Before Westminster Abbey, Winchester was the big noise for coronations and royal burials— the capital of Saxon England and the seat of power. By the time William the Conqueror arrived in 1066, its church was the burial site for 17 kings.

Winchester had churches as early as 164, but the first Christian building appeared around 650. The Old Minster, as it was then known, became increasingly prominent, growing in stature and size. In 662, it became the seat of the new diocese of Wessex (later Winchester).

Within its precincts, one of its early bishops, Saint Swithun, was buried in 862. Then, in the 10th century, the Benedictine Priory of St Swithun was established, using The Old Minster as their priory church.

Somewhat weirdly, King Alfred The Great began a competitive Benedictine monastery, imaginatively named the New Minster, on the same site. (Why? I have no idea…). After extensive renovations and additions, it became the largest church in Europe. (I think we begin to have a clue here – overweening ambition disguised as religious fervour, perhaps)?

Saint Swithun’s body was removed from the precincts of the Old Minster and enclosed in a new and improved indoor shrine in the New Minster. Step right up, folks, and get your healing/blessing from our very own patron saint, Swithun!!! Donations are happily accepted.

Apparently, the buildings were so close that the voices of both choirs merged, creating a cacophony.

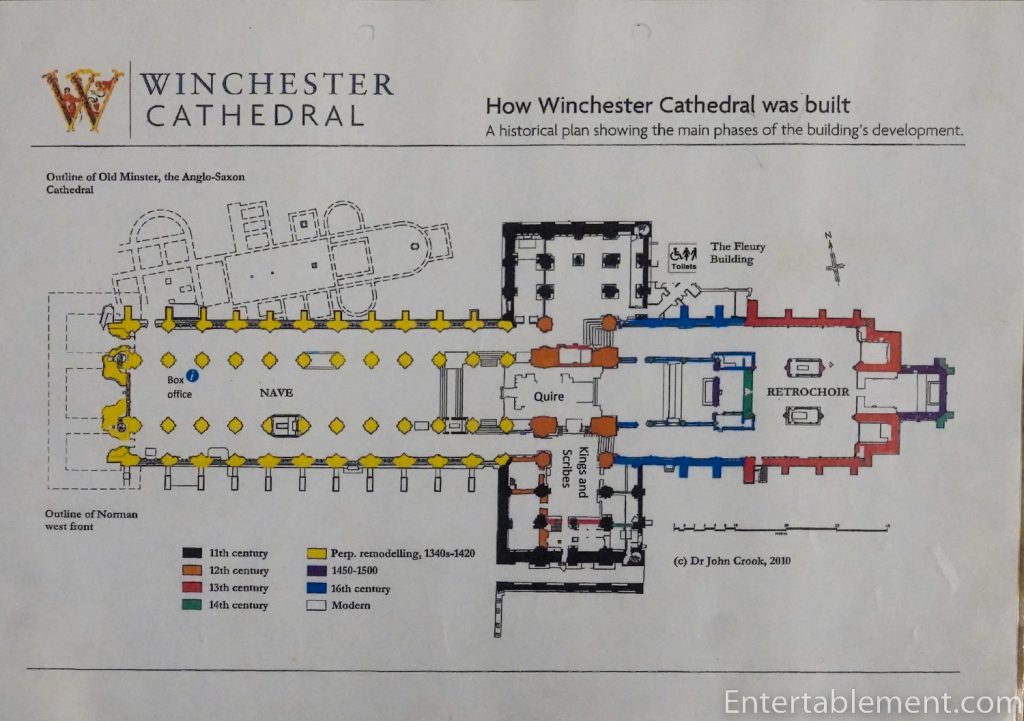

After the Norman Conquest, the dual (or duelling) monasteries came to an end. The monks of New Minster moved to Hyde Abbey on a new site north of Winchester. In 1079, both Old and New Minsters were demolished, and work began on the present Cathedral. At 558 ft, it is Europe’s longest Gothic Cathedral overall.

The current Cathedral is the result of extensive remodelling by successive bishops over the ensuing five centuries. As a result, it’s remarkable in encompassing many architectural styles—an early Norman crypt, a Perpendicular Gothic nave and several Renaissance chantry chapels. Its interior is fabulous; the exterior is a bit cold and forbidding—John Goodall, in his article about Winchester Cathedral in Country Life Magazine, describes it as “undemonstrative”.

Regrettably, it sits on shaky ground—literally. By the 20th century, things had reached a perilous juncture. Only the heroic efforts of William Walker, a diver of all things, rescued the Cathedral from complete collapse.

Between 1906 and 1911, working in water up to 20 feet deep, Walker toiled in six to seven-hour shifts, five days a week. He descended into cramped trenches, wearing an ungainly 200-pound diving suit, replacing sodden peat topsoil that comprised the Cathedral’s foundation with bags of concrete—25,800 of them. Can you imagine?

(Image: Picture courtesy of the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Weather Book by Mark Davison, Ian Currie and Bob Ogley (Froglets Publications).

It’s even more astonishing that 900 years passed before things really got serious. When construction commenced, the unstable foundation was recognized almost immediately. The tower collapsed in 1107 and was wisely not replaced.

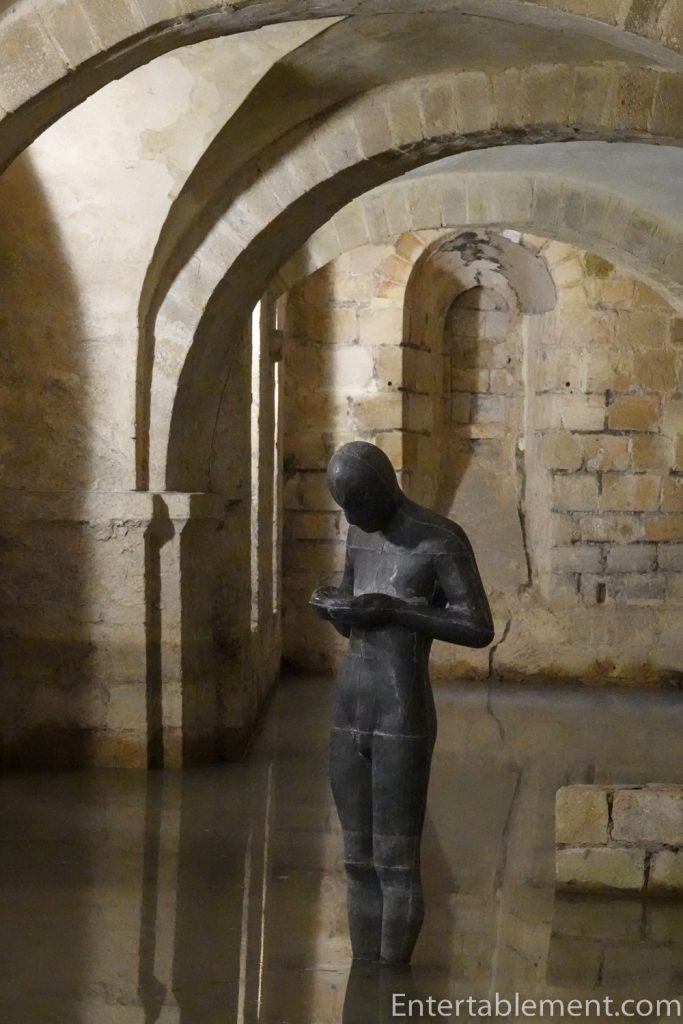

Some of the earliest stonework completed, the great Norman crypt survives intact and is still regularly flooded.

Sir Anthony Gormley’s Sculpture, “Sound II”, stands in the Crypt, holding water in its cupped hands. At first glance, I thought the sculpture was a commentary on the perils of social media, as it looked like he was texting. But no. The sculpture was installed in the 1980s, long before we became automatons glued to our screens, in precisely that posture. Water rises from a tube mechanism through the body. It’s apparent from the water lines on both the sculpture’s legs and the surrounding walls that the water rises quite a bit higher than it was when we were there.

It was one of the most welcoming Cathedrals we visited, with helpful guides everywhere we turned, answering questions and inviting us to visit the library on the second floor of the south transept.

The education centre on the third (clerestory) is very well done. We spent a long time up there, looking at models of the Cathedral in various stages of completion.

They also have a fascinating video on computer modelling of the bones excavated during the various Minster rebuildings, reinterred in the mortuary chests perched high above the choir. Creepy but fascinating!

Winchester is a story of many Ws. William the Conqueror installed Walkelin as the first Norman Bishop of Winchester in 1070. He began work on the Cathedral in 1079 and worked with commendable speed; by 1093, the east end was completed, and four years later, the transepts and central tower were complete. Unfortunately, the tower fell in 1107, likely interrupting work on the nave, but it was finished by 1129, an astonishing accomplishment—500+ ft of Cathedral, from east to west, completed in 50 years.

Despite its waterlogged foundations, it’s a very sound building. If Bishop Walkelin were alive today, he would recognize the transepts he built.

Rounded Norman arches and a wooden ceiling.

He’d have a more challenging time with the nave, but that’s because the interior has been reclad, not because it was taken down and rebuilt.

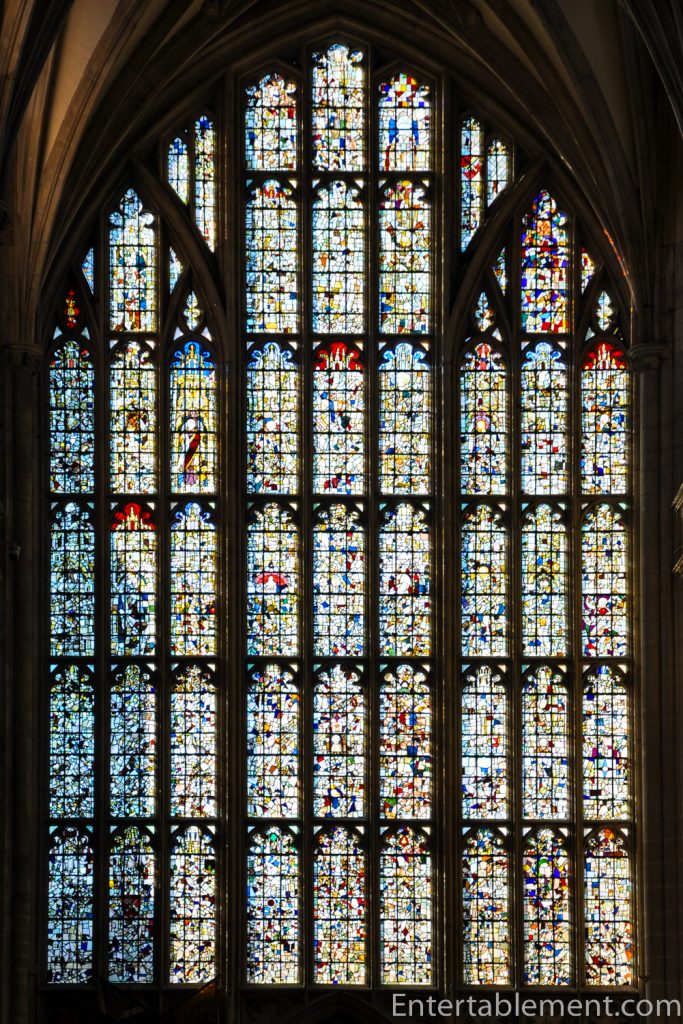

In 1346, one of the few non-Ws, Bishop Edington, replaced the Norman west front with a new Perpendicular Gothic facade containing the vast west window we see today.

Inside, William of Wykeham and his mason, William Wynford, wrought significant changes to the nave. Wykeham also established nearby Winchester College, founded in 1382 for New College Oxford. The school, whose motto is Manners makyth man, is still known for its academic rigour, and its graduates are called Wykehamists.

They chiselled Gothic mouldings into the Norman pillars and cut pointed arches into the round Norman openings.

At the same time, they reorganized the three-tiered nave into two tiers by extending the arcade (first layer) upward and extending the clerestory (top layer) downward.

You can see it illustrated in the model below—the original three tiers (arcade, triforium, clerestory) are on the right, and the reorganized two-tired (arcade and clerestory) nave is on the left. Isn’t it amazing?

The central section of the model, with the soaring round arched first layer, is part of the crossing below.

Here it is, straight on. I got this shot from the clerestory level of the South Transept, looking through the crossing into the North Transept, which houses the organ (currently undergoing a massive restoration).

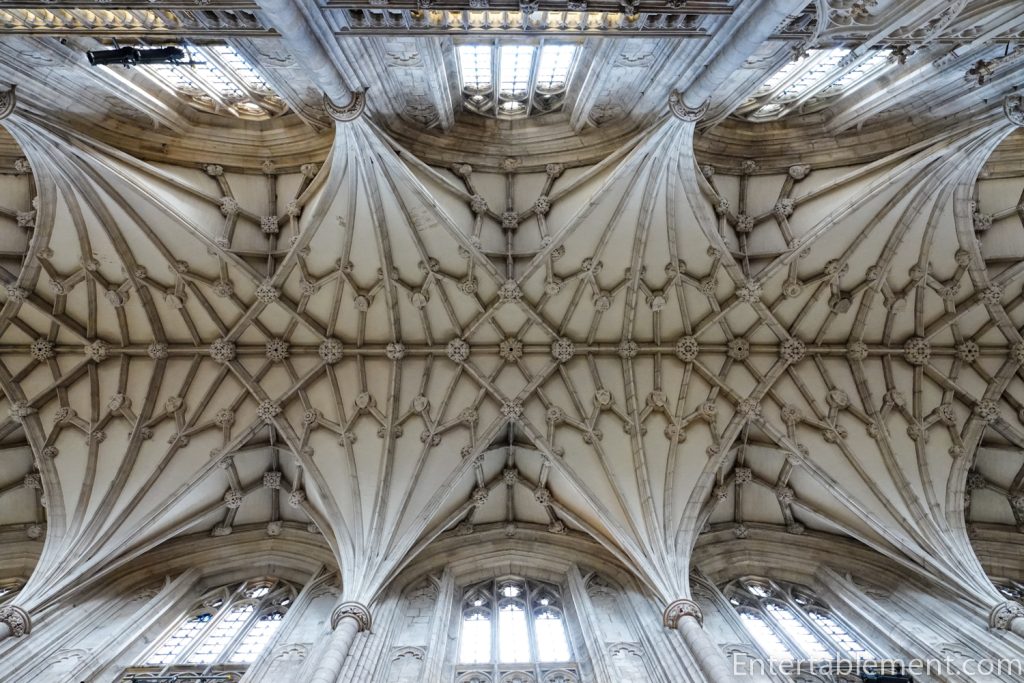

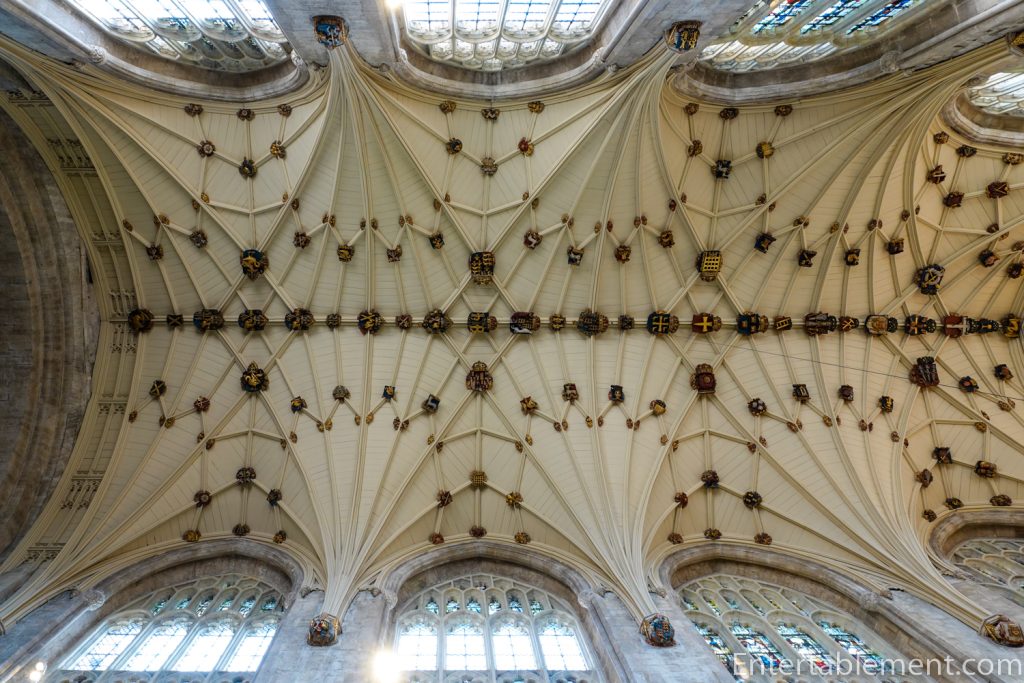

Back in the nave, a decorative stone vault replaced the wooden ceiling.

The remaining surfaces were newly encased in ashlar stone. Voila, Perpendicular Gothic Nave.

Following Wykeham’s death in 1404, successive bishops carried on with the work, which was completed around 1420. The short, highly decorative rectangular structure you see below is a chantry chapel.

Winchester has seven of them; most of them are in the retrochoir. They’re quite something—more on those later.

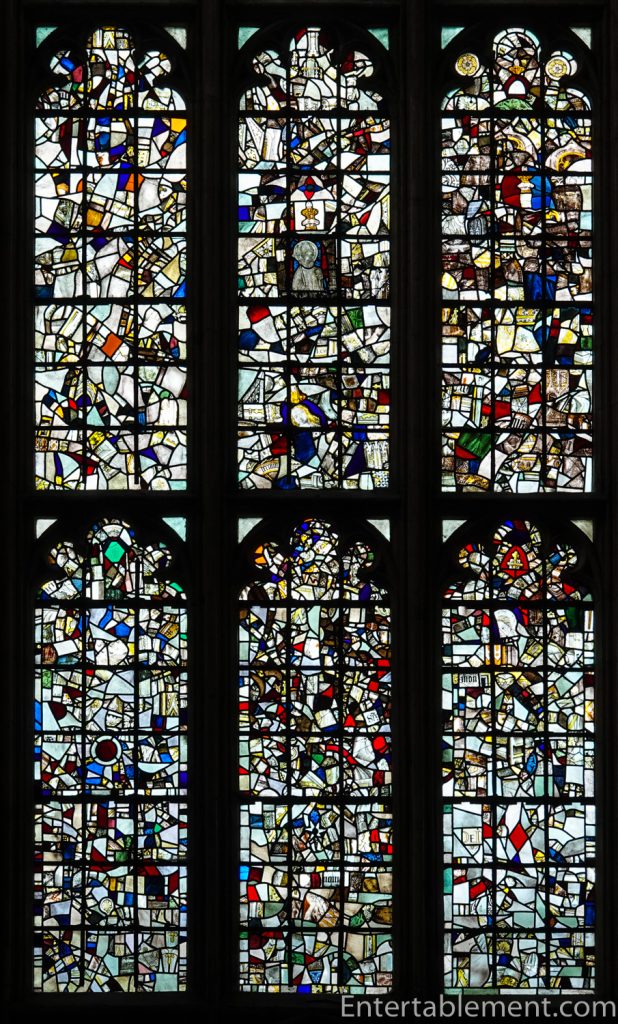

Inside, the great west window looks incredibly modern, filled with glass in an abstract mosaic pattern. Don’t be fooled. Cromwell’s parliamentary thugs smashed the medieval stained glass to smithereens in December 1642.

After the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Winchester’s townspeople reassembled the window from the shards of glass that had been swept up from around the church—recycling at its finest.

From 1450 to 1528, successive bishops focused on the choir and retrochoir, replacing the Norman east end with a Perpendicular Gothic presbytery and extending the retrochoir into a Lady Chapel. Here we look through the choir into the Presbytery (Sanctuary) with its highly decorative reredos (screen) behind the high altar).

This shot of the choir faces the other direction, towards the west window. George Gilbert Scott installed the intricate wood screen at the west end of the choir in the 1870s as a part of the Victorian restoration.

Facing east again, we can take a closer look at the reredos and great screen in the Presbytery, built between 1450 and 1476.

The original statues were smashed during the Reformation and restored in the 1870s by J. R. Sedding.

No good deed goes unpunished, however. The restored statues were criticized as being overly ornate. Fair point. Still, they do fit very well with their surroundings.

High up on the screens on the north and south of the Sanctuary are the mortuary chests reported to contain the bones of Saxon kings previously buried in the Old Minster, including the bones of Egbert and Canute.

During the Civil War, the bones were scattered but gathered up again and put back into the trunks, though whose went where is anyone’s guess. The re-constructionists must feel like they’re assembling a jigsaw puzzle with pieces from several boxes.

The Presbytery vault is wood, painted to look like stone, similar to the one at York Minster.

The wooden planks are noticeable when you zoom in closely. It looks like the hull of a ship.

Because of the extensions, the east end is about 110 ft longer than Walkelin’s original building. We are now standing just behind the Sanctuary, looking at the easternmost part of the Cathedral, with the seven-panelled window in the Lady Choir in the distance.

The metal frame in the middle marks the spot where St. Swithun’s shrine lay, which was destroyed in 1538 during the Dissolution of the monastery. Not quite sure what they’re thinking with this marker—it looks a bit like a barbecue or a jeweller’s display case.

The retrochoir is the home of several chantry chapels dedicated to former bishops at Winchester. These highly ornate structures are chapels endowed for the saying of masses for the founder’s soul after his death to speed his way through purgatory.

On my first visit to Winchester about a decade ago, I completely missed this part of the Cathedral. Heaven only knows how—it’s the best part! We are looking west, into the back of the reredos and great screen.

The earliest known chantry in England was built around 1235 for Bishop Hugh of Wells in Lincoln. The practice was abolished by Henry VIII’s son, Edward VI, during the latter part of the Reformation. However, Winchester got theirs in under the wire, and they miraculously survived the destruction of Cromwell’s troops, who were determined to stamp out any vestiges of “popish practices”.

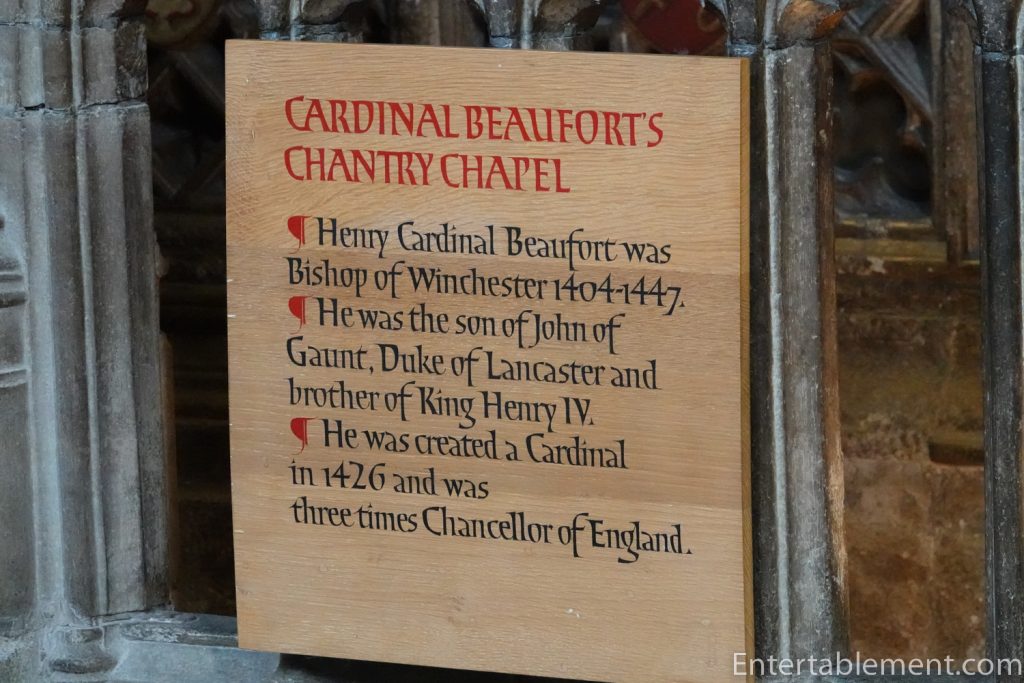

This one is dedicated to Cardinal Beaufort, a very big noise in the annals of Winchester’s history—Bishop of Winchester from 1404-1447, and previously the Bishop of Lincoln.

As was typical for the second son of the nobility, he entered the church. Subsequently, he rose to a very powerful position as Chancellor of England and a Cardinal.

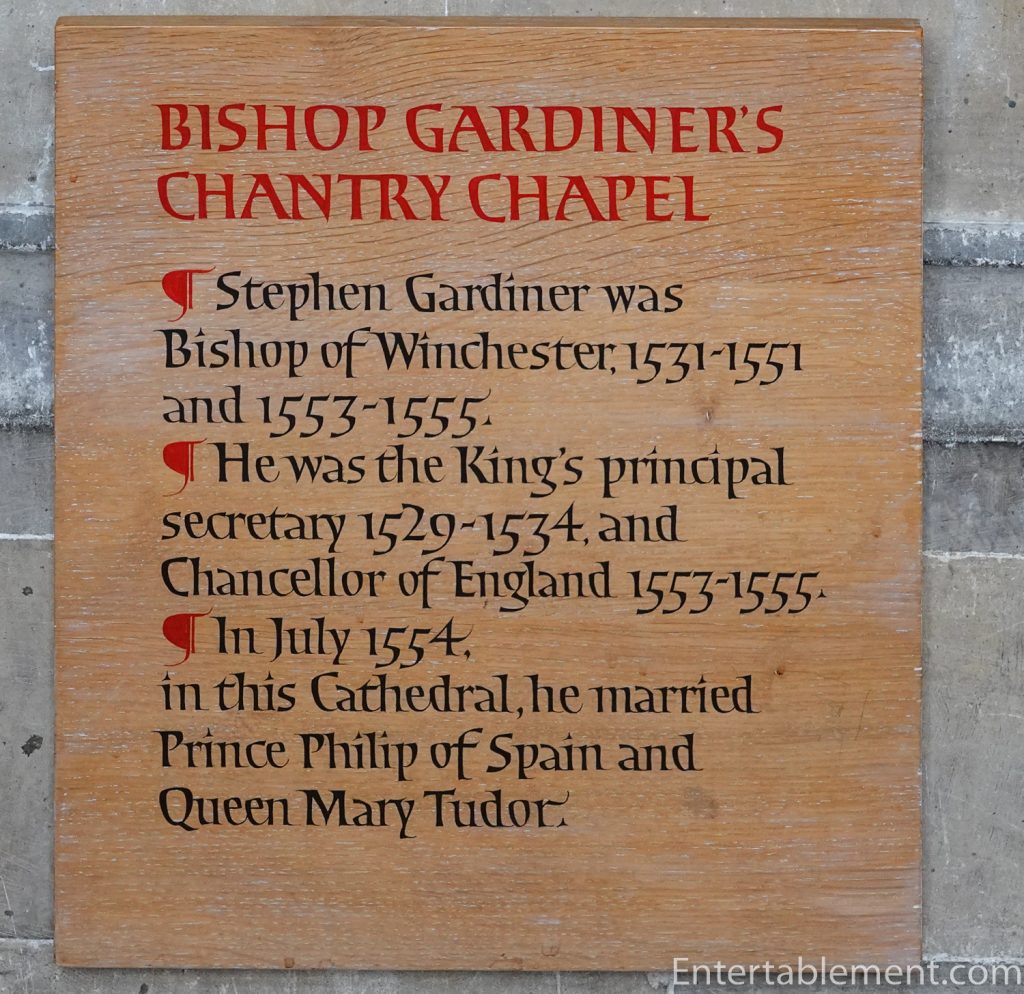

Though also very prominent, Bishop Gardiner has a much more modest resting place. He performed the marriage ceremony of Catholic Philip of Spain to Mary Tudor (Henry VIII’s eldest daughter, who headed up the counter-reformation, turning England back to Catholicism for a brief and bloody period in the 1550s).

Perhaps ostentation was dying out, or funds had run short, but he looks like he’s been incarcerated.

There are three chapels at the far eastern end of the retrochoir, including the central Lady’s Chapel shown below.

It was extended in the 15th century.

The paintings depict miracles, including Lazarus being raised from the dead.

The ceiling, capping three beautiful stained glass windows, is just gorgeous.

The Guardian Angel Chapel was painted in 1241 under the direction of King Henry III, also known as Henry of Winchester.

He was the son of the one and only King John and ascended to the throne when he was only nine.

The painted ceiling is remarkably well preserved, though I find the angels ghoulish.

We have reached the end of our tour, and I am very sorry to leave Winchester. Let’s stop for a cup of tea in the nearby visitor’s centre and cafe, which attracted a design award.

I was quite impressed with it. The leaded roof allows the low-profile building to blend right into the surroundings.

We then made our way along the side of the Cathedral, back to where we had left our car, just outside Winchester College. I was dying to go in, as it’s also famous for its architecture, but it was an open day for prospective students—not a good day for nosy visitors.

Into the car and on our way. Our next stop on this journey was the Isle of Wight to see Oborne House.