“Where shall we go today?” was the question. Our three weeks in England were almost at an end and we – Glenn, that is – had done a lot of driving already, so I was hesitant to suggest Harewood House, almost two hours from our self-catering cottage in Derbyshire. He was game, and off we went. A drive for him, a nap for me, and we soon found ourselves walking up the drive to the house from the carpark. And stopped dead.

‘What is that?” I said, dumbfounded, looking at the large box-like structure sitting directly in front of the main doors. “We Are What We Make” it proclaimed. My heart sank. Was this a protest of some sort? Surely it couldn’t be intentional, as in, invited by the home owners. Oh yes it was! Worse was to follow.

Upon entering front door, we were greeted by another out-of-place structure with large, intrusive, ugly printing. Impossible to ignore, with no hope of editing the thing out of any photographs, it sat there large as life and twice as hideous in Robert Adam’s famed entrance hall. Yes, the exhibit was throughout the house, the docent informed us, maintaining a carefully neutral expression on her face.

The intrusion, we learned, was Harewood House’s first (and if I were to have a say, its last) craft and design show entitled Useful/Beautiful: Why Craft Matters, an exhibition exploring the relevance of craft in today’s digital age. The show had opened about a month earlier and showcased the work of 26 craftspeople based in the UK, from small independents working in solo practices to companies hand-making products on an industrial scale.

To say I was disappointed didn’t begin to cover it.

Glenn and I exchanged glances. What to do? Press on, or come back another day? We had driven for two hours, let’s try and make the best of it, we decided. Pay the damned entrance fee, see the house and if it’s as beautiful as it looks from here, we could come back another time when we could actually get decent pictures.

Seething, I confined my photography to the features we could capture without the presence of the signage, or whatever else was to present itself. It’s the details that matter, I kept muttering to myself in an effort to swallow my chagrin. And the details were stunning. Adam’s exquisite plasterwork had a wonderfully soothing effect on my very bad temper. The unusual colour scheme of blue-grey walls, with deep burgundy, beige, pale blue and white accents was striking.

As a result, you are about to see a rather truncated tour of a truly marvellous house. We managed to salvage the day, and I will definitely return when the house is not infested with a nasty exhibit. By and large, we were able to work around the displays, with the exception of the Galley, where I threw up my hands. There was no getting by that one. Stay tuned.

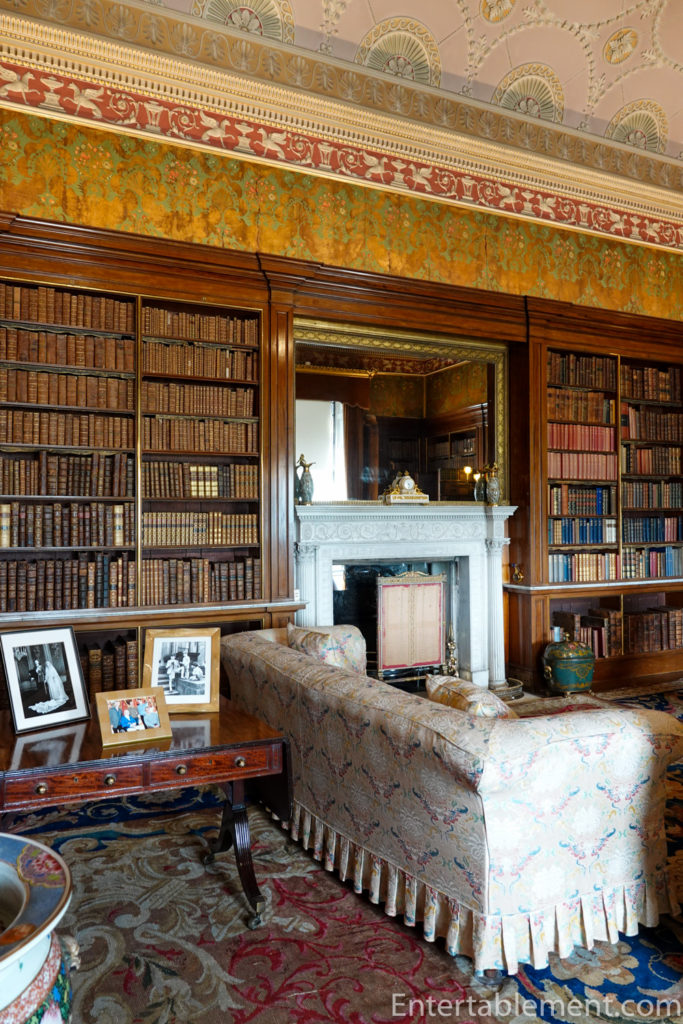

Onward. This is the Old Library, named to distinguish it from The Main Library and The Spanish Library. You’ve gotta love a house that has three libraries!

Harewood House (pronounced HAR-wood) was designed by the famous architects John Carr and Robert Adam, and built between 1759 and 1771 for wealthy plantation and slave owner Edwin Lascelles, 1st Baron Harewood.

The landscape was designed, perhaps inevitably, by Lancelot “Capability” Brown. Judging by the number of country houses for which that man designed the gardens, he could scarcely have spent a night in his own bed.

Most recently, Harewood House starred in the new Downton Abbey film. I won’t spoil the plot for readers who haven’t yet seen the movie. Suffice to say that several scenes are filmed here, with Harewood House playing itself, as home to Princess Mary and her husband, Henry Lascelles, the 6th Earl of Harewood

There was clearly lots to admire in the house and the challenge of finding suitable angles and approaches to evade the (frankly often hideous) craft exhibits got my creative juices flowing.

Doesn’t the plasterwork remind you of Syon Park, which we visited earlier this year? Also by Robert Adam.

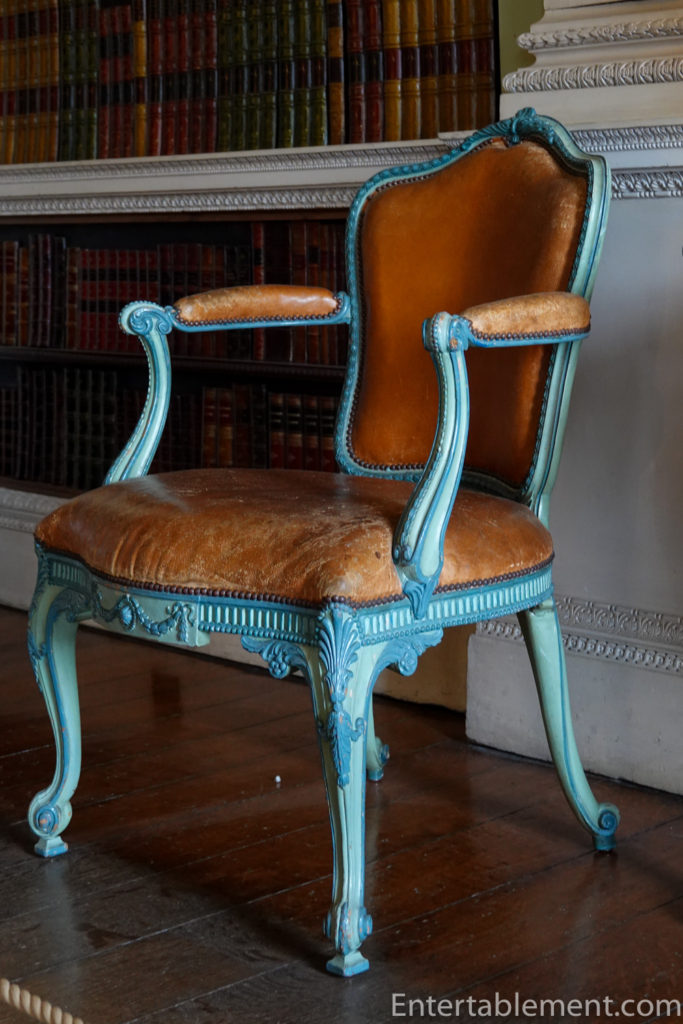

These chairs, though the colours would lead one to believe they’re modern, are original to the design; Adam chose the vivid paint to stand out against all the books in the room. Again, an interesting combination with the mint green walls.

The only shot I could get in the China Room was the beautiful Wedgwood-like combination of pellucid blue and striking white. By all means, check out Wikipedia’s page to see what it should look like or the website for the Harewood House Trust. Really, wrecking the china room with stupid craft displays. Grrr. Mutter, mutter. But hang in, dear reader – the china cabinets in the basement of the house are to die for.

Let’s go back to Princess Mary for a bit because we are about to see her Dressing Room. Mary was the third child and only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary. Formally known as Mary, Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood, she was the great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria, for whom she was named (among others). She had four names: Victoria Alexandra Alice Mary. Translating that one more step, she was the paternal aunt of the current monarch, Queen Elizabeth II.

Aha, you’re saying. Then she was sister to both Edward VIII (who abdicated to marry the twice-divorced American, Wallace Simpson) and King George VI, Queen Elizabeth’s father. Indeed. And apparently she was very close to David, as Edward VIII was known to his family. She didn’t attend the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II as a silent protest that her brother David wasn’t invited. She gave “ill health” as the official reason.

Thus quite an important personage, though I’d never really registered her existence until Julian Fellowes brought her into the Downton Abbey movie. I must say, they did an excellent casting job. Here is the photo of the real Princess Mary (I’ve pinched it from Wikipedia).

Here is Kate Phillips, who plays Princess Mary in the movie (photo from the Telegraph). Well done, don’t you think?

Ok – back to her lovely dressing room, which is curved, with a domed ceiling and lighted display cabinets built into the walls. Apparently, Princess Mary was a big collector of jewellery, though she could scarcely have competed with her mother, Queen Mary who was known as a Magpie of no uncommon order. One of Queen Mary’s greatest acquisitions was the Cullinan Diamond, the largest rough-cut diamond ever found at over 3,000 carats. It was broken down into many stones of various cuts and sizes. The largest is named Cullinan I or the Great Star of Africa and weighs in at 530 carats. It’s the biggest clear cut diamond in the world, and is mounted in the head of the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross. The second-largest is Cullinan II or the Second Star of Africa at a comparatively paltry 317 carats. It’s mounted in the Imperial State Crown. Queen Elizabeth inherited several other of the major diamonds from the original gigantistone weighing a total of 208 carats. She jokingly refers to them as “Granny’s chips”.

This cabinet shows some of Princess Mary’s collection of amber, rose quartz and jade,

Princess Mary’s initial is worked in delicate plaster in a few places on the walls.

I’d be happy in this dressing room. Light, airy, with a restful colour scheme.

The bathroom is adjacent. The exhibitors didn’t muck this one up too badly – just a display of perfume bottles on the counter, which were quite nice.

The ornate clock by Sarton of Liège adds a bit of glam to an otherwise quite restrained decor.

From here we went into the East Bedroom, which one would not called restrained. But I loved it!

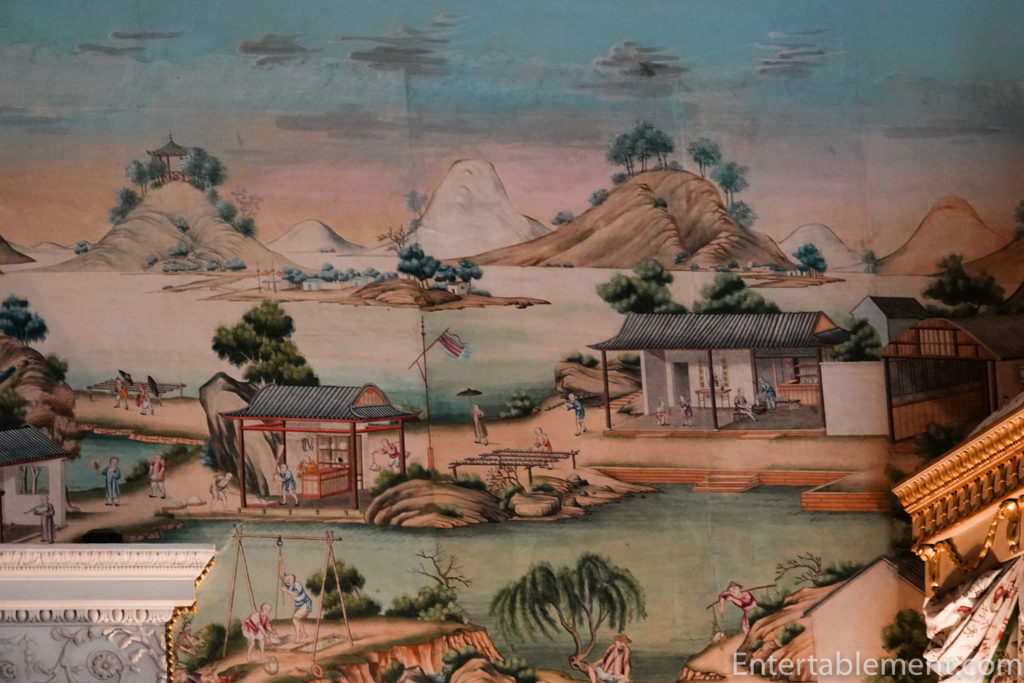

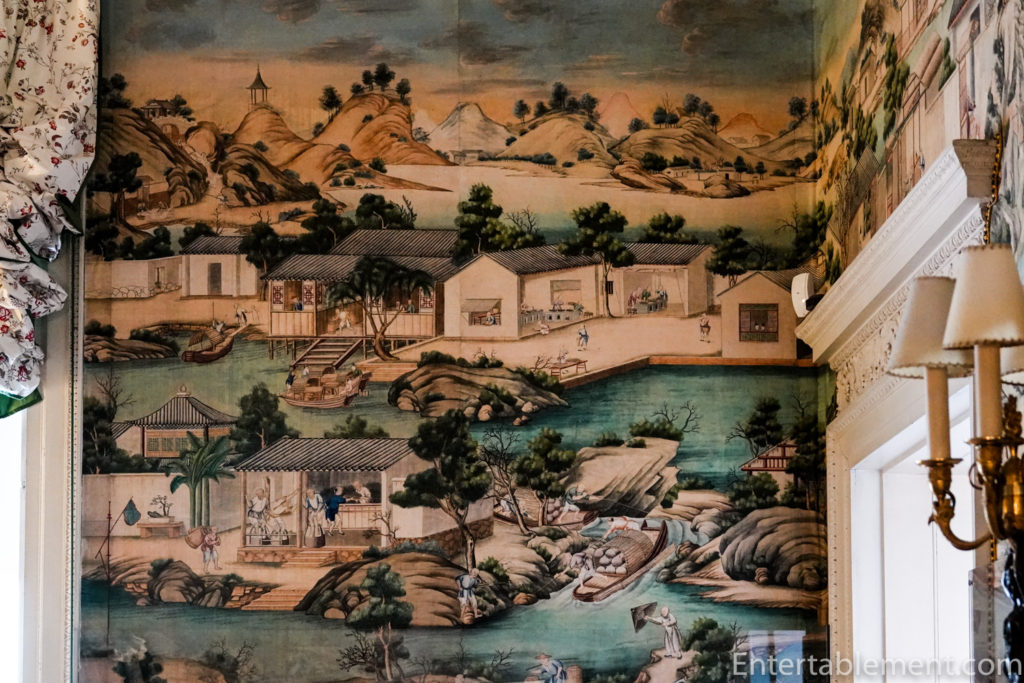

It was originally Edwin Lascelles’ bedroom; the ceiling and frieze were designed by Robert Adam. The amazing wallpaper is not original to this room. In 1769, Chippendale’s workers hung it in the Chintz Bedroom on the first floor (which is not open to the public).

Apparently it didn’t suit everyone (?!) and sometime in the first part of the 19th century, it was cut from the walls, rolled up in linen and put away in an outbuilding, where it lay for nearly 200 years. Increcible that it survived for so long, and in nearly perfect condition.

Naturally, the light was fairly dim to protect the paper, so the photos aren’t the greatest, but you get the idea. The poor paper has been through enough…

On to the State Bedroom. Every country house of note in the 18th century had a State Bedroom, though used very infrequently; they were reserved only for very important visitors. This room was used by young Princess Victoria in 1835 before her coronation and the Grand Duke Nicholas of Russia in 1816. Important indeed!

At first, I couldn’t figure out why they’d let the bedcovering trail onto the floor. Then I realized it was part of the Craft exhibit. Ok – not too bad. I assume the regular bedcoverings are underneath, or were removed for safekeeping.

The bed is by Chippendale, and one of his true masterpieces. Like the Chinese wallpaper in the East bedroom, it also spent some time mouldering in ignominous isolation. During the Victorian period it was dismantled and put into storage and half forgotten until sometime in the 1970s. (Hey – look what I found, George…)

Restoration didn’t begin until 1999, when funding was secured. Though much of the ornately carved and painted decoration had been carefully put away, time had taken its toll and lots was missing, including the instructions for assembly (where are those IKEA diagrams when you need them?) Nobody knew exactly what the bed was supposed to look like. Chippendale never made another one like it and there were no recorded images giving clues to the bed’s appearance. So the furniture historians and craftsman who worked on it used their expertise and imagination. Voila!

Directing my gaze upwards (something I was spending a lot of time doing that day), another very striking combination of deep and pastel colours in the intricate plasterwork. The restorers used the colours from the ceiling to inform their selection for the bed hangings.

I love the green, with its timeless combination of soft peach.The accents of very dark green and near-coral make it pop.

The Spanish Library was next. It was originally the State Dressing Room as it’s en-suite with the State Bedroom next door.

It was transformed into a Victorian library in the 1840s as part of a major renovation by Sir Charles Barry under the direction of the extremely prolific Henry Lascelles, 3rd Earl of Harewood, who, with his wife, presumably, had thirteen children.

I couldn’t spot the two “secret” doors disguised as bookshelves. I’m told there is one leading to the State Bedroom and one in the far corner to the left of the fireplace.

See the photo on the table behind the chesterfield? It’s is of Princess Mary and her husband, the 6th Earl of Harewood, on their wedding day on February 28, 1922. The bride was 24 and had been causing her family great angst due to her “old maid status” – how times have changed. The groom was 39. Their wedding was held at Westminster Abbey and was the first of what we have come to expect of weddings involving major Royals: large crowds along the route between Buckingham Palace and the abbey, and the appearance of the couple on the palace balcony. The ceremony was the first royal wedding to be covered in fashion magazines such as Vogue. Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother was a bridesmaid, though she was Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon at the time, busily fending off advances from Bertie, the Duke of York (later King George VI).

Not sure who these little guys are. Princess Mary had only two sons. Prince Charles, Andrew and Edward, perhaps? Seems about the right age spread.

The room is named for the 17th-century wall-covering of Spanish leather, which you can see between the top of the bookcases and the plaster frieze. Interestingly, recent research has shown that the leather is actually from the Netherlands. The room has not been renamed!

We’re now on to the Main Library, which was known as the Saloon in the 18th century. One can understand why they have three libraries. They contain more than 11,000 books in total, dating from the 16th century to the late 20th. The requisite cataloging and conservation of such a collection is a huge and ongoing project.

Note the Victorian mahogany bookcases with brass trims and a marble chair rail. It’s been the main “living room” of the house since Charles Barry’s renovation. Though weighty, they blend beautifully with the original Robert Adam ceiling, chimneypieces and plaster overmantels with their round, sculptured reliefs,

Further along, we enter the Yellow Drawing Room. Please avert your gaze from the carpet on the floor. It’s part of the craft show, as described:

“Displayed in the house’s drawing room, British designer Max Lamb has created a 24-square-metre rug made up of interconnecting amoebic shapes (????!!!!). The rug was made using 100 kilograms of leftover Yorkshire wool sourced from a local textile factory and dyed using natural materials that Lamb harvested himself from the Harewood estate. Working with the estate’s head gardener Trevor Nicholson, Lamb sourced materials such as oak and birch bark, alder cones, eucalyptus leaves and ivy berries to dye the wool. The wool was then tufted into rugs by Trendy Tuft of Cleckheaton in West Yorkshire.”

I see. We must imagine instead the star and circle of the carpet that belongs in the room, which I’m told echo the beautiful ceilings without directly copying the pattern.

The two oval mirrors (one at each side of the room) are by Thomas Chippendale, as is the commode below the one oval mirror you can see in this picture. The third mirror over the fireplace is by Chippendale’s son, also called Thomas, who completed the Harewood commission after his father’s death in 1779.

The lozenges in the frieze running round the cornice contain plaques with cupids riding sea-horses, a motif that is repeated above the doors.

It’s one of Robert Adam’s hallmarks – consistency of motif in the design.

While the room began its life as yellow, it has had several incarnations over the years. During the 19th and 20th centuries, it was known as the Rose Drawing Room. A lucky paint scrape uncovered during the 1990’s restoration returned the room to its 18th century design.

The gallery is where I almost lost it. Seriously. I could bring myself to take only one picture of this room. A sympathetic docent noticed my expression and said, sotte voce, that I was not alone in my dismay. “We can’t say anything”, she whispered. “But isn’t it dreadful?”

Apparently, London designer Faye Toogood was tasked (how I loathe the word “tasked”) with “filling the 76-foot gallery space that extends across the whole west end of the house. Toogood selected 30 pieces from her extensive archive of fashion, product and furniture design to display across a huge industrial steel shelving unit that ran the length of the space. Each of the pieces in the showcase were made by a network of British craft people.”

Enough said.

Happily for everyone, right next door was the dining room. While I won’t go so far as to say “all was forgiven”, it went a long way towards restoring my good humour. My gaze went immediately to the table setting. Oh my word! Gorgeous. Pre-1853 Baccarat Millefleur gilded dessert service combined with part of a 15 figure Sèvres centrepiece set. I didn’t even notice if the craft people had anything in the room.

Anxious as I am to move onto the tableware, let’s pause and take in the room for a minute, because it’s been through a lot. The 1840s renovation to the house was most radical here in the State Dining Room. Sir Charles Barry raised the ceiling and changed the shape of the room. Nothing of Robert Adam’s original remains. Clean sweep, other than the Chippendale furniture, and that’s quite something. A beautiful set of dining room chairs, two gorgeous side-tables, pedestals topped with urns and a wine cooler (that oval thing that looks like an ottoman under the sideboard). These are held to be among Chippendale’s finest pieces, and were both beautiful and useful (though that was William Morris’ maxim, not Chippendale’s). The wine coolers and urns are lined with lead and the pedestals conceal racks to keep plates warm. Genius.

The chimneypiece you see below is not Adam’s original. It vanished without trace in Barry’s alterations, which began the game of Musical Renovation Fireplaces. Barry brought in a fireplace that was originally in the Gallery and the Gallery received two new-at-the-time Victorian ones. During the 1990s restoration, the Gallery was restored to Adam’s original configuration and the two Victorian fireplaces were removed (fate not disclosed). The Gallery regained its original one that Barry had moved to the Dining Room, and one of the right period was installed here. Music stops. All chairs occupied.

To the tableware! Millefiori is the technique used to design this service: “mille” (thousand) and “fiore” (flowers), employing differently coloured thin glass rods which are heated until they fuse together. The rod is then elongated and sliced thinly to be applied to hot blown glassware.

The service was originally acquired by the 11th Duke of Hamilton for his London townhouse. It’s had an illustrious career, this glassware. It then travelled to Hamilton Palace in Scotland, considered to be one of the grandest houses in Britain in its day; its collection was said to rival that of royal family.

Alas, its day passed, and the property no longer exists. Happily for us, however, the set was later acquired by the 6th Earl of Harewood and we see it here! Spoiler alert: there’s lots more of it downstairs in the china storage area.

On to the Sèvres set. It was originally designed by the architect Louis-Gustave Taraval for the Sèvres factory in 1773. The figures with the baskets on their heads were used for fruits and sweetmeats, which formed part of the dessert course.

This centre group depicts the triumph of Bacchus.

“Biscuit”, or unglazed porcelain figures, were fashionable in the 1750s and supplanted the hydroscopic sugar table decorations, which had the dismaying tendency to melt into a sticky mess at just the wrong moment. And we think the modern host/hostess has a lot to contend with worrying about how their dessserts will hold up.

This set was made in the early 20th centry and was presented as a wedding present from the French Government to Princess Mary and her husband.

The bases have their printed crests, combining the arms of the bride and groom (when I first read that I was thinking about physical arms, not coats of arms). It took me a minute to recognize them.

One last look at the dining room and we are finished the tour of the main floor.

And here we will pause. Like I did for Syon Park, I’ve divided this into two posts. Part II will feature the Downstairs portion with the kitchens and all the luscious china storage, the gardens and terrace, a trip on a little ferry across to the island that comprises the kitchen gardens and original succession houses. We will also visit All Saints Church, which featured prominently in the lives of the two estates that existed before Harewood House came to be built: Harewood Castle and Gawthorpe Hall. And a special treat – penguins. I kid you not.

Bye for now!

I’m sharing this post with Between Naps on the Porch.

Thank you so much. So beautiful and very informative!

You’re most welcome! Some of the best parts of travelling are reliving the photos afterwards.

Harewood House is indeed very elegant and beautiful (with the exclusion of the rather awful craft displays which will hopefully be removed shortly). You did an admirable job with photographing the beautiful and ignoring that which is not part of the house on a permanent basis…I feel your total disappointment! My great-grandparents were servants (gamekeeper and house maid) at this home in the 1860’s before moving on to employment at Sandringham House in Norfolk. Lovely to see this and thank you for sharing.

Alayne, what a marvellous connection to the house. Have you ever visited Sandringham? I understand Prince Phillip lives there now at Wood Farm, so he can get some peace and quiet, spending his time painting, reading and entertaining.

My grandfather lived in nearby Harrogate and visited Harewood House often. My sister remembered that connection and urged me to visit the house on our last visit to England. In addition to his career in the British military, our grandfather was an amateur painter and loved the grounds.

You did a magnificent job of photographing so many exquisite details in this beautiful house in spite of that steel structure. The house must have made a fortune to allow this craft show which helps with the upkeep of these English landmarks. Thanks for another history lesson. Please don’t test me on these dates when I see you!

Haha! No test, under any circumstances. I agree that they must do what’s needed for upkeep, but Lordy, let’s have something less intrusive next time.

See you soon!

What a work of art…and your photos did a wonderful justice to its beauty! Thank you so much for sharing all this, I will dream of painted plaster motifs, for sure. Side note—I was an artist/ceramics and had I been asked to display there I would have declined, for the venue is just not appropriate for contemporary crafts!

Thanks, Sandi.

You’ve got an interesting perspective as an artist & ceramics person. You’re so right about the suitability of the venue relative to the contemporary nature of the show. It was jarring.

What a wonderful post Helen! I laughed, I cried, I felt your pain! But I sincerely applaud your tenacity! 🙂 It’s a gorgeous place, craft show not withstanding! Thanks for taking us along – I can’t wait for Part II!

Thanks, Barbara. It is indeed a beautiful place and I’m looking forward to returning at some point. Travel is all about the adventure – some good, so not so good! If it was all smooth we’d have no stories to tell – that’s for sure.

Part II is in the works. 🙂

I loved your post. It was better than many “house” books and articles I have read. One of my very favorite thing to do when traveling! At least you got see it. Sadly, Chatsworth was closed when I went. My daughter is a ceramics artist. I could see her work being in this setting even with her contemporary style. Who ever thought the steel shelving was a good idea should be banned from future exhibit shows! The fault of the display was the curator of the exhibit. I have seen contemporary exhibits in beautiful classical homes. The intention was old and new fuse together. It can be done! Too bad it wasn’t done here. I’m glad you persevered and took the photos. Thank you so much! PS. what kind of camera and lens did you used?

Chatsworth does a really good job incorporating exhibits. I’ve been there several times and they’ve frequently had a major show going – always tasteful and in keeping with the setting. I don’t know what was up with the organizers at Harewood House.

I use a Sony Rx10 with a Zeiss 24/600 lens for traveling and usually use a Nikon 7100 with a 24/200 for table settings.

Thanks for stopping in!