The first leg of our most recent trip to England began with a 10 pm arrival at the Mayfair Townhouse just off Piccadilly, across from Green Park. Having arisen at 2:30 am to catch a very early flight out of Toronto, we had no trouble falling asleep promptly. Very unusually for us, I set the alarm to get us up at 7 am as we had tickets to tour the Palace of Westminster at 9 am. We normally take our time arising on the first day, but the UK parliament buildings are rarely open to visitors, and I was eager to see them. It’s about a 30-minute walk, so with a bit of groaning (and coffee), we got ourselves up and moving.

The Palace of Westminster is one of London’s iconic sights; weirdly, we’d never visited it. But in these days of in-your-face social activism and deprecation of all things colonial, I’ve been curious about how the balance of power between the divine right of Kings and the utterly powerless-at-the-time serfs evolved since the Norman Conquest in 1066.

The UK’s parliamentary and judicial systems are the basis of the US and Canadian systems in slightly different forms. In the 17th century, America’s founding fathers essentially imported the UK system minus the monarchy. The balancing powers of the House of Representatives, Senate and President are not so very different to the House of Commons, House of Lords and the monarchy in the UK.

Big Ben is instantly recognizable; the lesser known Victoria Tower, at the other end, is nearest Westminster Abbey.

We lined up outside in frigid temperatures, waiting to go through security. The east end of Westminster Abbey is right across the road from the entrance to Westminster Palace.

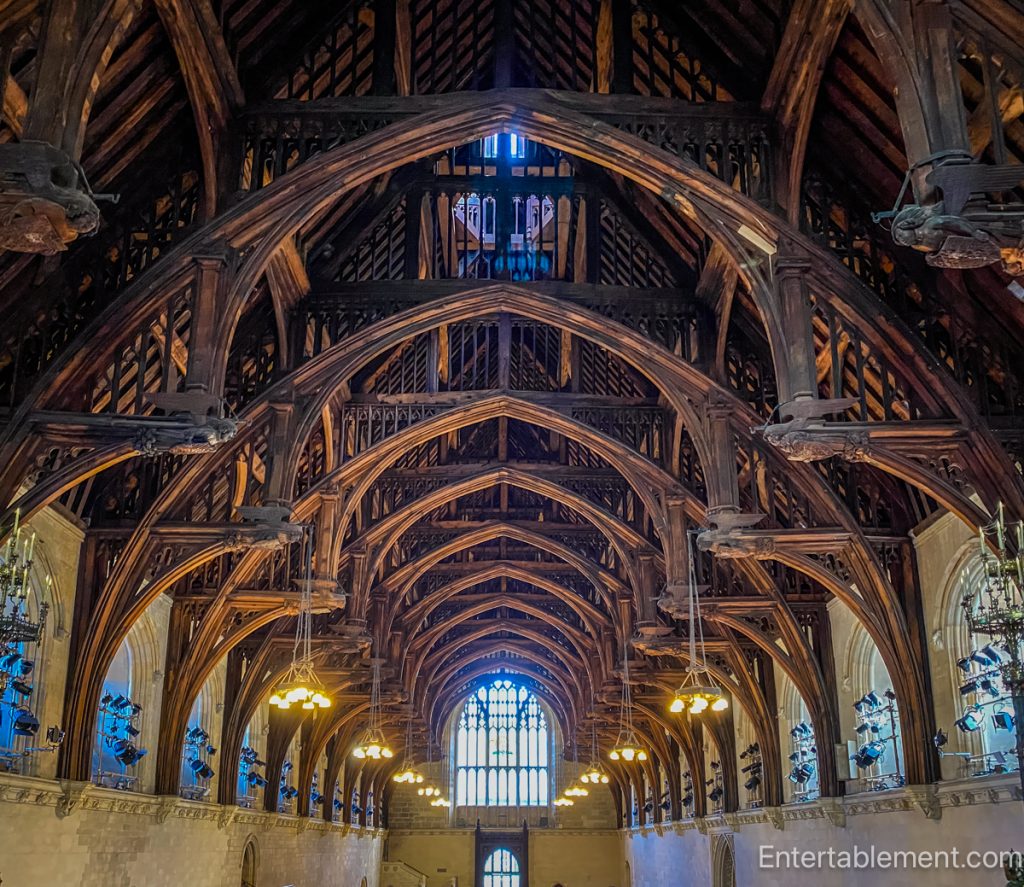

My primary interest in the Palace of Westminster — the Royal family’s residence during the 11th century — was Westminster Hall and its fabulous hammerhead roof.

The first Westminster Hall was built in 1097 by Rufus, son of William the Conqueror. Richard II built the current structure in 1393, his only notable contribution to royal architecture.

The hammer-beam roof is the largest of its kind in Europe. A giant cupola is in the centre to bring light down into the hall below.

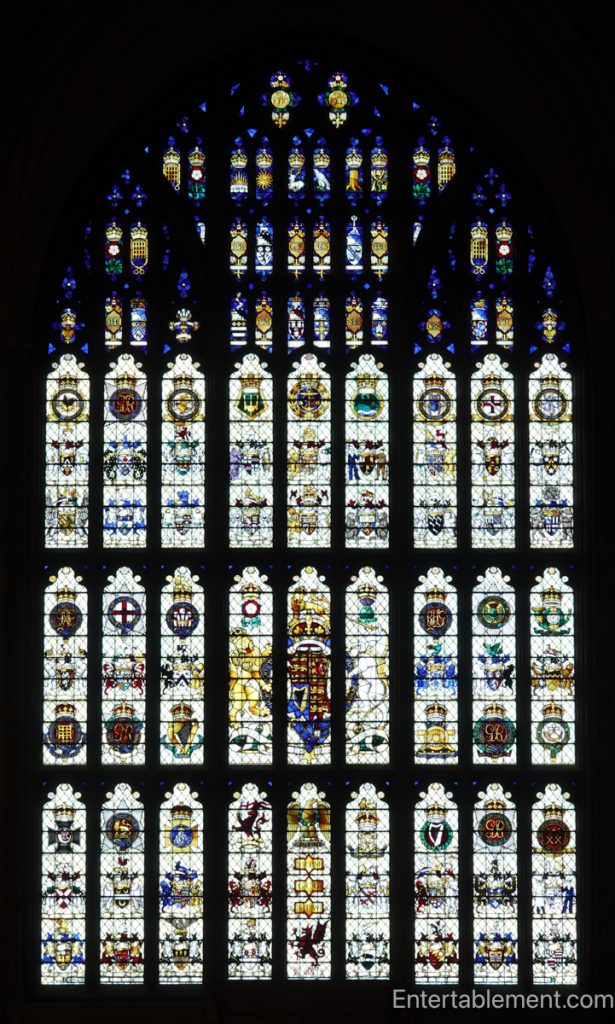

While the stained glass window in the picture above looks small, the scale is deceiving. It’s huge!!

Westminster Hall served as government offices, including the Exchequer (now the Treasury) and the law courts, and served as a grand chamber to entertain notable guests. In later years, it is where members of the Royal Family — most recently, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II — lay in state before their funerals at nearby Westminster Abbey.

It was also the early gathering place for what came to be known by the 13th century as Parliament. Since Anglo-Saxon times, councils had advised the King of bishops and barons, and things could get mighty testy as factions grappled for power and influence. By 1215, matters had become very tense, and in 1215, King John (1166-1216) was forced to accept the limits to the monarch’s authority, enshrined in the Magna Carta. It was the first time a monarch formally acknowledged the legal rights of his subjects, including the right to a trial by jury before being condemned.

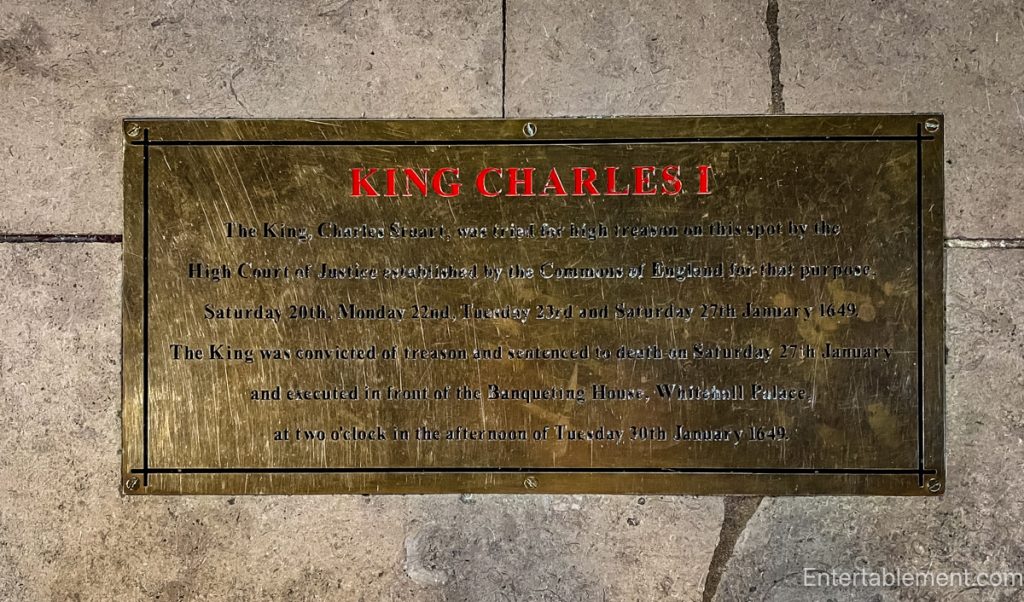

The power struggle continued to evolve over the ensuing centuries and, at times, got very, very messy. Another plaque notes where Charles I sat during his trial for treason.

Charles I was the only monarch ever executed.

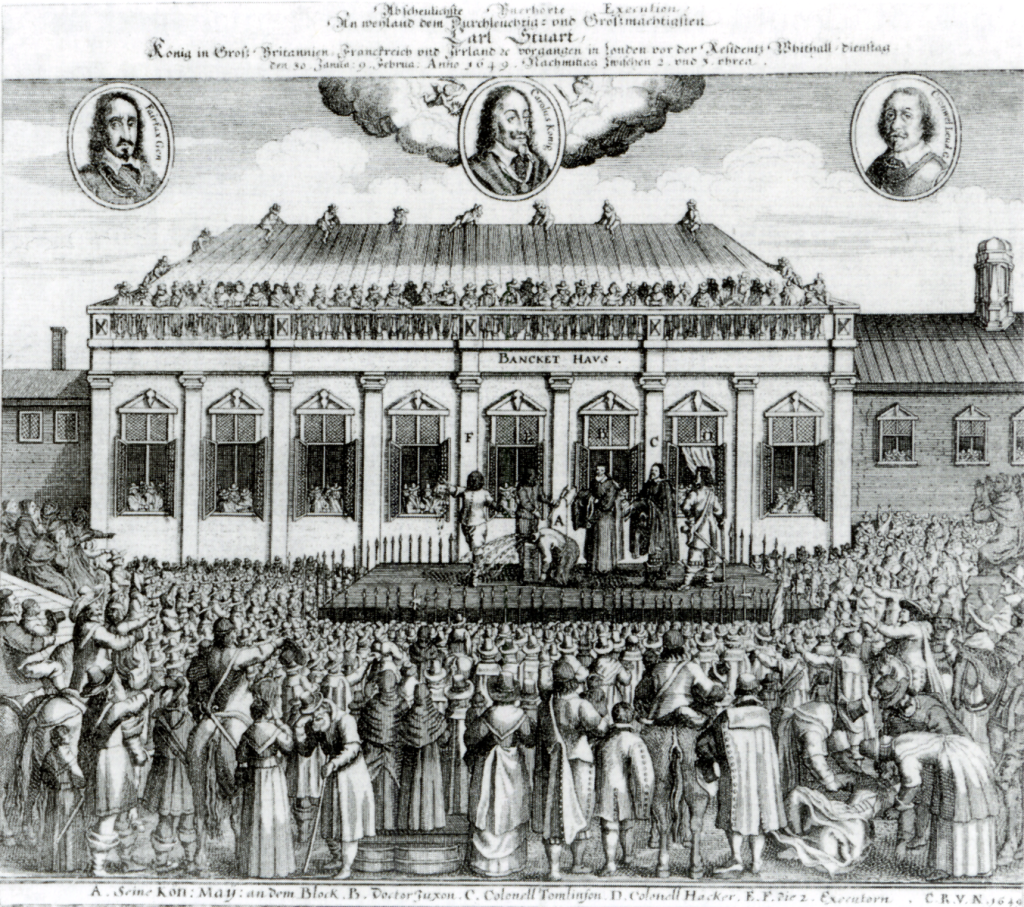

As the plaque mentions, on January 30, 1649, Charles I passed through the Banqueting House, part of Whitehall Palace (enormous at one point, now largely destroyed). This wasn’t one of the rare days it was open, so we could only see the exterior. I’m eager to return as the spectacular ceiling by Rubens is well worth a visit.

After that, England was governed under a Commonwealth ruled by Oliver Cromwell, which lasted only a decade.

The populace found that he was just as greedy and self-interested as the King they had executed, and Cromwell was a lot less fun. Accordingly, when Cromwell died, they invited Charles II back as Monarch (er…sorry about your Dad…no hard feelings?)

St Stephen’s Hall is the only place in the Palace of Westminster where photos are allowed.

A statue of Charles Fox, a famous Whig (Liberal/Democrat) who was a proponent of American Independence, the abolition of slavery, and an advocate of religious tolerance and individual liberty.

Fox was a staunch rival to William Pitt, the Younger, a Tory (Conservative/Republican). Their rivalries, carried on from those of their respective fathers of the same name, were legendary.

Here we have the Earl of Clarendon, chief advisor to Charles I during the First English Civil War and Lord Chancellor to Charles II from 1660 to 1667. Mystery buffs might enjoy the excellent Thomas Chaloner Series by Susanna Gregory. As described on Amazon:

The first adventure in the Thomas Chaloner series. The dour days of Cromwell are over.

Charles II is well established at White Hall Palace, his mistress at hand in rooms over the Holbein bridge, the heads of some of the regicides on public display. London seethes with new energy, freed from the strictures of the Protectorate, but many of its inhabitants have lost their livelihoods. One is Thomas Chaloner, a reluctant spy for the feared Secretary of State, John Thurloe, and now returned from Holland in desperate need of employment. His erstwhile boss, knowing he has many enemies at court, recommends Thomas to Lord Clarendon, but in return demands that Thomas keep him informed of any plot against him. But what Thomas discovers is that Thurloe had sent another ex-employee to White Hall and he is dead, supposedly murdered by footpads near the Thames. Chaloner volunteers to investigate his killing: instead he is dispatched to the Tower to unearth the gold buried by the last Governor. He discovers not treasure, but evidence that greed and self-interest are uppermost in men’s minds whoever is in power, and that his life has no value to either side.

Then, we got to tour the House of Commons and the House of Lords. No photos were allowed, but it was a fascinating look into how the UK government operates and to see the Norman Porch in the Victoria Tower, where the sovereign, now King Charles III, arrives and proceeds to the Robing room where he dons the Imperial State Crown and parliamentary robes before processing to the red upholstered House of Lords. The green upholstered chamber, so often seen in the news, belongs to the House of Commons. As I can’t provide pictures, I only recommend that the tour is well worth it. Here is a link to YouTube virtual tours.

That afternoon, we visited Kensington Palace. This was at least my third visit, but as the separate threads of history begin to knit together in my mind, different aspects of architecture stand out for me. Compared to Windsor Castle, for example, Kensington Palace is a recent inductee into the Royal Palace lineup.

Originally called Nottingham House, it was the country retreat of joint monarchs William III and Mary from 1689. Subsequent Stuart and Georgian monarchs improved on it. Queen Anne added the Orangery, which now serves a lovely afternoon tea.

Queen Caroline, consort to King George I, developed the palace and gardens. William Kent’s painted staircase is glorious.

Queen Victoria was born there and so remained until she went to live in Buckingham Palace in 1837 upon becoming Queen.

An exhibition on Queen Victoria’s childhood is currently on display, and I got a deeper appreciation for her highly restricted childhood. Her education took place almost entirely within the confines of the palace, with virtually no other children to play with. Her daily programme of lessons, known as the ‘Kensington System’, lays out the dos and don’ts.

She was kept away from life at court, as her mother and John Conroy, her advisor and Comptroller, hoped to rule as regents should Victoria accede to the throne before gaining her majority. Happily for Victoria, she had just turned eighteen when her uncle William IV died, and she became Queen. She insisted on attending her first council meeting on her own, beginning as she meant to go on. Pretty gutsy for a young girl who had been so cabin’d, cribb’d and confined. Below is a model of the meeting set out in the Palace. Loved it!

Today, Kensington Palace is the London home of The Prince and Princess of Wales and their children, and it serves as a grace and favour property for more distant working members of the royal family. I really enjoyed the series Victoria by PBS. Jenna Colman was brilliant as young Victoria and loved Rufus Sewel as Lord Melbourne and Lawrence Fox as Lord Palmerston. It’s well worth watching!

Ashridge was originally one of the Royal palaces where Henry VIII’s children (Mary I, Elizabeth I and Edward VI) spent their childhood. Only about 40 miles away from London, it was far enough away to escape disease. Ashridge was originally a wealthy monastery, but after the Dissolution in 1538, Henry VIII took it for one of his houses.

Elizabeth I inherited it upon Henry VIII’s death, and it was there that she was arrested by her charming sister, Mary, on suspicion of treason.

From there, Elizabeth was taken to the Tower of London and interrogated for two months before being finally released. It must have been utterly terrifying. She was housed in the same rooms where her mother, Anne Boleyn, was held before being beheaded. The scaffold erected for the execution of Lady Jane Grey was still in place right outside the window. Not a fun time for Elizabeth. She never returned to Ashridge after that. Can’t imagine why…

All that remains of the monastery is the well. This rendition of the house was built in the early 1800s and is used as a business school and conference centre/wedding venue.

Charles I’s wife, Henrietta Maria, finished the Queen’s House before fleeing into exile upon the death of her husband. It’s the first genuinely classic building in England, a departure from the heavily Gothic style that preceded it. Typical of Classic Architecture, the entrance is on the ground level through a modest single door between the two horseshoe staircases.

Besides being chock full of art, the house is famous for its “tulip” staircase. They’re actually lilies.

Next up, East Anglia and Kent.