The Diocese of Blackburn was carved out of the Diocese of Manchester in 1926, and the parish church of St Mary the Virgin became Blackburn Cathedral.

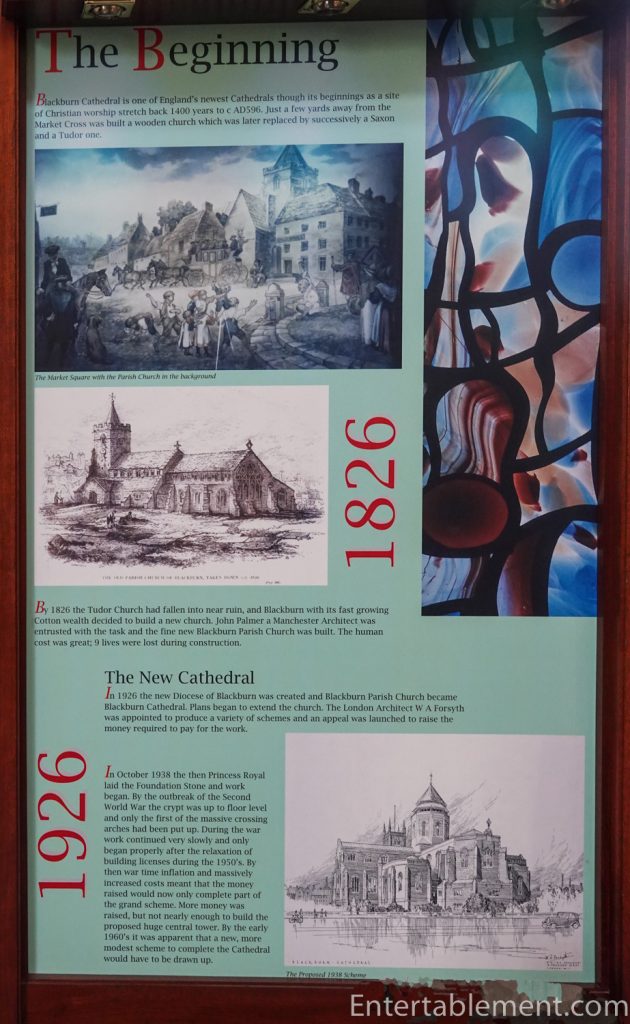

Blackburn asserts evidence of Christian activity since 596. In 1820, when the foundations of the oldest part of the current church were excavated, blocks of stone incised with Norman patterns were uncovered.

In the fourteenth century, St. Mary’s was rebuilt in the Decorated style during the reign of King Edward III, but that church suffered horribly at the hands of Cromwell’s henchmen, and only fragments of glass from the medieval church survive.

By 1818 the old church was in a deplorable state. The powers that be decided on an entirely new building.

John Palmer designed a Gothic Revival church which comprises the nave of the current building.

I hear you thinking—that looks awfully modern for an early 19th-century church. You are correct. It got a 1960s makeover.

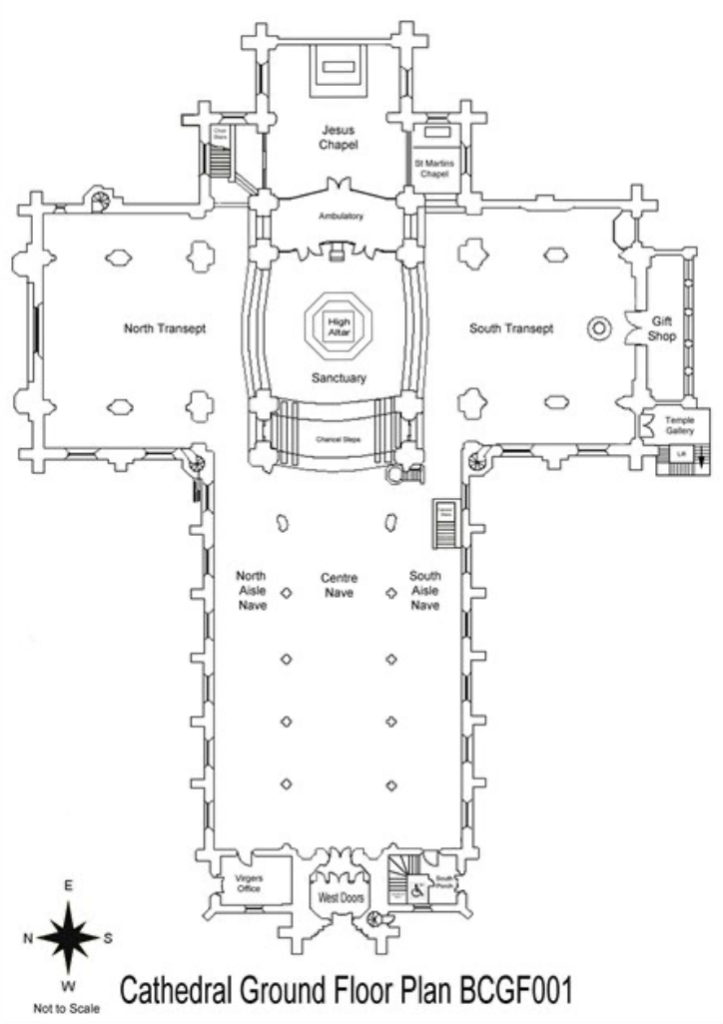

When Blackburn was chosen to form the new diocese in 1926, it was partly because St. Mary’s had a large churchyard that fell away sharply to the east. Extending the church would create space for the Cathedral on both the ground and undercroft levels, with potential meeting rooms under the Cathedral proper.

Architect W A Forsyth’s plans from 1933 included a refectory, library and chapter house—a good old-fashioned Cathedral complex. The old parish church was to form the nave and receive a large central tower, hefty transepts and an extended chancel.

Funds were raised, and in 1938, the Countess of Harewood laid the foundation stone. But the outbreak of World War II drew everything to a screeching halt.

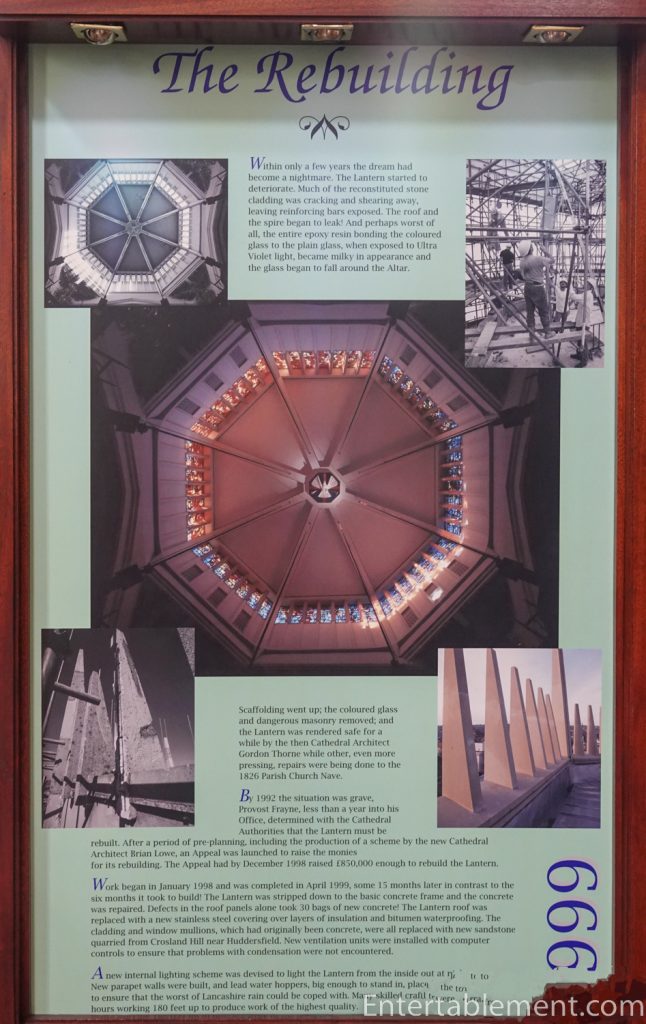

It was 1950 before work could be resumed. The original architect, Forsyth, passed away that same year. Post-war, costs had risen sharply, and materials were in short supply—back to the drawing board. In 1961 Laurence King was appointed as the new architect.

King adapted Forsyth’s design, replacing the proposed central tower with a lantern and placing the sanctuary directly beneath it in the central crossing.

Churches “in the round” were very popular in the 60s—my mother’s famous raised eyebrow was lost in her hairline when our new parish church was built along similar lines. Worse, I thought she would have an apoplexy when confronted with the modern stained glass. Having attended convent boarding under the auspices of Jesuit nuns, my mother had very fixed ideas about ecclesiastical architecture. She had emigrated to Canada by the time Blackburn was built. Thank heaven.

The interior features light—painted walls and pale wood.

The pulpit has an old-fashioned canopy, which was an early method of amplifying sound.

Some stained glass was retained—this window is in the Jesus chapel, at the far east end.

But the majority of the Cathedral features clear windows.

On the plus side, Blackburn is light, airy and welcoming.

On the downside, what is this obsession with spikes and nails?

Good grief!

Blackburn’s website describes it:

“… the striking Corona, both a crown of suffering and a crown of glory… our eyes are taken upwards by the intentionally thick cables to the central boss of the Lantern Tower depicting the Holy Spirit. “

Coventry’s new Cathedral has a similar crown of thorns; theirs forms a partition for a chapel.

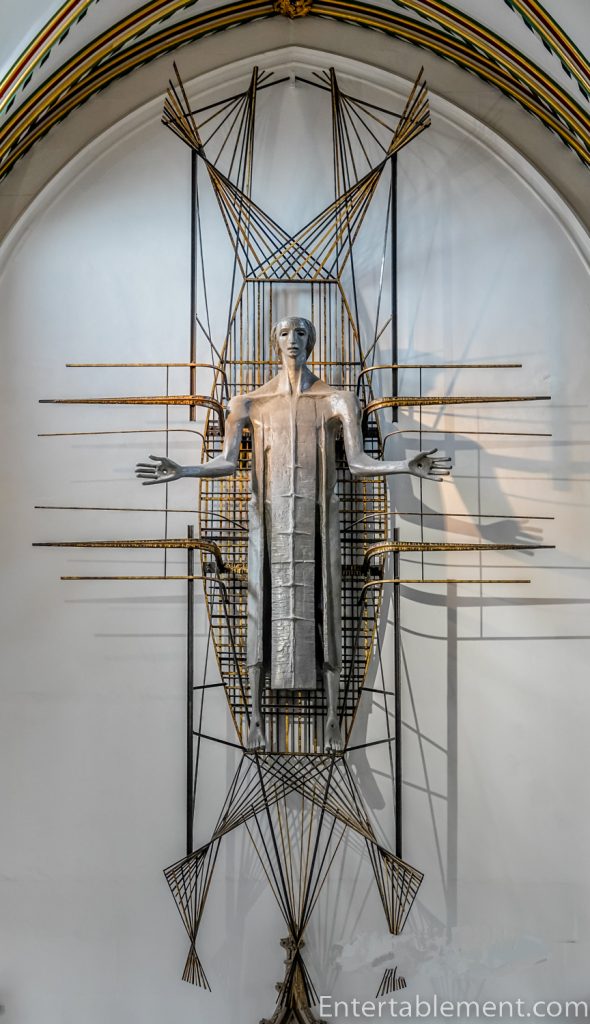

At Blackburn, the Worker Christ at the rear of the nave is also by John Hayward, the artist who designed the Corona—enough said.

Coventry gave us “Our Lord of the Egg”.

Blackburn gives us “Our Lord of the Spike”.

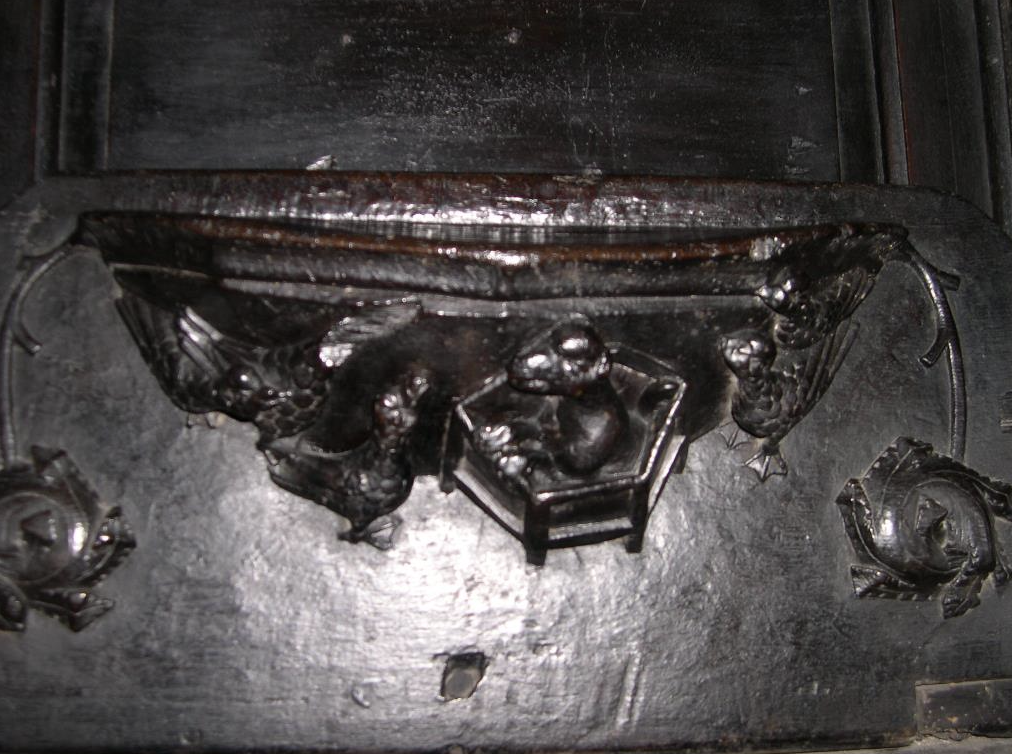

The most surprising feature of such a modern building is the eight misericords, made in the 15th century and now in the North Transept of Blackburn Cathedral.

Where had they been all this time? One possibility is they came from nearby Whalley Abbey, which was dismantled during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. They may also have been part of the 14th-century version of St. Mary’s Parish church that was so badly treated during Cromwell’s time. Have they been stored in a builder’s yard for 300 years? It’s a mystery!

This one is a little hard to see, but it’s a fox in the pulpit preaching to geese, a common satirical theme from the medieval era.

Back in the nave, we can see that the side aisle ceilings are painted in an airy pale blue.

They overlook the Cloister Garth, a peaceful outdoor space.

Let’s go outside and take another look. The lantern was clad in stone in the late 90s, covering the previous concrete exterior, and it blends in well now. But, stepping back, I can’t help but feel that the lantern wouldn’t be quite as incongruous were it not for the space-age spike topped with a tiny cross.

Ely Cathedral has a central lantern, and it looks fits in beautifully.

There are some beautiful details on the older part of the Cathedral.

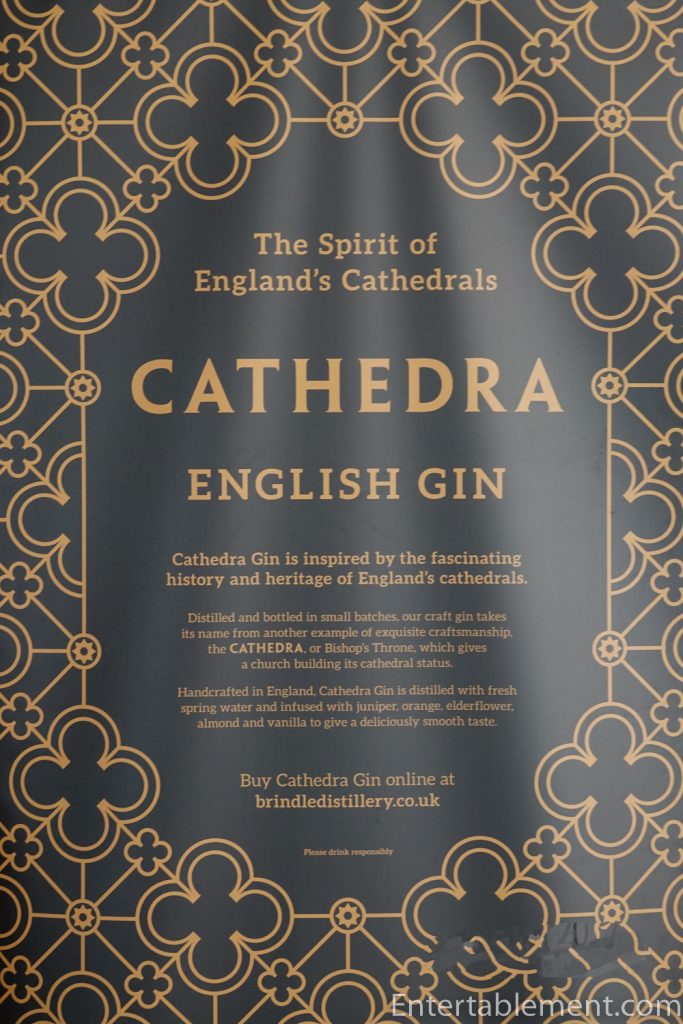

Pausing at the gift shop before finally taking our leave, I was amused to see them selling Cathdra Gin. That’s the spirit!

Cheers!