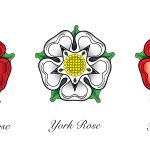

The Tudor Period (1485–1603) was a transformative era in British history, marked by political consolidation, religious upheaval, and significant cultural and economic shifts. It began when Henry VII married Elizabeth of York, ending the Wars of the Roses, uniting the houses of York (white rose) and Lancaster (red rose), and establishing England as a powerful nation.

The Tudor dynasty’s five sovereigns (six if you include the nine-day queen, Lady Jane Grey) feature among the most colourful and notable kings and queens in history. Henry VII, his son, Henry VIII, and his three children, Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, ruled for 118 eventful years.

The Family of Henry VIII (c. 1545), by an unknown artist. Left to right: “Mother Jak”, Lady Mary, Prince Edward, Henry VIII, Jane Seymour (posthumous), Lady Elizabeth and Will Somers. Oil on canvas, 141 x 355 cm. Hampton Court Palace, East Molesey, Surrey

Political Transformation and Monarchical Power

The Tudors were absolute monarchs who significantly centralized power. Henry VII, the dynasty’s founder, secured the throne after defeating Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field, ending decades of civil war. His marriage to Elizabeth of York united the warring houses of Lancaster and York, establishing a sense of stability. His son, Henry VIII, fundamentally reshaped England’s religious and political landscape by breaking from the Roman Catholic Church and establishing the Church of England, primarily to secure an annulment from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. This break, however, had lasting consequences, sparking the English Reformation and initiating widespread changes in governance, religious practices, and wealth distribution. The Dissolution of the Monasteries destroyed 800 religious communities and redirected their considerable wealth to the Crown and nobility, bolstering royal power.

Parliament’s role expanded under the Tudors, particularly as monarchs conceded to seeking legislative approval for religious reforms and taxation (a pleasant change). At the same time, the monarchy sought to promote the influence of a new class of gentry who were more loyal to the Crown and diminished the power of the traditional nobility.

Economic Growth and Social Change

The population of England grew rapidly during the Tudor period, from approximately 2.3 million in 1520 to around 4 million by the early 1600s, spurring economic development, particularly in agriculture and trade. The wool industry flourished, and London became an increasingly dominant centre of commerce. With the increase in population, however, economic challenges emerged. Wages declined due to abundant labour, and the enclosure of common lands for grazing sheep led to riots lasting from the 1530s to the 1640s. Further, inflation, exacerbated by Henry VIII’s fondness for debasing the currency, increased economic difficulties and heightened social unrest.

Social hierarchy remained rigid, with a clearly defined class structure. The monarchy and nobility occupied the upper echelons, while the gentry—wealthy landowners without titles—gained influence, particularly in local governance. Below them were the yeomanry, prosperous farmers, followed by labourers and peasants, who often struggled with economic hardship. Urbanization increased, particularly in London, fostering the growth of a merchant and artisan class.

Religious Upheaval and the Reformation

Religious instability defined much of the Tudor era, as successive monarchs imposed their beliefs upon the nation. Henry VIII’s break from Rome established royal supremacy over the Church, though many Catholic doctrines remained during his reign. His son, Edward VI, a staunch Protestant, implemented further reforms, moving England toward a more radical Protestant identity in his short six-year reign.

However, his premature death led to the reign of his Catholic sister, Mary I, who sought to restore England to papal authority. Her persecution of Protestants earned her the moniker “Bloody Mary,” as hundreds were executed for heresy. (Does she look like a bundle of laughs? Uh…no)

It was three official changes in religion in a short period, exacerbating uncertainty for everyone, with often dire consequences. The five sovereigns had very different religious views and imposed them forcibly. While the definition of a heretic changed with each ruler, they were all hunted down, and many were put to gruesome deaths.

Plaque near Salisbury Cathedral

England experienced a more moderate and pragmatic religious accommodation with Elizabeth I’s accession. Though she firmly established Protestantism, she sought to avoid the violent extremism of her predecessors, famously stating that she had “no desire to make windows into men’s souls.” Her reign provided relative religious stability and allowed England to flourish culturally and politically.

Cultural and Intellectual Advancements

The Tudor period witnessed remarkable advancements in literature, science, and exploration. The introduction of the printing press facilitated greater literacy and the dissemination of ideas, contributing to the spread of Renaissance thought.

England became increasingly engaged in global exploration, with figures such as Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh expanding the nation’s reach and influence overseas while defending Britain from invasion.

Science also advanced and was influenced by Renaissance humanism. Though medicine and natural philosophy were still rudimentary by modern standards, there was a growing interest in empirical observation and inquiry.

Architectural and Artistic Achievements

Tudor architecture reflected both medieval traditions and Renaissance influences. Even today, we have a nostalgic fondness for timber-framed buildings, though we’d likely skip the wattle-and-daub infill!

Manor houses, such as Montacute, built by the wealthy elite, displayed wealth while promoting self-sufficiency—they often incorporated gardens, farms, and workshops.

Larger country houses and palaces showcased increasing grandeur, such as Burghley House, built by Wiliam Cecil, Elizabeth I’s chief advisor, twice Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572), and Lord High Treasurer from 1572.

The Elizabethan Legacy

Elizabeth I’s 45-year reign is often considered a golden age of peace, prosperity, and cultural achievement.

The previous Medieval Period (1066–1485) had been marked by war, famine, and plague, including the devastating Black Death. In contrast, the Elizabethan era saw relative political stability and artistic flourishing, with figures such as William Shakespeare emerging and England’s growing status as a global power.

Despite economic difficulties and religious divisions, the Tudor period laid the foundation for England, which would continue to rise in power in the coming centuries. It was an era of transition, bridging the medieval world with the dawn of the Stuart Era (1603-1714) and remains one of the most defining and fascinating periods in British history.