Bradford is one of three Cathedrals in the Diocese of Leeds, the others being Ripon and Wakefield. The present church, the third on the site, was built in the 15th century and incorporated elements from the previous building.

Standing high on the hillside above the “broad ford” for which it is named, the site has been a place of Christian worship for nearly 1400 years, likely resulting from Bishop Paulinus’ mission of 627 to 633, under the auspices of the court of King Edwin of Northumbria.

Two fragments of carved stone crosses, dating from Anglo-Saxon times, were excavated in the 19th century and can be seen today in the walls of the North Ambulatory.

When the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086, Bradford was part of the parish of Dewsbury; Ilbert de Lacy, who came over with William the Conqueror, was the Norman lord of the manor.

A small stone church was built around 1200. In 1251, a charter was issued for weekly Sunday markets, encouraging both commerce and regular church attendance.

The parish of Bradford, distinct from the parish of Dewsbury, was first mentioned by the Archbishop of York in 1281. The de Lacy family endowed the parish of Bradford and granted it 96 acres of land, used as a burial ground and to hold markets and fairs.

Scottish raiders burnt down most of this stone church in c1327. Rebuilding, delayed by war, famine and plague, commenced in the late 14th century and was completed by 1458. It included the nave arcades and proprietary chapels for the Leventhorpe and Bolling families. The tower was added in 1508 and is primarily attributed to the efforts of Sir Richard Tempest.

The two chapels were dissolved during the Reformation, and the rood screen across the Chancel was destroyed. Luckily, the stairs that led up to it survived. Part of the Leventhorpe Chapel wall, together with the beautiful carved wooden font cover, also survived this period in the building’s history.

The stone font itself is carved with images significant to Bradford, including the sheep.

The cover can be lifted with a rope.

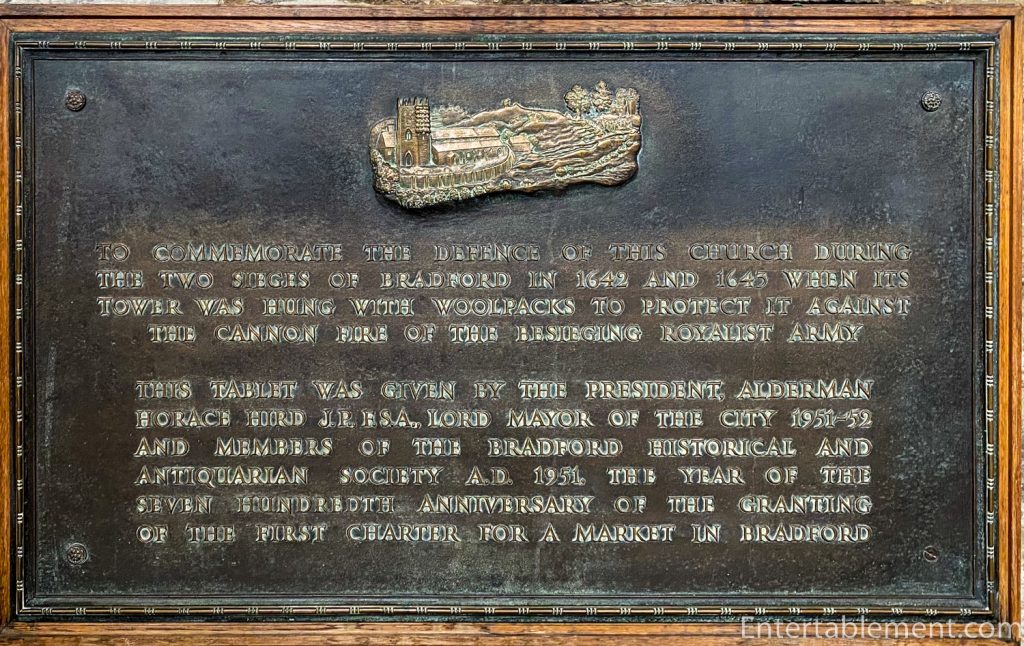

The town was besieged during the Civil War. The church tower was threatened with Royalist cannon fire at the Battle of the Steeple in July 1643.

The townspeople banded together and wrapped the tower with woolsacks for protection, prompting the inclusion of the woolsack on the Cathedral coat of arms.

I think this also accounts for the sheep carvings on the choir stalls.

Not sure of the significance of the lion. The lion lies down with the lamb, perhaps?

While we are here, let’s look at the sanctuary. Interesting that it features the same blue we see at Guilford Cathedral.

The original four bells were first hung circa 1666. Bradford’s long-time, solitary public clock was installed not long after.

An oak roof was installed in 1724, replacing the oft-repaired thatched one.

The 18th century witnessed a surge of religious revival. As the only Anglican church in this area, Bradford Parish Church attracted large congregations, often exceeding 3,000 parishioners. Galleries above the north and south aisles and across the west and east ends of the church were incorporated to shelter the crowds. Walls were whitewashed, and a false ceiling was installed. The aisle roof was raised to accommodate the galleries; a triple-decker pulpit was sited halfway down the church.

A church and chapel building programme in the mid-19th century dispersed the large congregation. The redundant galleries and false ceiling were removed, and a major restoration project began, followed by the addition of transepts in the late 1890s.

Bradford Parish Church became a Cathedral in 1919, carved out of the Diocese of Ripon. Plans for a significant extension to the building were delayed in the aftermath of the First World War. In 1921, the bells, now numbering ten and in poor condition, were recast in memory of the men of the parish and city who gave their lives in the War.

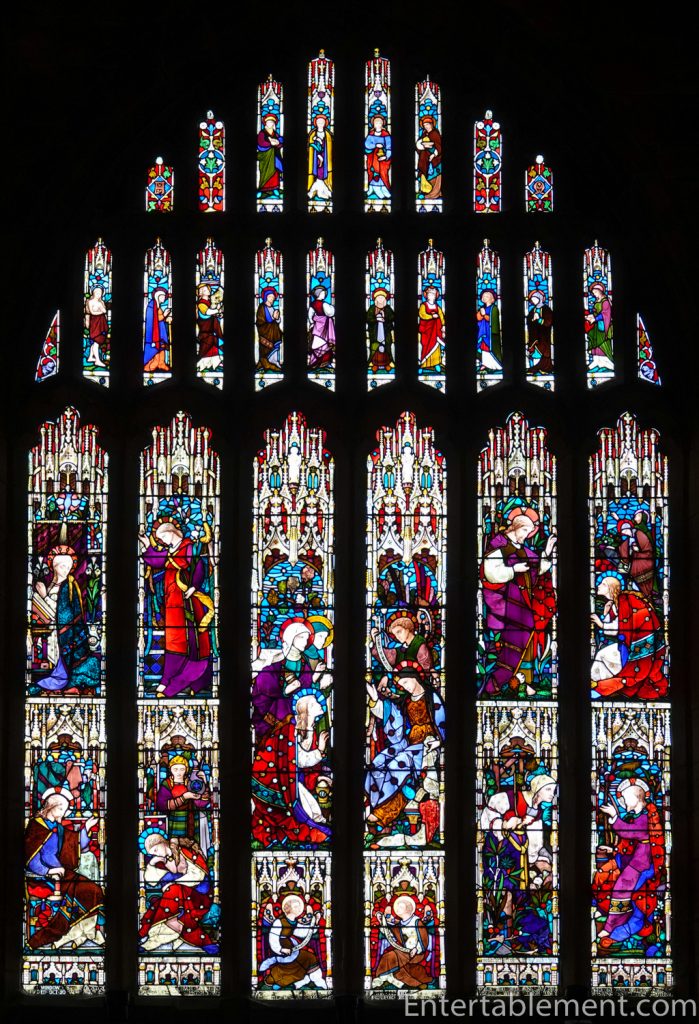

A closer look at the stained glass in the West End featuring women of the Bible.

In the early 1950s, approval for an extension was granted according to a design by Sir Edward Maufe (also the architect of Guildford Cathedral).

Over the next decade, the east end of the Cathedral was rebuilt and extended.

The original William Morris stained glass from the old East Window was reworked in the new Lady Chapel.

The renovation included a new Chancel, Sacristy, St Aidan’s Chapel, a Chapter House, the Chapel of the Holy Spirit, a Library and Muniments Room, and Ambulatories to the north, east and south. It was pretty extensive!

In addition, wings for a Song Room and offices were added at the west end.

In 1987 the Nave and west end were re-ordered to accommodate an increased number of visitors, as well as Cathedral occasions commanding large numbers of attendees. The Victorian pews were replaced by chairs, affording greater flexibility.

Carved and painted angels gaze down from the walls of the Nave.

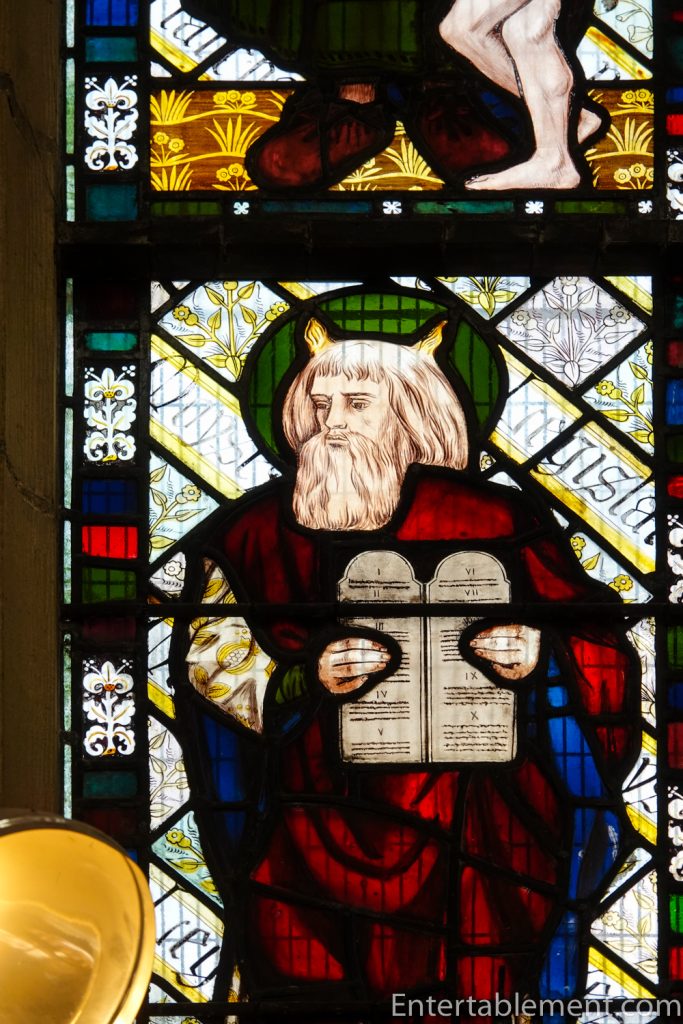

Much Victorian stained glass remains throughout the Cathedral, but it’s light-filled nonetheless.

Following Maufe’s renovation, the northern part of the graveyard was landscaped to form a Close, and houses were built for the Provost (now the Dean) and two Residentiary Canons. In addition, the Parish Room was altered so that it could be entered from the Close. No cat door, though, harrumphs the Cathedral Cat.

Go ahead, try me.

Thought not.

Be on your way now! Bye! Thanks for visiting. Next time, bring treats.