Good day, everyone, and welcome to Harewood House Part II. Sorry for the delay in providing the sequel to Harewood House Part I. Travel and the holiday season got the better of me in the intervening period, but I’m determined to tie off as many loose ends as I can before the New Year is upon us. To resume our journey, we left off in the dining room, where I was actively coveting the Millefiori dessert service. From there we moved belowstairs to the kitchens, source of all the delicious sustenance that graced the beautiful tableware in the dining room

Typical of the era, and suitable for the scale of the house, the kitchens are massive. They’re also a bit out of the ordinary. Aesthetically, they’re very pleasing. Light, airy and cosy despite their spaciousness, the kitchens at Harewood benefitted from their architect’s deep knowledge of stone, brought to life by a highly-skilled workforce, and supported by a patron who wanted only the best for his estate. The happy result is kitchens of exceptional quality, particularly seen in the beautifully cut masonry on the walls, skirtings, door surrounds and a huge vaulted roof whose shape echoes the ceiling of the Sistine chapel.

The kitchens were restored in 1996 and the public had its first peek at the world belowstairs in this great house. During the restoration, layers of accumulated whitewash were removed, revealing the original painted finishes of 1774. Cupboards were banished to make room for the return of the charcoal stove. Most impressive of all was the wealth of copper-ware, brought out of storage, catalogued, cleaned and returned to its original shelves.

Upon her arrival at Harewood, the London Housekeeper of Edwin Lascelles, the 1st Earl of Harewood, warned her Harewood colleagues to prepare for ‘a great deal of grandeur’; Mr. Lascelles expected all dishes to be prepared in the French style, å la mode de Paris. The family entertained lavishly. And in case you think there were dozens of staff on hand to assist, you’re in for a bit of shock. In the 1780s, the Head Cook, Walter Windeyer, and three kitchen maids were responsible for all the family’s meals, the servant’s meals and all of the banquets that were prepared. The Head Cook and the House Steward were the most highly-paid servants at £94 per year. The kitchen maids were paid £8 to £10 pounds per year.

The kitchen got a refresh with the advent of the 3rd Earl and Countess and their thirteen children in the 1840s. Upstairs, extensive renovations were underway under the direction of architect Sir Charles Barry. Down here in the kitchen, old equipment and fittings were replaced, a charcoal stove was installed and a brand new set of copper pots, pans and utensils were purchased. The Head cook was still the most highly paid servant and for good reason. During the month of December in 1880, for example, over a ton of meat was cooked and 1200 dinners were prepared, 102 of them on Christmas Day alone. The servants of yore were clearly made of sterner stuff than those of us who have just prepared Christmas dinner for our families and needed two days to recover.

Electric light was installed in 1901, but not much else changed belowstairs. King Edward VII visited in 1908 to great pomp and ceremony. The onset of the First World War, however, brought great changes. The 5th Earl and Countess moved into the East Wing and the house became a convalescent hospital for wounded soldiers. When the war ended, the kitchens were once more used by the family, but the days of the lavish lifestyle were over. In 1930, HRH Princess Mary and her husband, the 6th Earl moved to Harewood and a programme of restoration began. The Victorian kitchen range gave way to an efficient, modern unit by Benham & Sons of London. Harewood once gain buzzed with activity as Princess Mary’s parents, Queen Mary and King George, made regular visits along with other members of the Royal Family. The Second World War saw the house used once more as a convalescent hospital and the kitchen provided all the food for the servants and staff. The family’s meals were prepared in the former Housekeeper’s room, now the Still Room.

Below is the vegetable scullery, which was added in the 19th century. Here a Scullery maid washed and prepared all the fruits and vegetables. The estate has an extensive walled garden, pictures of which we will see in a minute. It’s over on a small island, down a steep hill and accessible by small ferry boat. When the first Earl, Edwin Lascelles lived at Harewood, the kitchen gardens grew “bananas, eggplant, sugar cane, alpine strawberries, kidney beans, grapes … cucumbers, oranges, figs and peaches”. Quite an exotic assortment of produce! Who says the British don’t eat well?

Further down the hall from the scullery was the small housekeeper’s room, where this beautiful tea set caught my eye.

I wasn’t able to get close enough to discern the floral motif with certainty, but it looks like Lily of the Valley to me. What do you think?

Next was a bank of doors, which we were invited to open. Oh, my! What a treasure trove!

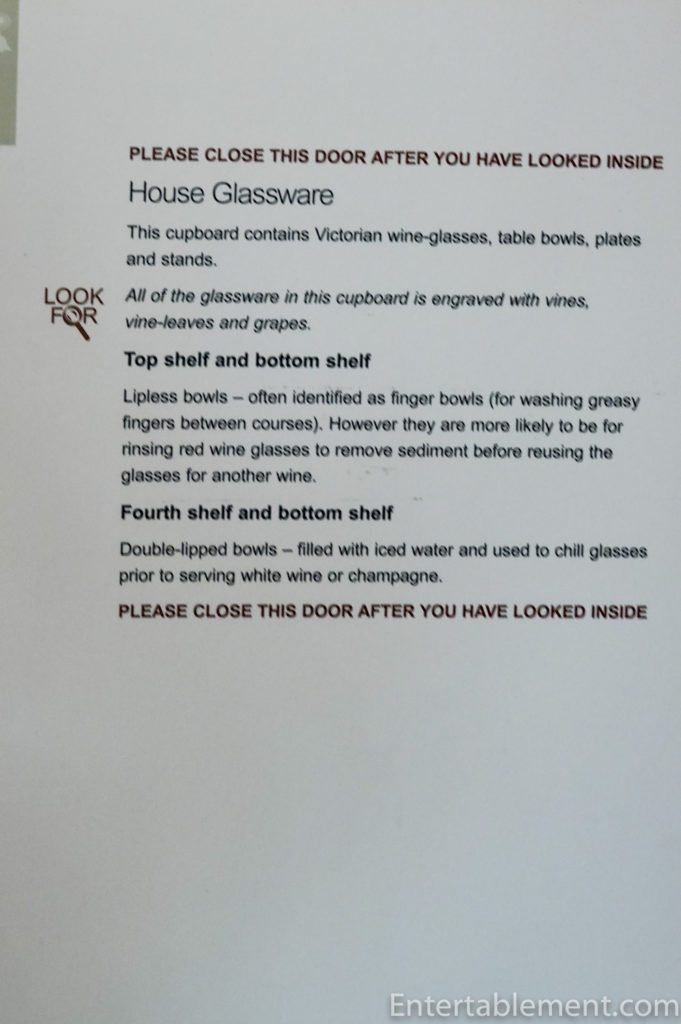

Shelves, upon shelves of glassware. As you can see, details on each cupboard’s contents were posted on the inside of the door, each with exhortations to PLEASE CLOSE THE DOOR AFTER YOU HAVE LOOKED INSIDE.

Then there were two full cupboards showing more of the Millefiori glassware. What we saw on the dining table upstairs was just a taste test, apparently.

I was feeling much better about the whole house experience and beginning to display a spring in my step when we came upon China Storage Nirvana. I thought the wooden doored cabinets were something but this was something else entirely. I was struck with severe Storage Envy.

I could have spent all day there. There was no detail on the contents, so I made do with recording as much as possible. The cobalt dessert service was exquisite. Each piece had a different flower. I particularly liked the primula on the square dish on the left.

The French blue outlines on these delicate floral sprays provided a striking contrast to the white body of the pieces.

Gold and white pieces towards the top. morphed to cobalt and gold, then finished with classic Imari toward the bottom of the cabinet.

This cabinet was filled with more playful wares, once you get past the crested service pieces on the top shelf.

This cabinet had some very unusual items. The textured set on the top shelf with the somewhat precariously balanced teapot and the landscape designs on the second shelf from the bottom stood out.

I love the sepia landscape set with green foliage and gilding.

Glenn had had about enough tableware gazing by then. so I reluctantly tore myself away and moved down the hall past the still room, the pastry room and the empty servant’s hall, ending up in the House Steward’s room. The House Steward was the most senior staff member within the house, and according to the laminated card on the table “was responsible for keeping accurate records of all household expenditure, appointing and organising all members of staff (including paying their wages) and overseeing the general operation of the House. This room is where the Steward would have undertaken his day to day duties, but it also functioned as a dining room for other senior servants.”

My first thought was, oh, like Carson, but not so, it turns out. Upon arriving home I looked up the difference between a butler and a house steward; Apparently the steward manages the property or entity while the butler is a manservant in charge of wines and liquors. So in Downton Abbey terms, Carson would have reported to the House Steward.

Glenn’s tableware reprieve was short-lived. My eye immediately travelled to the arched china displays at the far end of the room. There was information on these two sets. The one on the left is a Worcester Dinner service in the old Mosaik style, based on contemporary Imari patterns from Japan. It looks quite modern, doesn’t it? Perhaps it’s the colour block style that makes me think so.

The one on the right is a Coalport service in a traditional Imari style.

Next stop: the tea shop for a refreshing cuppa and a scone before exploring the gardens. I should have taken better pictures of the tables and chairs where we enjoyed our repast, but imagine small wrought iron tables and wicker chairs behind the balustrades at the base of the stairs in the centre of the photo. That little red speck in the bottom right of the shot is a person, to give you some sense of scale.

I was itching to get photos, so I left Glenn to enjoy his second cup of tea and made my way down the wide gravelled path to the edge of the parterre, just before the land drops away to the fields below. The terrace was designed by Charles Barry, the same architect who did the renovation in the 1840s for the 3rd Earl.

Although the house kept him busy, the terrace is the largest of his projects at Harewood, and from this angle, you can see how much was involved. We aren’t seeing the whole of it, though. The grass you see was installed in 1959 to replace Charles Barry’s original elaborate flowerbed designs because they were too labour-intensive to maintain.

The terrace is on two levels, with wide pathways at the base of the higher level, affording excellent views of the parterre, to the right in this shot.

It was restored in 1994. More than 20,000 plants and bulbs are planted in the parterre every year, displaying a mass of colour from spring to autumn. The classically symmetrical flowerbeds are outlined by clipped box hedging over a mile in length. That’s a LOT of clipping.

The stone statues in the fountains at either end of the parterre are part of Barry’s original design. They’re kind of a riff on traditional Egyptian sphinxes.

Walking back, I wanted to get a closer look at the arresting statue in the centre of the parterre, in what turned out to be a fountain (not running at the time).

The bronze figure is Orpheus by Astrid Zydower, and was added fairly recently, in 1984 after the original statue collapsed.

I quite liked it!

I would imagine the original statue was along the lines of the ones to either side, as shown below.

Ah – you can just see the tables where we enjoyed our tea over there on the right.

Given the massive scale of the house and terrace, it’s easy to overlook how many perennials, tender exotics, roses and climbing plants populate the herbaceous borders. It was spring (obviously) when these were taken; I imagine all of those tulip bulbs are hauled up and the beds replanted with annuals later in the season.

The weeding, trimming, and deadheading must be endless.

Earlier this fall, I went to see the Downton Abbey movie and though they made reference to Harewood House, it didn’t actually register with me that this was the house with the Horrid Craft Show. When we got to the terrace scene below, where Tom is dancing with Lucy Smith (photo courtesy of Taos News), something struck a chord and I struggled to place the surroundings.

At first, I thought it was Cliveden. It looks very similar, doesn’t it? It has the same kind of balustrade on the extensive terrace.

But the view from the terrace is very different at Cliveden, with manicured lawns and no lake in view (though there is one way down below, out of sight of this shot, which played an important role in the infamous Profumo Affair).

Then my addled brain began to knit it all together. Hmm. Harewood House – didn’t we visit there? Fairly recently? I must have pictures if we did. Oh yes! And here we are, in the middle of the blog. Back at Harewood House and continuing our explorations, we left the terrace, and went to find the Penguin House. Because what estate is complete without penguins?

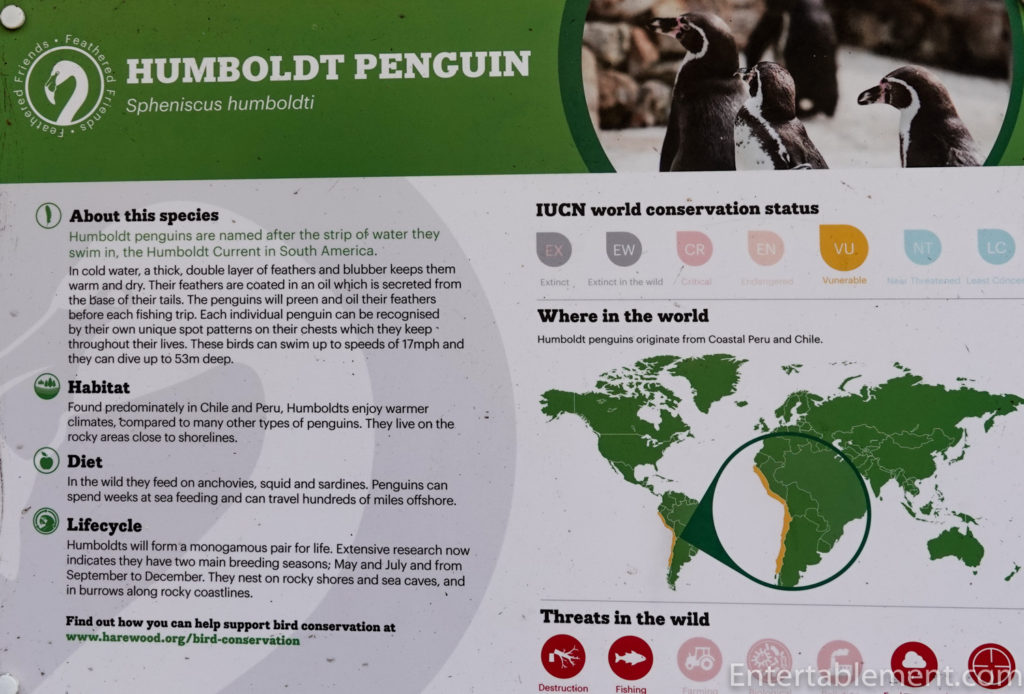

Not just any penguins, mind you, but Humboldt Penguins!

They’re South American, and you are welcome to read more about them from the sign which was posted near their enclosure.

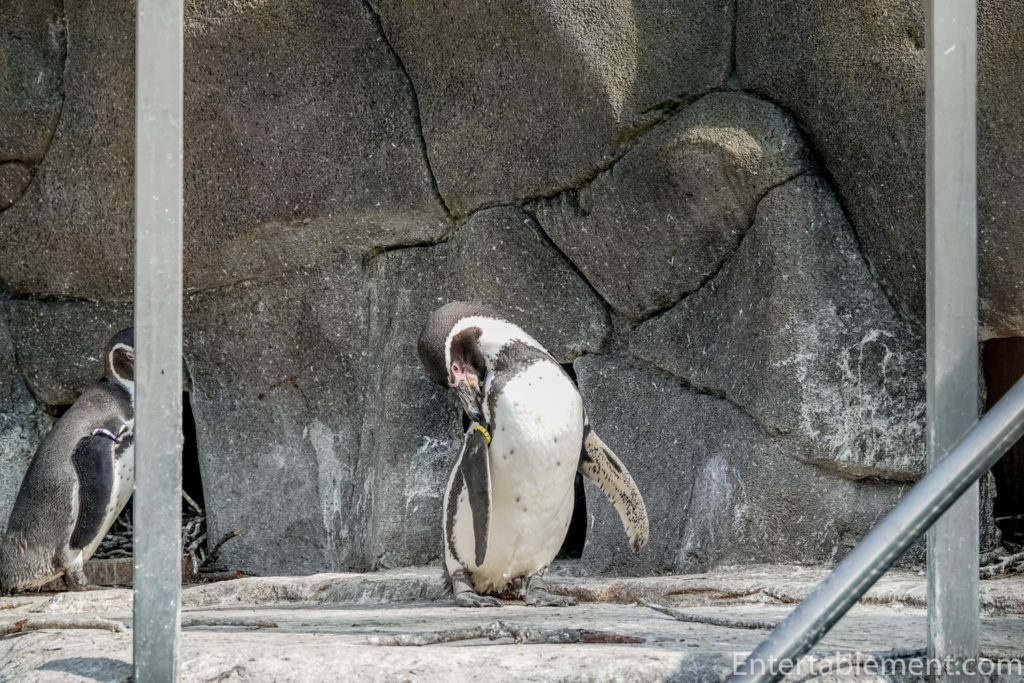

They seemed happy enough, cleaning and preening.

The penguin enclosure is just the other side of another building set aside as a cafe, though it was deserted that day.

The gardens at Harewood House are extensive and include a Bird Garden with the aforementioned penguins, Chilean Flamingos, Burrowing Owls, Palm Cockatoos, and Macaws.

Also, this guy, who reminded me of the Road Runner. I’m sure he has an official name, but I didn’t catch it. He mumbled.

The Bird Garden is at the edge of a small lake in the back of the property, down a very steep and long hill. We learned that this Heron was one of three who live at the lake.

We were surprised to see a small ferry boat and curious as to its purpose.

It went back and forth every 5 minutes or so to the island I mentioned earlier, where the walled Kitchen Garden is located. There is a fairly large house on the island where the gardener originally lived.

As with the rest of Harewood, the Kitchen Garden is immense.

Largely unplanted today, it’s nonetheless impressive.

Back across the waterway, we skipped a visit to the Himalayan Garden, the Archery Border, and the West Garden, One can only do so much.

We made our way back to the car and started to drive toward the exit, largely satisfied with our visit, in spite of the Craft Show Debacle. Before we reached the gate, however, we noticed this church and got out to have a look.

I’m accustomed to small chapels attached to these large Estate homes, but this church was much bigger than one would expect on a private estate.

It was bone-chillingly cold, but welcoming despite that.

Though deserted, there was very good signage, and we had just enough energy left to give it our attention. The church has its roots in the medieval past of Harewood. It was built around 1410 by Elizabeth and Sibyl de Aldeburgh, who were the daughters and joint-heiresses of Sir William de Aldeburgh of nearby Harewood Castle. What? Wait… there’s a castle? How could I have missed that? Here is a screenshot from the website. Something else I need to see when we return.

Very briefly, it seems that nearby Harewood Castle came about in 1366 when Sir William de Aldeburgh was granted a ‘license to crenellate’ (aka, fortify), shortly after he became lord of the manor of Harewood. He demolished an earlier building on the site, replacing it with a structure designed to strike a balance between security and comfort: a “mixture of convenience and magnificence”, more accurately described as a fortified Tower House than a castle. It’s easy to forget how necessary it was to defend against violent invaders in the fourteenth century.

De Aldeburgh’s only son died in 1391, leaving no male heir; the estate passed to his two daughters, Sybil and Elizabeth. They and their respective husbands Sir William Ryther and Sir Richard Redmayne shared occupation of the castle, either simultaneously or through a kind of 14th-century time-share (presumably without the pressured sales portion), and this arrangement carried on between the two families for more than 200 years. We could all take lessons in managing family conflicts from this group. Think of the tensions a simple family cottage entails! Can you imagine sharing a primary residence over multiple generations (inlaws, outlaws, exlaws) for 200 years?

Fast forward to 1657. Harewood and the nearby Gawthorpe estates (inherited through the marriage of one of Elizabeth’s descendants into the Gascoigne family, who owned Gawthorpe) had been amalgamated and were bought by Sir John Cutler. This family clearly knew how to accumulate real estate, though perhaps not how to keep it in the best order. By that time, the castle was falling down and uninhabitable. What is unknown is why it was left to fall to pieces. Too old fashioned? Too expensive, uncomfortable or unmanageable? It’s a mystery!

But back to the church. I’ll skip a lot of the history in the interests of time.

Its main claim to fame is the alabaster carved effigies. (I do love a good, gruesome effigy). They’re reputed to be some of the finest surviving examples of carved alabaster in all of England.

The figures are dressed in typical costumes of nobles of the day: men in armour and women in elaborate garments with jewels and headdresses. Though if the choice was left to me, I think I’d pick something a good deal more comfortable in which to snuggle down for my eternal sleep.

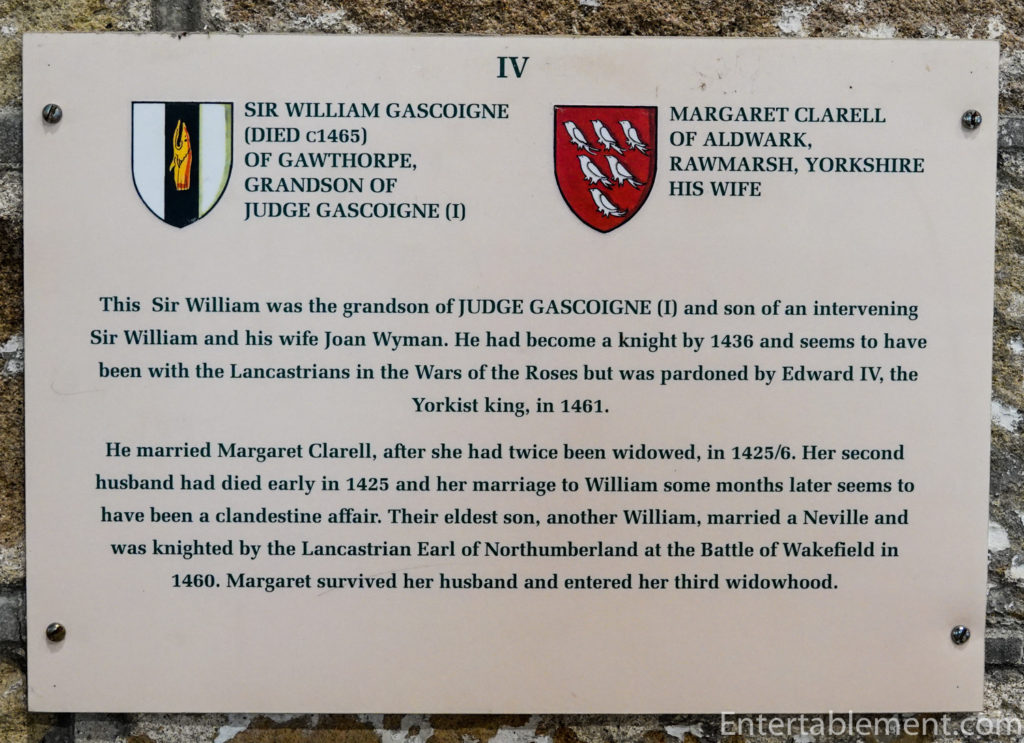

There are three couples buried in the tombs, and I’m not entirely sure which is which. but will guess that the oldest tombs are closest to the front.

In that case, these would be Sir William Gascogne and his first wife, Elizabeth Mowbray.

I can’t quite figure out why the number of plaques exceeds the number of tombs with effigies. And it seems that I didn’t get photos of all the plaques. Oh well, let’s just admire (if admire is the right word) the detailed carving.

Having small dogs nestled into the skirts was a common feature.

However, the little angel’s head popping up to the left there is quite creepy.

To say nothing of that clinging little hand. Ghastly.

Is that a sheep’s head?

The family seems to have had a typically complex history, trying to stay on the right side of whatever ruling power was battling it out at the time, and dealing with remarriage after death through conflict or disease. One Margaret Clarell of Aldwark seems to have gone through a lot of husbands in fairly short order. Agatha Christie would have had a ball with that one.

The carving on the base of the tombs was lavishly detailed.

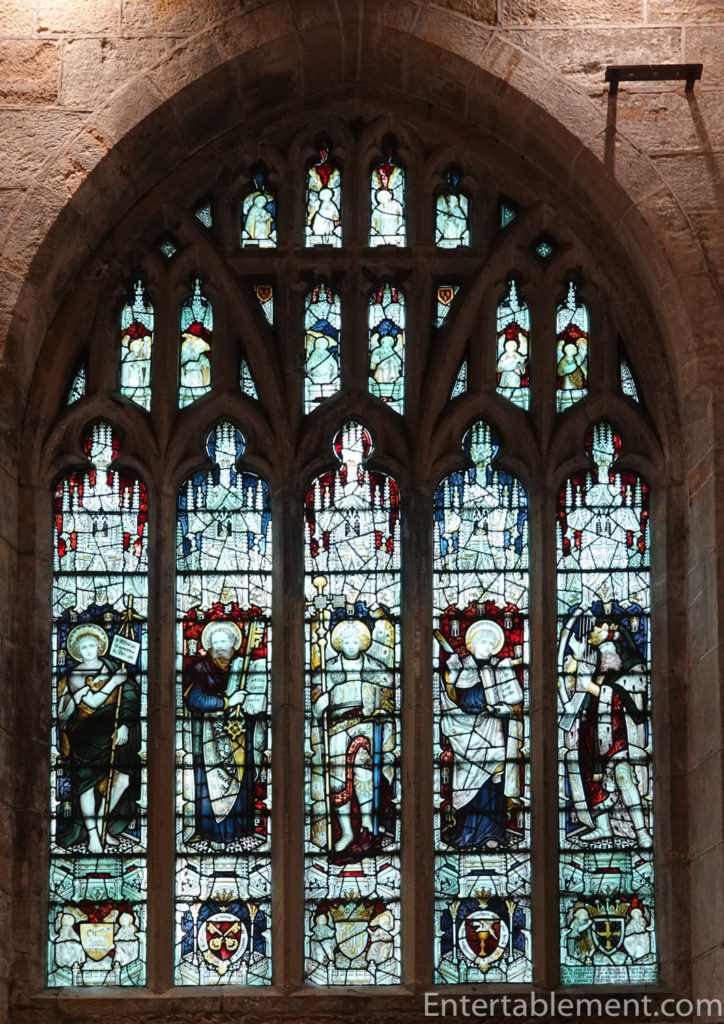

The stained glass is of a later date, I understand, likely installed by the indefatigable George Gilbert Scott, who seems to have been the Lancelot Capability Brown of Victorian Church Restoration – here, there and everywhere.

The baptismal font predates the church. It’s Norman, so 11th century.

I loved the Noah’s Ark carving.

And the winged oxen.

Now we truly were done for the day. We were somewhat chilled from our longer than expected visit to the church, and we still had a two-hour drive ahead of us to return to our self-catering cottage in Derbyshire. I can’t wait to go back and see the house at another season (they do a Christmas Market here, too) explore the gardens more fully and have a good look at the castle ruins. Another time!

Thanks for joining me on this visit.

Happy New to everyone! May 2020 be filled with peace, joy, and prosperity for all.

I’m sharing this post with Between Naps on the Porch.

WOW – What a fabulous post! I could look at this house all day! I love the way you tell the history and other fun info. And how cool is that ruined castle?! Not to mention the china storage – ahh be still my heart! Thanks for the fabulous trip!

Happy New Year Helen – see you back here in 2020! ❤

Thanks, Barb. It’s right up there with my favorite houses. Not only does it have three libraries (who could resist that?), but the china storage…enough said! Happy New Year, Barb! I hope it’s wonderful for you.

Loved reading this blog. So much to take in but found one photo more interesting than the other – dishes, crystal etc. Wouldn’t you just love all that storage space? And wow, those copper pots seemed too pretty to use. Must be a full time job keeping them shining. And the gardens, not too shabby either. A great history read!! Really enjoyed this. Happy New Year and we’ll see you soon!✨

Happy New Year, Maura! I can’t believe we are starting another new decade. Remember when Y2K had us all worrying about planes falling out of the sky? Seems like yesterday. Houses like Harewood help put our trivial, short, little lives into perspective, I find. It’s all very grounding, despite the grandeur. See you soon! Xo

Amazing photos of an amazing place. That kitchen and all that copper–just wow.

Wasn’t the copper something? Can you imagine keeping all of it clean with just vinegar and salt?

Dear Helen,

Thanks for your heroic effort in putting this together. So much to look at; so much beauty. I’d kill for the millefiori, and the muguets des bois, and the Imari, and the copper…and…and…and. I’ll work my way towards those 20,000 flowers–we’re up to about 400 now, lol. This isn’t a house I was familiar with, and I haven’t yet seen the film (I’ll leave that for some airline trip), but I’ll look forward to spotting it.

Finally had festive lunch on a terrace in the winter wonderland yesterday…surprisingly warm with nary a cloud in the sky and deep powder all round!

Best wishes for happiness in the New Year (and Happy Hogmanay). Don’t forget health, which is the most important thing you own (my grandmother’s admonition, sorry).

My very best to you, Beatrice for a Happy, Healthy and Joyful New Year. (that should keep everyone happy, even our Grandmothers!)

I look forward to many more travel and tableware adventures this coming year.

Enjoy your winter wonderland; it sounds magical. There is something very special about being surrounded with fluffy snow, while still being warm enough to enjoy a repast in the sunshine.

Best,

Helen

The entire post is spectacular, but I’m seriously still chuckling over the term ‘storage envy’…lol. For those of us with dishes (up our…ahems….) this is always a problem. I have two complete settings of Royal Copenhagen porcelain and a full tea service….that my tiny house can’t display all of, so storage envy is a full time occupation here, LOL! Gorgeous trip and photos!

I’m so glad you enjoyed it, Sandi! I loved the house. I’ve seen some pretty good storage in these big old estates, but this one really took the cake. May 2020 help us overcome our Storage Envy. Happy New Year!

Oh my. That storage with beautiful dishes is like dying and going to dish heaven.

Somewhere packed away, I believe I have a piece of that Lily of the Valley china.

Now that’s exciting, Annie! If you ever get a chance to dig out the china, please let us know what the pattern is. Wouldn’t you just love to have that much storage (the dishes weren’t bad, either). Hehe.

I loved this post! Thank you so much for showing the kitchen! I thought Biltmore was impressive but this place is astonishing. Yeah, I’d love to have that millefiore set, too.

It’s gorgeous in real life, too. The gold just glows.