The Stuart era began in 1603 with the death of Queen Elizabeth I, who died childless. Her cousin, James VI of Scotland, became James I of England, uniting the long-warring nations of England and Scotland.

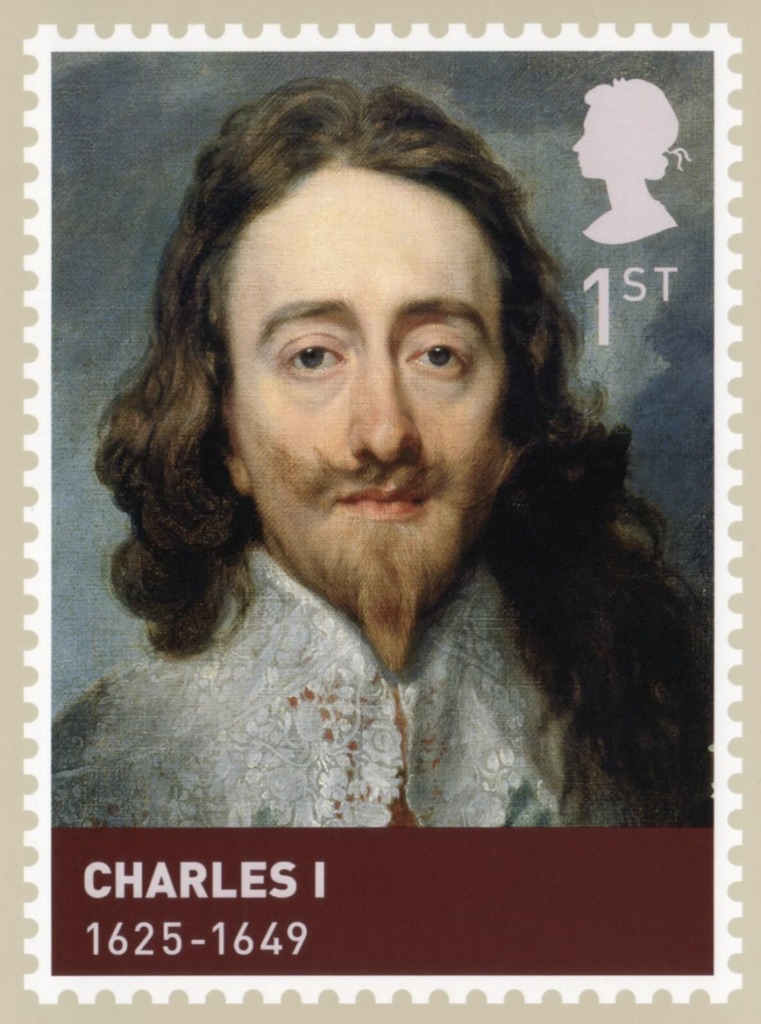

The short Stuart period saw more than its fair share of political and religious strife. In the mid-seventeenth century, a bloody civil war erupted between the Crown (Cavaliers) and Parliament (Roundheads). Authors Sellar and Yeatman describe the factions in their satirical book, 1066 And All That: A Memorable History of England as the Cavaliers: Wrong but Wromantic and the Roundheads: Right but Repulsive.

The Parliamentarians prevailed. King Charles I was executed outside the Banqueting House in London in 1649, to the groans to the groans of the watching crowd.

A decade-long Interregnum followed, largely under Oliver Cromwell’s control. A raft of pamphlets spread revolutionary ideas far and wide. A radical Puritan himself, Cromwell was more tolerant of other religions than of frivolity. His military command advanced national stability, but it was a joyless regime whose ultimate collapse led to the Restoration of the monarchy. Charles II came back from exile to assume the throne, ending England’s brief flirtation with a republic.

Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, reveals that Charles II’s reign was marked by a scandalous court, the resurgence of theatre, and the blossoming of art and architecture. Sir Christopher Wren influenced more than the rebuilding of London after the great fire of 1666, including St Paul’s Cathedral. As Professor of Astronomy at Gresham College, one of Wren’s lectures prompted twelve men of science to form a “College for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematical, Experimental Learning” at Gresham College, London.

This group was later known as The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, or what we would now call science. Wren considered that it should act to transform knowledge, profit, health, and the conveniences of life. The Royal Society still exists to this day as a Fellowship of many of the world’s most eminent scientists and is the oldest scientific academy in continuous existence.

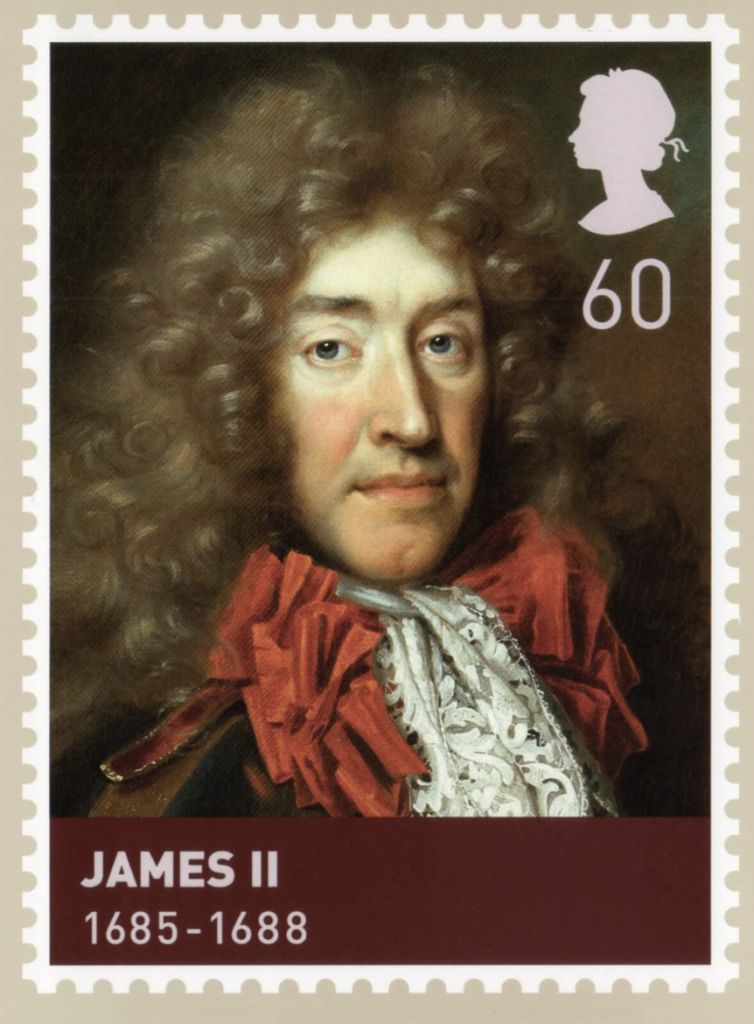

Upon Charles II’s death, his brother, James II, acceded to the throne. James’ conversion to Catholicism in 1669 cast a deep shadow of suspicion regarding his religious loyalties. While his heavy-handed efforts to promote the Roman Catholic cause fomented conflict with Parliament, the birth of a son in June 1688 really set the cat among the pigeons. Fears of a Roman Catholic dynasty seeped among his subjects.

In no time flat, James II was deposed. The ‘Glorious’ Revolution saw him replaced by his Protestant daughter, Mary II, and her Dutch husband, William III. During the joint rule of William III (1689–1702) and Mary II (1689–94), England enjoyed a largely peaceful period.

The Act of Settlement was passed in 1701 to ensure that the throne would henceforth go solely to Protestant hands. Mary’s sister, Anne, succeeded in 1702 and ruled until 1714.

During Anne’s reign, the Duke of Marlborough won famous victories against Louis XIV of France and was rewarded with Blenheim Palace, the “gift of a grateful nation”.

The most significant political event of Anne’s reign was the Act of Union with Scotland (1707), which created a unified Great Britain.

But the succession was up in the air again. Sadly, none of Anne’s eighteen pregnancies resulted in a child who lived to maturity, and the next in line, according to the provisions of the Act of Union, was George Elector of Hanover. For the next half-century, James II, his son James Francis Edward Stuart, and his grandson Charles Edward Stuart claimed to be the true Stuart kings, causing no end of grief, and ending disastrously for Scotland.

The Stuart Dynasty ended with the death of Queen Anne and the accession of King George I from the German House of Hanover.