of the Cathedral, including building out the Cloister Gallery, which will be about half the footprint of the Cathedral.

Like Carlise, they recently renovated the Chapter House for corporate functions. It’s a good-sized space with lots of light and a high, vaulted ceiling.

Built around 1227, it contains the grave of Serlo, the first Dean of Exeter, who died in 1231. Secular (as opposed to monastic) Cathedrals are led by a Dean rather than an Abbot. Serlo was also the Archdeacon of Exeter, with administrative authority delegated by the bishop, over the diocese of Devon and Cornwall. The Cathedral also had a Precentor for music, a Treasurer to guard the movable property (including the bells) look after lights and security (and pay the Cathedral Cat). 🙂 The Chancellor oversaw the 24 prebends or “livings”.

The Chapter House was where The ‘Canonici Prebendati’ met on Saturdays; their decisions were recorded in Chapter Acts, many of which still survive in the Cathedral Archive. It’s fascinating to know that the Chapter House was in continual use, except during the Commonwealth period (1646-1660).

The building burned down at the beginning of the fifteenth century and was rebuilt in about 1412. In 1820 it was fitted with shelving to accommodate the Library; this was removed before the end of the century.

The sculpture work you see below is modern, by Kenneth Carter (1974).

I’m eager to view the finished product. I am very heartened to see the focus on generating renewed interest in Cathedral buildings while creating a viable source of revenue through repurposing existing structures.

Exeter Cathedral is an excellent example of Decorated Gothic architecture in its purest form. It’s a miracle it survived the bombing of 1942; the surrounding area was flattened and rebuilt in depressingly post-war fashion: in a hurry and on the cheap. I’m delighted that the powers that be are working to beautify the grounds around the Cathedral and give us a better sense of what they might have looked like with the cloisters.