The Old Palace at Hatfield was the childhood home for all three of Henry VIII’s children but is most closely associated with Elizabeth I. During happy periods in her childhood, it was where Elizabeth shared her brother Edward’s education. Later, it served as a refuge during the tumultuous reigns of her siblings, King Edward VI and Queen Mary, when Elizabeth was often in mortal danger.

Henry VIII spent several weeks at Hatfield in 1522 with his first wife, Katharine of Aragon, to avoid an outbreak of the plague in nearby London. He returned in 1528 to escape a severe epidemic of sweating sickness. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Henry took possession of Hatfield Palace.

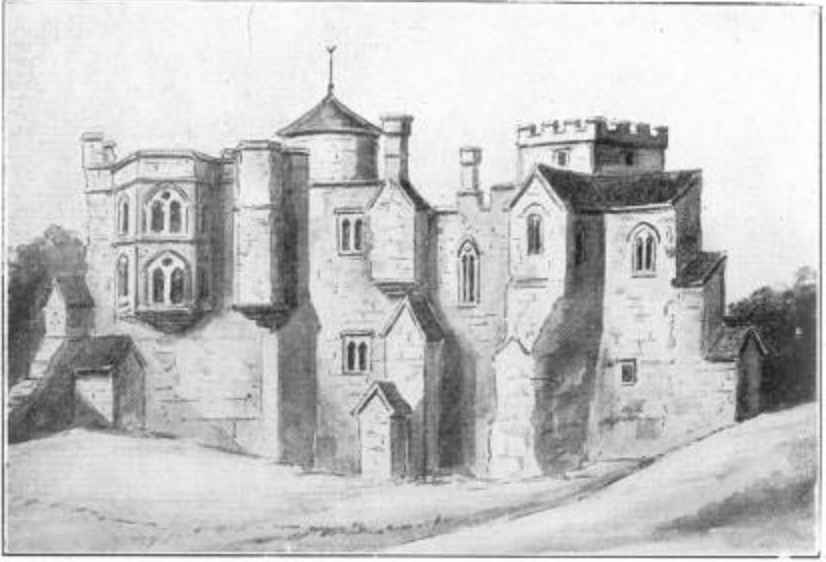

Initially, the diocese of Ely owned the manor at Hatfield, an ideal stopping-off point for travel between London and Cambridgeshire. John Morton, then Bishop of Ely, built the new manor house next to St. Ethelreda’s church, close to an earlier structure.

Elizabeth first came to Hatfield in December 1533 as a three-month-old baby in the care of her mother’s aunt, Anne, Lady Shelton. Anne Boleyn visited her daughter there, safely tucked away from diseases with which London was rife. In the spring of 1534, Elizabeth’s 18-year-old half-sister Mary (daughter of Henry’s first wife, Catherine of Aragon) came to Hatfield to serve as an attendant in the young Elizabeth’s household. As heir apparent, Mary held the rank of Princess, but the annulment of her parent’s marriage reduced her status to a bastard; along with Henry VIII’s self-appointed position as head of the Church of England, Mary steadfastly refused to accept it.

Later, Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, was beheaded on trumped-up charges of adultery, incest and treason. Elizabeth, too, became a bastard. Henry married his third wife, Jane Seymour, in May of 1536. The now ‘Lady Elizabeth’ went to court in 1537 to celebrate the birth of her half-brother Edward, the long-awaited son of Henry VIII. Edward became the sole heir to the throne; neither Mary nor Elizabeth was in the line of succession due to their illegitimacy.

After Edward’s christening, Elizabeth returned to Hatfield, where she immersed herself in her studies. She was an excellent student, tutored by renowned humanist scholars Roger Ascham and John Cheke. She studied Greek and Latin and spoke four other languages: French, Italian, Spanish, and Flemish.

Elizabeth’s state apartments would likely have been on the first floor of the Hatfield Palace in the south range (the bottom of the square below).

After Henry VIII’s sixth and final marriage to Katherine Parr in 1543, the King sought to reconcile with his daughters. Encouraged by his peace-making wife, he reinstated Mary and Elizabeth in the line of succession, though both remained illegitimate.

After Henry VIII died in 1547, thirteen-year-old Elizabeth went to live with her stepmother, Katherine Parr, in Chelsea Manor in London.

King Henry’s will appointed a council of sixteen, including two of King Edward VI’s uncles, Edward and Thomas Seymour, to serve during the nine-year-old King’s minority. With lightning speed, Edward Seymour created himself as Duke of Somerset, Lord Protector of the Realm and Governor of the King’s Person, effectively with the powers of a monarch. It was an incredibly bold move contrary to the stipulation that the entire Council collectively guide the young King. To quell objections, he used Henry’s will’s “unfulfilled gifts” clause to transfer bountiful lands and honours to council members.

The younger brother, Thomas Seymour, beside himself with rage and jealousy, proved more intractable. Intent on a more significant share of power, he demanded to be appointed Governor of the King’s Person. Edward tried to buy him off with a barony and appointed him Lord High Admiral, but it was not enough for Thomas.

Thwarted, Thomas turned his attention to Henry VIII’s widow, Katherine Parr, whom he had courted before her marriage to Henry VIII. She was strongly attracted to him, and with what many saw as unseemly haste, Katherine married him a few months later. The couple, Princess Elizabeth and Lady Jane Grey, placed in Thomas Seymour’s household for advancement, moved to Sudeley Castle, where disaster beckoned.

Now living together, Thomas Seymour began a game of cat and mouse with Elizabeth, appearing in her bedchamber in his nightclothes early in the morning, where he tickled and slapped her on the backside. Elizabeth’s governess, Kat Ashley, was scandalized. She reported the incidents to Katherine, who dismissed the overtures as innocent affection. But by June of 1548, a heavily pregnant Katherine Parr began to see the slap-and-tickle romps in a new light. Elizabeth was removed from Sudeley and placed under the care of Anthony Denny and his wife, Joan Champermowne, Kat Ashley’s sister. Kat and her husband, Thomas Parry, Elizabeth’s cofferer, joined Elizabeth at the Denny’s residence in Cheshunt.

In September, Katherine Parr died of puerperal fever a few days after giving birth to a daughter. She is buried in the chapel at Sudeley.

Nothing daunted, Thomas Seymour resumed his attentions to Elizabeth by letter in a bid to marry her. Elizabeth wrote a diplomatic refusal and hoped the entire matter would be put behind her.

It was not to be. In January 1549, the Council arrested Thomas Seymour on various charges, including embezzling at the Bristol Mint and engaging in a secret plot to marry Princess Elizabeth. Lord Protector Somerset sent Sir Robert Tyrwhitt to extract a confession from the 15-year-old Elizabeth. Tyrwitt interrogated Elizabeth over many days and pressured her to confess. Poised and intelligent, she proved more than equal to the task. Kat Ashely and Thomas Parry were questioned at the Tower of London. It was all a hideous mess, but in the end, nothing was proven. Sir Robert Tyrwhitt gave up in exasperation; Kat and Thomas were released from the Tower and returned to Cheshunt.

The lack of clear evidence for treason didn’t stop the Council; Thomas Seymour was condemned instead by an Act of Attainder and beheaded on March 20, 1549. Elizabeth returned to Hatfield a few weeks later with Kat Ashley and Thomas Parry. On her 17th birthday, Elizabeth was granted the manor of Hatfield outright and remained there for most of her brother’s reign.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, Protector Somerset’s troubles extended beyond his unruly (now deceased) brother Thomas. Historians have commented that the bold efficiency of his power grab in 1547 was not matched by his subsequent rule of the country. He pursued costly and disastrous wars with France and Scotland, virtually bankrupting the crown.

Uprisings broke out around the country, spurred by religious and agrarian grievances. Imposing English church services in a country that had not yet moved on from its Catholic beliefs was unpopular. Let’s not forget that Henry VIII had been a moderate Protestant, at best.

Landlords encroaching on common grazing ground was the basis of the rural protests. The upset was exacerbated by the protestors’ belief that they had the Protector’s support and were acting in accordance with the law. They saw the landlords as the lawbreakers. Somerset was partly to blame for this. He was prone to making liberal, often contradictory pronouncements. One of the commissioners he sent to investigate the uprisings was M.P. John Hales, an evangelical who spouted socially liberal rhetoric that idealized a godly commonwealth.

Somerset dealt with the first rebellion with a relatively light hand, pardoning the protestors who had torn down hedges enclosing common land. But further demands ensued, culminating in the Kett rebellion in Norfolk. The leader, Robert Kett, established a governing council of representatives from the villages that had joined the revolt. Taking over Norwich was a step too far. The rebellion was put down decisively by John Dudley, the Earl of Warwick. Kett and many of the rebels were executed.

Taken together, the Council took the position that Somerset was responsible for a failure in government; a coup d’état ensued. By October 1549, Somerset saw which way the wind was blowing. He called for military assistance and removed himself and King Edward VI to Windsor Castle “for safety”.

A few days later, the Council met and came down hard against Somerset. They summarized their findings that he had mismanaged the government, stating that the Protector’s power was not stipulated in Henry VIII’s will but provided by the Council. By mid-October, Somerset was arrested and taken to the Tower of London.

John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, emerged as the leader of the Council and, in effect, as Somerset’s successor. Initially gracious in his triumph, Warwick released Somerset from the Tower and restored him to the Council. But Somerset’s respite was short-lived.

By July, John Dudley, the Earl of Warwick, had raised himself to the Duke of Northumberland. Exaggerated treason charges were made against Somerset, and by October 1551, he was back in the Tower. He was accused of scheming to overthrow Northumberland’s authority (for which there was evidence) and executed in January 1552.

Perhaps learning from Somerset’s error of autocracy, Northumberland initially took a conciliatory approach to governing, encouraging the now fourteen-year-old King to involve himself in matters of state.

The treasury was nearly bankrupt. Northumberland ended the expensive wars with France and Scotland. He then turned his attention to promoting economic recovery, including halting the debasement of the currency, thereby fighting inflation. To quell further uprisings, he instituted local police, appointing local lord-lieutenants closely tied to central authority. William Cecil, whom we will hear more about later, became Secretary of State and, in effect, Northumberland’s right-hand man.

In early 1553, the King fell ill with a fever and cough, which waxed and waned. A frisson of alarm rippled across the court.

Northumberland moved to consolidate his position through the time-honoured practice of arranging advantageous marriages for his children. One has to admire his thriftiness. In May 1553, he hosted a triple wedding at Durham House, his London residence on The Strand.

Son Guildford Dudley married Lady Jane Grey (daughter of Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk). Northumberland’s youngest surviving daughter, Katherine Dudley, married Henry Hastings (heir of Francis Hastings, the Earl of Huntingdon). The third couple was Jane Grey’s sister Katherine, who married Henry Herbert (heir of William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke). An illustrious group. If only their parents had exercised more imagination in naming their children rather than the dizzying array of Williams and Katherines. Good grief. In an ironic twist of fate, only the last of the three couples kept their heads and marriage. But that’s a story for another day.

Nearly at his last breath, young King Edward’s main concern was ensuring the throne passed to a male Protestant. But devoutly Catholic Mary was next in line. Inspired by his father’s will, Edward wrote a first draft of a ‘Devise for the Succession’, disinheriting his half-sisters Mary and Elizabeth in favour of the male heirs of his cousin, Lady Frances Grey, or her children, Jane, Katherine and Mary.

By June 1553, it became clear that the King was fatally ill. None of the Greys had yet produced a male heir (given that two of them had only been married for a month, this is unsurprising). Edward changed his devise in favour of Lady Jane Grey, who just happened to be Northumberland’s daughter-in-law.

Taking no chances with its legitimacy, the devise was signed by more than 100 notable persons, including the entire Council, many peers, bishops, judges, and London aldermen. To what degree this was scheming on Northumberland’s part is debatable. Many historians see it as plotting to hold on to power; others view the plan as genuinely Edward’s, enforced by Northumberland after the King’s death,

Shortly before Edward’s death, Mary was urged to visit her dying brother in London. Fearful that the summons was a prelude to her capture to aid Jane’s accession to the throne, she decamped to East Anglia, where she owned extensive estates.

Northumberland summoned Elizabeth to London, but she feigned illness, declaring she was too sick to travel. With the political insight that was to mark her long career, she realized that a battle for the throne was soon to ensue, and she would be wise to stay well out of it.

King Edward VI died, likely of tuberculosis, on July 6, 1553. Northumberland set off for Norfolk to capture the person of Mary, who was now ensconced in Framlingham Castle with a military force.

On July 10, 1553, Northumberland and his supporters proclaimed Lady Jane Grey Queen; at the same time, Mary’s letter proclaiming herself Queen was delivered to the Council in London. Two days later, Northumberland’s support crumbled, the Council switched sides, Jane was deposed, and Mary was declared Queen on July 19.

On July 25, 1553, Northumberland and four of his sons, John, Ambrose, Henry, and Robert, were taken to the Tower of London. Nine-day-queen Jane was imprisoned in the Tower’s Gentleman Gaoler’s apartments and her husband in the Beauchamp Tower. They had already been at the Tower of London, where they had come to await her Coronation. What a profound change of circumstances, if not location!

On August 3, 1553, Mary rode into London, buoyed by popular support, accompanied by her sister Elizabeth and a procession of over 800 nobles and gentlemen. Attending Mary’s Coronation on October 1, Elizabeth assumed the role of dutiful sister and loyal subject to Mary, a devout Catholic who was doggedly determined to return England to the true Catholic faith.

The situation was tense. Elizabeth was now heir to the throne. Though she had no option but to conform outwardly to the Catholic faith, she knew she could not afford to distance herself from her future subjects and Protestant supporters. She was in danger of being implicated in plots to overthrow her Catholic half-sister. Elizabeth knew that Mary distrusted her and begged leave to return to Hatfield, away from the political machinations of court.

Northumberland was tried by judges and a jury largely comprising his former colleagues. He was convicted of treason and begged the Queen’s mercy for his sons. He was executed on August 22, 1553.

His sons, including Robert Dudley, future favourite of Queen Elizabeth I, Earl of Leicester, remained in prison awaiting trial. More to come on Robert Dudley.

By the autumn of 1553, a Protestant rebellion was simmering, ignited by Queen Mary’s intention to marry Catholic Prince Philip of Spain, son of Charles V, Emperor of the almighty Hapsburg Empire. As far as Protestant England was concerned, she could not have made a worse choice. Tales of the vicious Spanish Inquisition were rife.

Led by Sir Thomas Wyatt, the rebellion’s main objective was to supplant Queen Mary with Elizabeth. But Mary’s spies intercepted letters between the conspirators, including one from Sir Thomas Wyatt to Elizabeth informing her of the plot. Within 24 hours, Queen Mary issued a proclamation offering pardon to rebels who desisted and declared Wyatt a traitor.

In early February 1554, Wyatt and his rebel army entered London to a lukewarm reception. Londoners mainly supported Queen Mary as the daughter of King Henry VIII and the lawful Queen. The rebels lost heart and deserted in droves. Wyatt was captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London with the other nobles caught up in the rebellion. Though tortured, Wyatt refused to implicate Lady Elizabeth. He was convicted of high treason and sentenced to a traitor’s death: hanging, drawing, and quartering.

Following their arrests in July 1553, Lady Jane Grey and her husband, Guildford Dudley, were still languishing in the Tower. But the Wyatt rebellion ended their clemency. On February 12, 1554, they were both executed.

Once again, Elizabeth was summoned for questioning. Once again, she pleaded illness; Mary wasn’t having it. She distrusted Elizabeth and was impatient with her excuses. Mary sent two of her personal physicians to determine Elizabeth’s fitness for travel. They reported that though she was clearly unwell, her illness was not a bar to travelling the twenty miles from Hatfield to London. Three members of the Privy Council escorted Elizabeth along with some members of her household. Hastings, Howard and Cornwallis were all sympathetic to Elizabeth. Sick with fright, she made the journey in a litter, progressing in easy stages.

Her arrival at the Palace at Whitehall was inauspicious. Mary refused to see her. Elizabeth was separated from her attendants and turned over to Stephen Gardiner for questioning. Gardiner, Lord Chancellor and Mary’s chief advisor, had been a prominent bishop in Henry VIII but had languished in the Tower of London during Edward VI’s six-year reign. Having regained his powerful position, he was disinclined to sympathize with Protestants.

Elizabeth’s previous experience with interrogation stood her in good stead. She handled herself well, repeatedly denying any involvement with the Wyatt Rebellion. Her frequent requests to meet with Mary were refused. She finally gained permission to write to her sister to protest her innocence and declare her loyalty, but it was useless. She was taken from Whitehall to the Tower of London by boat and told to enter through what had recently been named Traitors Gate. Travelling in a steady downpour, the boat passed under London Bridge, where heads of the recently executed were mounted on pikes, a sober reminder of what might lie ahead.

During her imprisonment, Elizabeth was lodged in the Queen’s Lodgings, modest but comfortable quarters on the first floor with a fireplace and three small windows. Kat Ashley and a few of her servants were permitted to stay with her.

She was terrified, constantly reminded of the fate of her mother, Anne Boleyn, who had stayed in those same rooms awaiting her execution. She was haunted by the scaffolding used for Lady Jane Grey’s execution, still visible from her window. It was some comfort to think of her popularity with the Protestant people of England. Daughter of King Henry VIII, she was heir presumptive to the throne. Mary could not afford to be cavalier.

In the photo below, The Queen’s Lodgings are the half-timbered buildings on the left; the brown brick buildings to the right are Gentleman Gaoler’s apartments, where Lady Jane Grey was kept.

The interrogations continued for two months but proved fruitless. With insufficient evidence to put her on trial, Elizabeth was released from the Tower on May 19, 1554, and placed under the “care” of Sir Henry Bedingfield with his company of one hundred men, who accompanied her to Royal Manor at Woodstock in Oxfordshire, an English Royal residence since Saxon times. Surrounded by miles of forest, it was prime hunting land.

The journey took four days, with overnight stops at Richmond Palace, Windsor, West Wycombe and Rycote. Elizabeth was greeted enthusiastically along the route. In the spirit of a Royal walkabout today, common people gathered to express their joy at seeing her, presenting small gifts of sweets and bouquets. Bedington’s men were dressed in a blue livery, lending the entourage the appearance of a Royal procession. Mary’s popularity was waning, and Elizabeth was clearly popular. It must have been very heartening to her after her confined and fearful days in the Tower of London.

Woodstock Palace was dismantled in the 18th century to make room for Blenheim Palace.

The party arrived at Woodstock on May 23. Elizabeth’s status was unclear. Not technically a prisoner, neither was she free to leave. Queen Mary had stipulated that Elizabeth be closely watched but treated as an honoured “guest”. Elizabeth could read, receive visitors approved by Sir Henry Bedingfield and send letters, but all was tightly controlled. She was permitted to take exercise in the grounds under the close supervision of Sir Henry’s guard. One benefit of her virtual imprisonment was that she was well protected from potential assassins.

Much of the Manor House was in disrepair. Elizabeth lived in the Gatehouse at Woodstock with some of her personal servants, though Kat Ashley was not one of them. Kat’s husband, Thomas Parry, Elizabeth’s cofferer, had to lodge in the nearby town of Woodstock as accommodation was limited.

A virtual prisoner, Elizabeth’s spirits and health declined. Mary refused to communicate with her. Eventually, Elizabeth was permitted to write to her sister and the Privy Council, and she did, emphasizing her position as a Royal Princess of England. However, her efforts were greeted with silence.

In July of that year, Queen Mary married Philip, Prince of Spain, at Winchester Cathedral in a lavish event attended by the great and good of England and Spain. Princess Elizabeth was not invited.

Oddly enough, Mary’s husband, Philip, proved to be an unlikely ally of Elizabeth. Spain was at war with France, and Philip needed to finance his troops in Spain—assistance that Mary provided. Mary Queen of Scots was Catholic and allied to France. Of the two possible heirs to the English throne, Elizabeth was the better bet. With an eye to the main chance, Philip gradually brokered a reconciliation between his wife and her sister.

Elizabeth was finally released from house arrest in April 1555. She was taken under heavy guard to Hampton Court, where Queen Mary and Philip were currently residing. Mary continued frosty toward her sister, but Philip wore her down.

In October 1555, Elizabeth finally returned to her beloved Hatfield Palace, where she began corresponding with William Cecil, whom the Duke of Northumberland had employed to administer her properties. He was to become a lifelong friend and her most trusted advisor.

Henceforth, Elizabeth attended court in London only occasionally; her life took on a certain calm rhythm with walks and hunting in the park at Hatfield.

Queen Mary continued her campaign of rooting out and persecuting those who would not conform to Catholicism. Known as ‘Bloody Mary”, she burned some 300 people at the stake, and another 100 died in prison as ‘heretics’, earning her the name of ‘Bloody Mary’.

Mary’s health began to fail. After two false pregnancies, her husband Philip deserted her and returned to Spain. On November 17 1558, Mary finally succumbed to what was likely cancer.

Elizabeth was sitting under an oak tree at Hatfield when Nicholas Throckmorton brought her Mary’s coronation ring, irrefutable proof that Mary had died and that Elizabeth was now Queen of England. Elizabeth sank to her knees, declaring 0 Domine factum est illud et est mirabile in oculis nostris. “It is the Lord’s doing, and it is marvellous in our eyes.”

Several days later, twenty-five-year-old Elizabeth departed for London to be crowned, accompanied by her supporters. Hatfield had been her refuge through happy times and times of great strife. She had been most severely tested, but those experiences, her superb education and profound intelligence prepared her for what lay ahead. She returned to the Old Palace of Hatfield many times in the coming 45 years of her reign, always holding it in great affection.

Only one side of the original quadrangle remains of the Old Palace at Hatfield. The other three sides were dismantled, and the bricks thriftily reused to build Robert Cecil’s nearby prodigy house, Hatfield House, which he began building in 1608.

This aerial view gives us a good sense of how the two properties align: the Old Palace in the background and the newer Hatfield House (which will get its own well-deserved write-up) front and centre.

Robert Cecil was the younger son of William Cecil, Queen Elizabeth I’s chief adviser during most of her reign.

William Cecil, who was made 1st Baron Burghley, served twice as Secretary of State and then as Lord High Treasurer in 1572 and was the Queen’s closest advisor. He is the gentleman to the right of the Queen in the picture below.

It shows Elizabeth receiving the news of her accession to the throne.

William Cecil had two sons, both prominent in politics, though the younger son, Robert, was the more brilliant of the two. From William Cecil’s marriage to his second wife, Mildred Cooke, he was appointed Secretary of State in 1590 and the Queen’s Chief Minister after William Cecil died in 1598. Robert continued to work under Elizabeth’s successor, King James I, becoming 1st Earl of Salisbury in 1605.

James I inherited Hatfield along with several other crown properties. In a somewhat convoluted turn of events, Hatfield came into Robert Cecil’s hands by exchanging properties with King James I. Robert Cecil’s home, Theobald (pronounced “Tibbles”), was magnificent. Nothing remains of it now, but this video gives you a sense of what the grand, moated Palace looked like. King James I, comparing Hatfield Palace to Theobolds, “requested” that Robert Cecil exchange with him in 1607.

When William Cecil died, his elder son, Thomas, inherited the sumptuous Burghley House in Stamford, Lincolnshire, along with his seat in the House of Lords as 2nd Baron Burghley.

Though his career is considered less illustrious than that of his father and half-brother, he was an able soldier and fine politician. He was created Earl of Exeter on May 4, 1605, the same day Robert Cecil was created 1st Earl of Salisbury.

The sole remaining side of Hatfield Palace, with its Great Hall, stood alone and neglected for centuries, even sinking to the lowly role of stable at one point, while the shiny new Hatfield House stood smugly by.

The Salisbury family continued to prosper, and in 1789, the 7th Earl, James Cecil, was elevated to the rank of Marquess. In 1915, the 4th Marquess of Salisbury (1861-1947) finally restored what remained of the Old Palace to its former glory.

The Old Palace is rarely open, but we were lucky that the day before our visit, a wedding took place in the Banqueting Hall, and access to the Palace was open!

No one seemed to be bothering, so we made our way through the Palace to the knot gardens in the back, restored in 1984 by the 6th Marchioness.

A golden angel tops the finial in the midst of a fountain.

The wedding detritus had been cleared away, and the new setup seemed to anticipate a speaker with about 100 chairs facing forward.

We enjoyed touring the extensive gardens between the two houses before venturing into Hatfield House for a tour.

I’ll write up Hatfield House, Burghley House, and Hampton Court soon. These magnificent houses have so much rich history! I don’t know what I enjoy more—the touring, the research, and getting to know the characters.

I hope you enjoyed our visit to The Old Palace, Hatfield House.

Queen Mary

Queen Mary

Source

Source

Helen, I think I need paper dolls to keep up ! What an interesting history lesson. There is never a mention of toilet facilities or installing bathrooms later. Where did they go ?

Happy Easter

Happy Easter, Myrna! Yes, the number of players is astonishing, and since they all seem to have the same first names, it gets very confusing. Then there are the titles, which differ from the person’s surname. But it’s fun!

Toilet facilities for most people were “privies” or outhouses. In the castles and stately homes, there were garderobes (effectively latrine shafts that went down the outside of the building into a moat, river or side of a cliff).

Thanks so much for stopping by.

Best,

Helen

Dear Helen, Many thanks for this comprehensive write-up of what is probably the most interesting period of English history. The Tudors were fascinating, brilliant, complex, perverse, Machiavellian. Poor Dudley–what do you make of his right hand? The English sweat has never been explained, but hantavirus is the likely culprit. I’ve lived near some of these places but have only poked around Blenheim and Hampton Court, more years ago than I would like to think, back in the days when you could poke around. Are you going to the members’ meeting? Happy Easter!

Hi Beatrice,

Happy Easter to you, also! I hope you had a relaxing day.

The Tudors were, in the words of Bertie Wooster, a “rum lot”. What a cast of characters!

Poor Dudley pretty much sums it up. He got titles and properties, but never the prize. I enjoyed listening to Alison Weir’s The Lady Elizabeth and the Marriage Game (fictionalized, but she is also a serious historian, so the books didn’t depart tooooo much from reality. Just a lot of “colour”, mostly about how much Elizabeth vacillated.)

The sweating sickness is intriguing, especially how it just disappeared; the rodents certainly didn’t.

I’ve got to post the pictures for sumptuous Hatfield House and Burghley House, too. Those Cecils are a fascinating group, as was Francis Walsingham. The spy network was alive and well.

Not doing the members this year, but will be going to the Revival. Are you going to either?

Best,

HK