A House Built for Power

Hatfield House is a grand testament to the ambitions of Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, the younger son of William Cecil, Elizabeth I’s trusted advisor.

Built in the early 17th century, it replaced the Old Palace of Hatfield, where Elizabeth spent part of her childhood and famously learned of her ascension to the throne.

Robert Cecil acquired the Old Palace of Hatfield in a land exchange with James I, swapping his family’s beloved estate of Theobalds, which had long been a favourite royal residence under Elizabeth I. Theobalds was a grander estate (later demolished during the Civil War). Its proximity to London made it an ideal retreat for James, and Robert saw the opportunity to consolidate his power base by securing Hatfield.

Recognizing the need for a grander, more modern residence befitting his status, Robert demolished much of the Old Palace and built the magnificent Hatfield House we see today.

Architecture and Grandeur

Hatfield House is one of the finest examples of Jacobean architecture. From the moment you enter the vestibule, you are greeted by a feast of architectural detail and entrancing items collected over the centuries by the Cecil family.

The Marble Hall establishes its stately presence with dark wood panelling, soaring ceilings, and checkerboard marble flooring.

The Coat of Arms of Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 7th Marquess of Salisbury with the motto “SERO SED SERIO” meaning “late but in earnest”.

Aren’t the ceiling panels beautiful?

It remains much as it was when Robert Cecil built it in 1611. The extravagant wood carving is by John Bucke, a premier craftsman of the period.

The embroidered banners hanging from the Gallery feature bees and imperial eagles, symbols of Napoleon. Copied from originals made just before the Battle of Waterloo, they were given to the 2nd Marquess by the Duke of Wellington, a great friend of the family and a frequent visitor to Hatfield.

The famous ‘Rainbow Portrait’ of Elizabeth I, symbolizing her enduring authority, faces the entrance to Marble Hall. The name comes from the motto “Non sine sole iris” (no rainbow without the sun), referring to Elizabeth as a peacemaker after a period of storm.

The Grand Staircase

The extensive carving and collection of weapons speak to the house’s historic role as both a fortress of influence and a luxurious residence.

The intricate ceiling was the work of the (apparently very busy!) 2nd Marquess for Queen Victoria’s visit in 1846.

Its rich gold and russet colours have recently been refreshed. They complement the red silk paper lining the walls and provide a sumptuous backdrop for the tapestries.

I wonder if that poor cherub ever gets tired of holding that instrument aloft. 🙂

I particularly loved the chair on the landing as the staircase turned upward. With all that carving on the back, it doesn’t invite anyone to linger!

King James Drawing Room

The principal drawing room of the house takes its name from a life-sized statue of King James I, presented by the man himself! I have visions of it being a host/hostess gift one evening. Better than a bottle of wine, though hardly the thing you can tuck under your arm.

Made from stone but painted to look like bronze, it sits in the centre of the mantlepiece, providing perspective on the height of the ceiling.

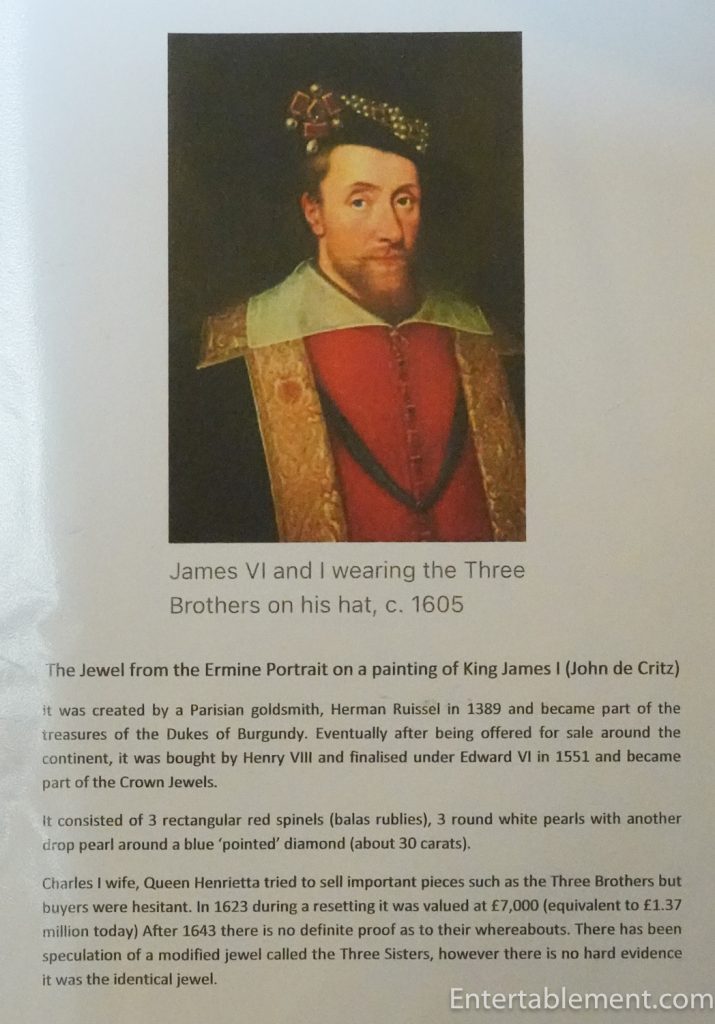

The Ermine portrait of Queen Elizabeth I is named for the little creature on her left arm. It may be connected to a visit in 1585 to Theobalds, which was then home to William Cecil, Lord Burghley, later of Burghley House. She is wearing quite magnificent lace and holding a sprig of olive in one hand, representing peace. The flat light in the portrait makes it a little challenging to appreciate the jewellery she is wearing. Lean in and see the pendant comprising three enormous rubies, known as the Three Brothers, which once belonged to the Dukes of Burgundy.

More on the Three Brothers, who apparently got around!

The Chase Desk, on the opposite side of the room to the fireplace, immediately catches your eye.

It’s a modern piece commissioned by the current Marquess of Salisbury from Mr Rupert Brown.

The continuous scheme of marquetry depicts a boar hunt, which may have occurred in Dorset in 110, soon after Robert Cecil acquired the property. Note all of the different woods that were used to make it!

It took more than 5,000 hours to make. And look at all the different animals in the scene! I was enchanted.

The scene in the modesty panel in the centre of the desk.

The Chinese Bedroom

This room has been substantially altered. It was originally twice its current size and formed part of a suite of rooms set aside for the King. The bed, chimneypiece, and ceiling all date from the first half of the 19th century.

The room is named for the beautiful hand-painted wallpaper. Unfortunately, I didn’t get a shot of the fireplace, which is painted to resemble red lacquer. The theme is extended to the painted cartouches in the ceiling with crests and armorial bearings of the Cecils and related families.

I’m a sucker for intricately carved boxes, and I particularly liked this one. It’s a Chinese ivory workbox carved around 1825 for the 2nd Marchioness.

The Long Gallery

Hold onto your hats. This is the piece de resistance. The opulent ceiling of the Long Gallery, covered in gold-leaf patterns, casts a warm glow over the 170-foot room, one of the longest in any English Country House. It was extended in 1781 by opening up the rooms at each end and inserting tall, wooden pillars.

It wasn’t easy, but by practically lying on the floor, to the annoyance of my fellow tourists, I got a closeup of the ceiling. It was originally white, but the 2nd Marquess, impressed by a ceiling he saw in Venice, had it covered with gold leaf.

The lighted wall cabinet contains these beautiful pieces carved out of rock crystal and decorated with rubies, pearls and gold. They belonged to Robert Cecil, some of which he inherited from Lord Burghley. I would have given my eye teeth for a tripod, but I had to make do with holding the camera as steadily as I could. They’re not crisp shots and don’t do the pieces justice, but you get the idea.

Another fantastic little box with which the house is filled.

The current Cecils are remarkably accommodating to visitors by allowing as much light into the house as they do, even more astonishing as it’s still their family home! I have often been frustrated beyond measure having to grope my way through houses presented by the National Trust, supposedly “in the business” of promoting visitors, but whose “conservation” practices make it as difficult as possible for you to appreciate the interiors.

The North Gallery leads off the Long Gallery, and windows in the panelling on the side overlook the Marble Hall below.

The Winter Dining Room

Now, why didn’t I think of that? A separate dining room with a fireplace to be used in the frigid winter months. Think of the photography!

Originally a bedchamber with an adjoining withdrawing room, in the 1780s, the family knocked the two together. The dining room for the family was used until the First World War. Isn’t it luscious? I wish I’d taken close-ups of the tapestries because they feature scenes from spring, summer, autumn and winter, based on engravings by Martin de Vos.

What I did manage to get, however, were closeups of the china. Of course. I didn’t note down the manufacturer, but I did do a bit of digging around on the internet and here is what it came up with:

The china in these images appears to be 18th-century Meissen porcelain, possibly from the Marcolini period (1774–1814), or a similar Dresden-style floral pattern from another fine European porcelain house. The decoration features hand-painted polychrome floral sprays, delicate scrollwork gilding, and a pink border, a popular Rococo aesthetic.

It went on to say:

The tureen is particularly striking with its figural finial—a sculpted female figure characteristic of Meissen and other German porcelain manufacturers of the period. The green leafy handles are another clue, as they resemble motifs used by Meissen and some other high-end manufacturers like KPM Berlin or Sèvres.

Given the lavish gilding, pink accents, and floral decoration, this set could have been produced for aristocratic or royal tables in the late 18th century. Since the images appear to have been taken at Hatfield House, it is likely part of their historic porcelain collection.

Impressive, no?

Also, note the gorgeous carving on the back of the dining chairs; they’re from the late 18th century and made in China of padouk wood. They were a gift to the 1st Marchioness in 1819.

The Library

More than 10,000 books grace this fabulous room. I could snuggle up in one of those red leather chairs beside a crackling fire and be gone for days. The chairs are from 1782 and were recently recovered in Nigerian goatskin to match the originals.

Like the Winter Dining Room, the library was created in 1782 by removing a dividing wall between the original Great and Withdrawing Chambers on the west side of the house. The rebuilt fireplace contains Robert Cecil’s ” portrait,” which is actually a mosaic made in Venice and presented to him in 1608.

The Adam and Eve Staircase

Though the staircase dates from a century earlier, it takes its name from two pictures of Adam and Eve that hung here in the 18th century. The panelling lining the walls is beautifully carved, with heads at the centre of each panel. It’s a photographer’s dream!

The carved ivory Chinese palace is at the bottom of the stairs. It is so delicate that two men carried it on foot from London in 1786. Can you imagine?

Clearly, killing elephants for their ivory ranks right up there among abhorrent practices. But what’s done is done. We can still appreciate the workmanship of what is considered a diplomatic gift from the Chinese Emperor to King George III.

The Armoury

We pass through this wonderful gallery on the way to the family chapel.

It started life as an open logia in the Italian Renaissance style with a door at the top of the steps at either end. However, this proved inconvenient, as the two wings had no interior ground-floor passage. In 1834, the 2nd Marquess filled in the windows and laid the marble floor. The 3rd Marquess installed the panelling.

We gathered from the very helpful attendant stationed there that the children of the house now use it to ride their bikes on rainy days. You can glimpse the ping-pong table behind the screen and a ball forgotten on the floor. Love it!

The 2nd Marquess purchased most of the armour from the Tower of London in the 19th century. We can only assume they had a surplus.

The face of the figure inside the suit of armour is based on Charles I’s death mask.

The Chapel

Hatfield House’s private chapel is a hidden gem, offering a glimpse into the religious devotion of the Cecil family. The chapel’s dark wood pews, stained glass windows, and regal coats of arms remind visitors that faith and politics were deeply intertwined in the Tudor and Stuart periods. A trusted advisor to the monarchs, the Cecils had to navigate England’s turbulent shifts between Catholicism and Protestantism, and the chapel stands as a quiet testament to the family’s enduring presence through these upheavals.

Here is a clearer picture of the stained glass window behind the altar.

Because we are about to head to St Ethelreda’s Church on the Hatfield Estate, I confined myself to a few pictures of the chapel, including the lovely ceiling. Let’s head to the Victorian Kitchens and then into the gardens.

The Victorian Kitchen

Restored to 1846, when Queen Victoria visited Hatfield House, this room is at the centre of a series of basement rooms designed to service the house. The original kitchen served from 1611 to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939; the house was used as an army hospital during the war.

Lovely copper kettles all lined up are original to the house.

The Still Room maid, under the beady eye of the Housekeeper, made preserves and jams here.

I was very taken with the china pattern on the cups and saucers. “Computer says”:

The autumnal floral pattern was a popular transferware and hand-painted motif in the mid-to-late 19th century. The scalloped rims and ornate handles suggest they are likely Victorian-era Mason’s Ironstone or Staffordshire porcelain.

And who doesn’t love a Harrod’s or Fortnum and Mason Stilton Cheese jar?

The pen and ink style frieze around the walls is cheerful and inviting.

The Gardens

The gardens, originally designed by John Tradescant the Elder for Robert Cecil in the 17th century, provide a lush setting that has evolved over centuries. They retain their historic charm while reflecting changing styles and trends.

Tradescant went to Europe to collect trees, bulbs, plants and fruit trees, many of which had never before been seen in England. The garden included fountains, orchards, water parterres, terraces, pavilions, and herb gardens.

The pleached trees of the Lime Walk were planted in the 18th century to provide a covered walkway, installed by the somewhat chubby 3rd Marquess so he could take some exercise.

Ancient brick walls enclose the Sundial garden on three sides. Roses, ancient and modern, adorn the raised beds.

Elizabeth Opening the Royal Exchange

In one of the pavilions at the end of a walkway is an artificial stone carving by JG Bubb from 1825 depicting Elizabeth I and her courtiers. It was originally installed on the Royal Exchange in London.

The Old Palace Garden

The gardens of Hatfield House adjoin those of the Old Palace, with its spectacular parterre.

The Stables

We began the day at The Old Palace and stopped by the Stables before seeing St Ethelreda’s Parish Church.

There are several enjoyable independent shops besides Hatfield’s gift shop.

We didn’t have the time or energy to visit The Park, Castle Folly, Sawmill, Queen Elizabeth’s Oak Tree, or the Woods, so there is plenty to see on a return visit. Hatfield is only about half an hour from downtown London, though beware of the 20 mph speed traps, which abound!

The Cecils: Guardians of the Realm

William and Robert Cecil were instrumental in shaping England’s political landscape, acting as the power behind the throne for multiple monarchs. William Cecil, Lord Burghley, was the steady hand guiding Elizabeth I, while his son Robert Cecil played a critical role in ensuring the smooth succession of James I after Elizabeth’s death. Hatfield House became more than just a family home—it was a political nerve centre where crucial state decisions were made.

The Cecils’ legacy continued through later generations, with family members advising monarchs through the Civil War, the Restoration, and beyond. Their ability to survive shifting political landscapes is a testament to their diplomacy, discretion, and statecraft skills.

Hatfield House Today

Still owned by the Cecil family, Hatfield House remains a living piece of history, adapting to modern times while preserving its past. The estate hosts tours, events, and film productions, offering visitors a glimpse into its storied past. It continues to symbolize and adapt—much like the Cecils themselves.