In 1603, Queen Elizabeth I died childless. Her cousin, James VI of Scotland, became James I of England (1603-1625), uniting the long-warring nations of England and Scotland. And so the Tudor Era ended, and the Stuart Dynasty began.

The Stuarts believed in the divine right of kings and asserted that God gave them direct authority. This caused constant conflict with Parliament over finances and authority, in addition to the ongoing religious strife between Protestants and Catholics.

James VI/I, a scholarly and practical ruler, brought us the King James Bible in 1611.

A patron of the famous architect Inigo Jones, James could not have foreseen the gruesome site his Banqueting House would witness.

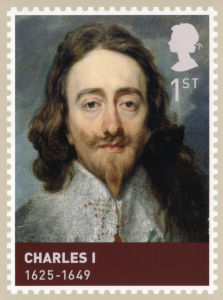

In the mid-seventeenth century, a bloody civil war erupted between the Crown (Cavaliers) and Parliament (Roundheads). Authors Sellar and Yeatman describe the factions in their satirical book, 1066 And All That: A Memorable History of England as the Cavaliers: Wrong but Wromantic and the Roundheads: Right but Repulsive.

The Parliamentarians prevailed and executed King Charles I outside the Banqueting House in London in 1649. The crowds groaned.

Oliver Cromwell came to power and ruled for the decade-long Interregnum. His strict military command created national stability, but it was a joyless regime.

A raft of pamphlets spread revolutionary ideas far and wide. Though a radical Puritan, Cromwell was more tolerant of other religions than frivolity.

His unpopular regime ultimately collapsed, leading to the Restoration of the Monarchy.

After England’s brief flirtation with a republic, Charles II returned from exile and ruled over a scandalous court. But theatre, art, and architecture blossomed.

Printers produced books, pamphlets, and newspapers in abundance. John Milton wrote Paradise Lost) and John Locke philosophized on politics, emerging as influential thinkers of the burgeoning Enlightenment.

London recovered from the Great Fire of 1666, using the opportunity to build more modern structures.

Sir Christopher Wren did more than rebuild St. Paul’s Cathedral. As Professor of Astronomy, Wren’s lectures prompted twelve men of science to form a “College for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematical, Experimental Learning” at Gresham College, London.

This group was later known as the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, or what we would now call science. As one of the founders, Wren believed that the Society should transform knowledge, profit, health, and the conveniences of life. Today, it continues as the oldest fellowship of many of the world’s most eminent scientists.

After Charles II’s death, his brother, James II, acceded to the throne. His conversion to Catholicism in 1669 cast a deep shadow of suspicion regarding his religious loyalties. His heavy-handed efforts to promote Roman Cathoisms fomented conflict with Parliament. But his son’s birth in June 1688 really set the cat among the pigeons.

Fear of a Roman Catholic dynasty alarmed his subjects, whose memories of bloody religious strife were all too fresh.

In no time flat, James II was deposed in what is known as “The Glorious Revolution”.

James II was quickly replaced. His Protestant daughter, Mary II (1689–94) and her Dutch husband, William III (1689–1702) were invited to rule jointly. A largely peaceful period ensued for England.

The Act of Settlement was passed in 1701 to ensure that the throne would henceforth be in Protestant hands.

Mary’s sister, Anne, succeeded in 1702 and ruled until 1714.

The most significant political event of Anne’s reign was the Act of Union with Scotland (1707), which created a unified Great Britain.

The Duke of Marlborough battled Louis XIV of France and won. A grateful nation gifted him Blenheim Palace, designed by John Vanbrugh in the period’s popular Baroque style.

Sadly, though Anne had eighteen pregnancies, none of her children lived to maturity, leaving the succession up in the air. Again.

To the chagrin of 57 Catholic claimants to the throne, George, Elector of Hanover, was next in line.

For the next half-century, James II, his son James Francis Edward Stuart, and his grandson Charles Edward Stuart agitated and fought to be recognized as the true Stuart kings. This caused no end of grief and ended disastrously for Scotland.

The Stuart Dynasty ended with Anne’s death and King George I’s accession from the German House of Hanover.

The Stuart Monarchs ruled through political upheaval, social evolution, and cultural flourishing. The Georgian Era was even more lively. Hold on to your hats—there’s a lot more to come!