Hidcote Manor Garden is one of Britain’s best-known Arts and Crafts gardens. Its fame is all the more astonishing as the stunning masterpiece was not designed by a professional landscape architect but by an amateur with a tremendous interest in plants and garden design.

Though Lawrence Johnston was born in Paris in 1871 as the son of a wealthy Bostonian stockbroker, he was technically an American. He became a naturalized British subject in 1900 after graduating from Trinity College, Cambridge University.

He joined the Imperial Yeomanry and was posted to South Africa, where he fought in the Second Boer War. While in South Africa, he developed an avid interest in their native plants. His expertise grew to the extent that the Royal Horticultural Society elected him as a fellow in 1904.

In 1907, Lawrence purchased Hidcote on behalf of his now re-married mother. Mrs Gertrude Winthrop. Located near the village of Hidcote Bartram, from which the property’s name derives, the 297-acre property came with a ‘very substantial and picturesque farmhouse… with lawns and a large kitchen garden’, according to the sale advertisement in The Times, dated June 22, 1907.

Now retired with an ample income, he began to design and build linked garden rooms separated by hedges, rare trees, shrubs and herbaceous borders employing principles he learned through reading The Art and Craft of Garden Making by Thomas Mawson. His plans encompassed ten acres surrounding the (now enlarged) farmhouse at Hidcote. Although the house had a large kitchen garden, the rest of the property was a blank canvas.

Johnston had plenty of like-minded enthusiasts nearby. He became close friends with Heather Muir, who, with Diana Binny and Anne Chambers, created the feminine, romantic gardens of Kiftsgate Court. Edith Wharton, lover of Italian gardens, was also a local resident. A further influence on Hidcote’s design came from Gertrude Jekyll, a proponent of single-colour garden rooms, described in her book Colour in the Flower Garden, published in 1908.

The Cotswolds were something of a magnet for British and ex-pat American artists and composers in the early 20th century. Impressionist artist John Singer Sargent, British composers Edward Elgar and Ralph Vaughan Williams and author J. M. Barrie were among them. Most influential for Lawrence Johnston was the great Arts and Crafts designer William Morris of Kelmscott Manor, which we visited last fall (blog to come).

Arts and Crafts gardens take an approach to design that combines symmetry, vistas and axes to include the surrounding landscape, clearly evident at Hidcote.

Natural materials are prominent, comprising stone or gravel for paths, low walls, timber structures and wrought-iron gates.

We find strong geometric shapes also prevalent in medieval and early Renaissance times. At Hidcote, formal hedges outline squares and rectangles filled with a cottage-style abundance of plants, a technique Gertrude Jekyll often used in her designs.

Hedges form garden room enclosures, including the tapestry hedge Johnston planted. Among the first of its kind, it incorporates a variety of plants instead of a single species. Other hedges are of traditional English yew.

Hidcote’s central gardens form two main axes, which are a little hard to detect in the diagram below.

Plan of the garden. 1 Entrance, 2 White Garden, 3 Long Walk, 4 Red Borders, 5 Fuchsia Garden, 6 Bathing Pool Garden, 7 Theatre Lawn, 8 Stilt Garden, 9 Pillar Garden.

The 400-foot Theatre Lawn (7) forms the shorter axis, enclosed in 7′ Yew hedges. It runs from the rear of the Manor House.

The long axis (3) comprises the 600-foot narrow Long Walk. On either side is an array of small garden rooms, each with a different theme. They are enclosed by various hedges and flanked by deciduous Hornbeam hedges.

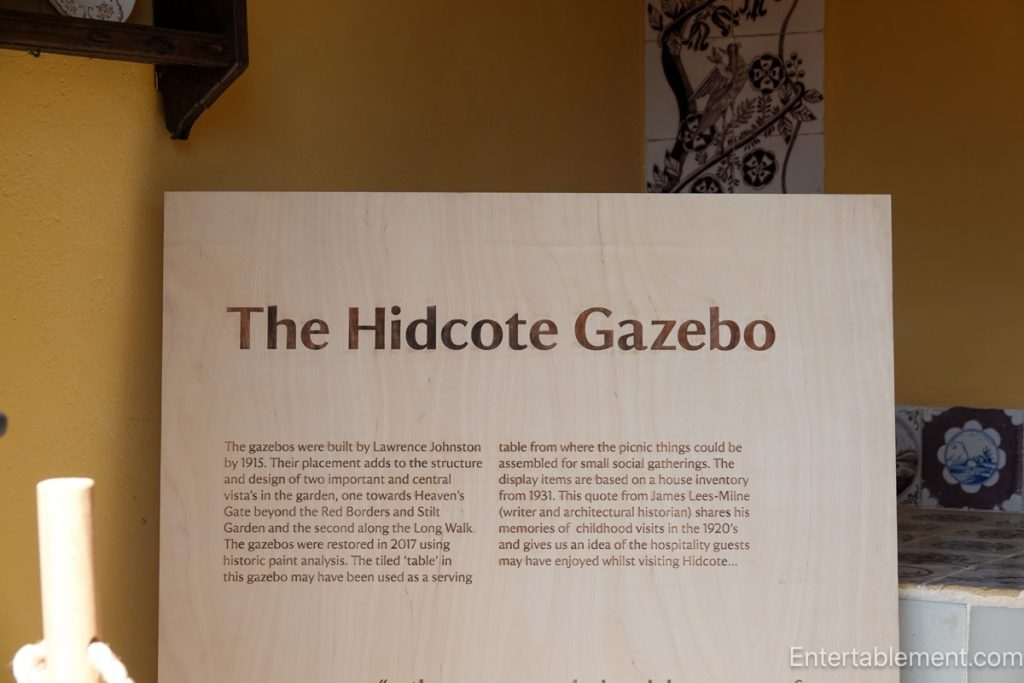

At the junction of the Long Walk and Theatre Lawn is a pair of gazebos—a focal point which invites the viewer to stroll up the lawn to explore what might be inside.

Let’s peek inside the gazebos.

Behold! A tiled “table” with some tea accoutrements is handy for serving refreshments to guests. Tea anyone?

Magical.

Delightful vistas wherever you look. Note the palm tree over on the left. Johnston was quite a collector of exotic plants.

Single-colour garden rooms include a White Garden (2) and the Red Borders (4).

Hedges raised on clean trunks feature in the imaginative Stilt garden (8).

The Bathing Pool garden (6) is surrounded by clipped hedges, which incorporate some bird topiaries.

Live birds enjoy the water in the central pool.

A natural stream runs across the property and includes woodland areas, which surround the core of the gardens.

This masterpiece of space and colour has more than twenty distinct parts.

The working areas, the kitchen garden and the Rose Garden adjoin the house.

The First World War paused Johnston’s plans, as they did for the entire country. Major Johnson fought in Flanders, and after hostilities ended, he returned to his garden. Undoubtedly, it provided much balm for his soul after the horrors of the trenches.

As the garden progressed, Johnston hired Frank Adams as his Head Gardener (formerly of Windsor Castle). Together, they scoured the Chelsea Flower Show for inspiration, collaborating on which ideas to implement and which plants to add. The gardening team swelled to twelve full-time gardeners during the 1920s. This is not such a large number when you consider the absence of power equipment and tools.

Johnston became especially interested in rare plants and frequently visited the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, Surrey. Alpine plants were in fashion then; he grew hundreds of them for his rock garden. He travelled further afield, joining famed plant collector George Forrest in a plant-collecting expedition to Yunnan, China. He also funded expeditions by other collectors. Indeed not a man who languished in his retirement.

In 1924, he acquired Jardin Serre de la Madone in the south of France. He spent more and more time there until he died in 1958. Also restored, it is open to the public.

Public interest in Hidcote began when Country Life Magazine published two articles on Hidcote in 1930, followed by a radio show hosted by famous designer Russell Page. Despite his retiring nature, Johnston began to open the garden in a limited way to invited visitors.

NOTE before I forget…Country Life is a fabulous magazine whose raison d’etre is described on their site as … the quintessential English magazine… comments in depth on a wide variety of subjects, such as architecture, property, the arts, gardens and gardening, the countryside, schools and wildlife.

Published weekly (!!), I used to subscribe to the print version before discovering it’s included in the thousands of magazines available through Readly. One app, $12.99 per month. Unbelievable.

Now, back to our regularly scheduled program.

In 1948, Hidcote Manor was acquired by the National Trust, founded in 1896 to protect and promote the English landscape and, later, its architecture.

Lucky Hidcote was cared for by National Trust’s garden consultant, the famous gardener and author Graham Thomas, for many years. More recently, the gardens have been restored to return the plantings as much as possible to align with Johnston’s original intentions. It now reflects the more flamboyant taste prevalent in the Edwardian era to which he belonged, incorporating tropical plants and colourful annuals.

Hidcote was to prove a tremendous influence on gardens that followed it, most notably at Sissinghurst, the garden created by Vita Sackville-West and her husband Harold Nicholson in the 1930s. Order, produced by lines and hedges, combined with informal planting, became the dominant theme of British, and to a lesser extent North American, garden design for most of the 20th century.

The Room Outside, by John Brookes, was inspired by Hidcote and promoted a small-scale version of Johnston’s approach. It is arguably one of the most influential garden books of the last decades of the 20th century.

Lavandula angustifolia ‘Hidcote’, or Hidcote Lavender, is growing widely today. It lines the border of my curving (sorry, Johnston) front path. It’s looking a little scraggly, but it will bloom gloriously in a few weeks.

Hidcote’s sweeping vistas are readily evident in the YouTube video by the National Trust. What you can see from above is impressive, thanks to drones!

It’s genuinely one of the great gardens of England, and I enjoyed every minute of the visit.

.

Dear Helen, I never got a chance to see Hidcote, but I too grew the lavender when I had a big garden. Your pictures give a nice overview of the layout and intent, and I love the fritillaria! I have always thought that if I ever won the lottery, the first thing I would do is hire a masseuse, a flower valet, and several gardeners. So many beautiful gardens in the Cotswolds…thanks for the memories.

The fritillaria were delightful! Don’t you love that a flower with a chequered pattern occurs in nature?

I’m with you on the wish list for everything but the masseuse. 🙂