From the outside, the Pantheon is frankly unprepossessing. A heavy cylinder with a classical porch awkwardly grafted on. It bears a striking resemblance to a hedgehog house with columns. And then there is the inscription on the portico—M·AGRIPPA·L·F·COS·TERTIVM·FECIT.

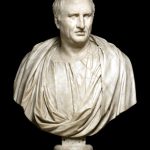

The inscription credits Marcus Agrippa, who built an earlier Pantheon in the first century BCE. The structure we see today was almost certainly rebuilt under Hadrian — who could easily have taken credit. He didn’t. He left Agrippa’s name in place.

Nothing about it suggests what waits inside. If you didn’t already know its reputation, you might walk straight past without a second glance. And if someone wonders why the porch’s rafters are bare, that’s part of the building’s story too — its materials have played more than one role in Rome’s architecture, quietly circulating into other places of power.

Inside, everything changes. The space opens upward, light moves across the dome, and time becomes visible. Standing inside — where the oculus is a nine-metre circle of sky — the building doesn’t feel large so much as complete, like a thought drawn in space.

People instinctively slow down and lower their voices. The officials don’t demand silence, but reverence seems to produce it.

On a visit several years ago, we were there with three other couples. One of them was in the midst of what you might generously call marital tension. She was a forceful woman, full of ideas, and as she took in the space she announced—brightly, decisively—that this would be the perfect place to renew their wedding vows.

At that suggestion, her husband’s expression changed completely. He went very still. His eyes widened. His mouth tightened. He looked, unmistakably, like a stuffed frog.

Later, we learned that he left her shortly after the trip, taking up with his secretary. When the wife discovered this, she marched into the office and threw a cup of hot coffee on said secretary.

One suspects the Pantheon would have made room for that scene as well. The building is remarkably accommodating.

That accommodation is not accidental. The Pantheon was built as a temple to all the gods, but Romans did not worship inside temples the way later traditions would. Ritual happened outside. The building itself was a house—for forces, for order, for the idea that the universe could be enclosed, measured, and held.

The dome still feels improbable. Its open oculus admits light, air, and rain, which falls onto a subtly sloped floor and disappears through drains set into the stone.

The structure works because it is intelligently uneven. The concrete is heavier at the base, lighter as it rises, thinned and relieved by coffers that reduce weight.

Roman concrete is one of the quiet marvels of the ancient world. Mixed with volcanic ash, it continues to strengthen over time, forming crystals that heal small cracks rather than widening them.

Modern concrete cures and slowly degrades. Why, you ask, are we not using Roman technology? Beats me.

Even the Pantheon’s losses feel Roman. In the seventeenth century, the bronze beams of its portico ceiling were stripped on papal orders.

The bronze was reused to create Baldacchino in St Peter’s Basilica, designed by the magnificent Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

When Michelangelo studied the Pantheon while designing St Peter’s Basilica, he wasn’t asking, How do I make something beautiful? He was asking, How do I make something this big stand?

He famously said ““I will build such a dome that will hang in the air.” And then he went and studied the ancient Romans — because they already had.

Bernini himself embodied that confidence: expansive, theatrical, perfectly attuned to power and scale. Famous for the moment in his statues, one of his critics was known to ask where all the wind was supposed be coming from.

His great rival, Francesco Borromini, was something else entirely—intense, inward, mathematically obsessive. Where Bernini worked comfortably at imperial scale, Borromini folded astonishing complexity into tight spaces, most beautifully in his small church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane.

Bernini persuaded; Borromini argued, and Rome had room for both men. More on their famous rivalry when we get to the post-reformation era.

The Pantheon has outlived the religion that built it, the empire that funded it, and the political system that made it possible.

It survives not because it was sacred, but because it was useful. It solved a problem — how to enclose vast space, distribute immense weight, and endure — and it solved it well enough that later centuries saw no reason to undo it.

At some point it was converted into a church, a decision that almost certainly saved it. But what’s remarkable is how little the building itself had to change. The gods were swapped out; the structure remained.

Standing inside the Pantheon, it’s hard not to think about how much of modern life is built the other way around — optimized for immediacy, visibility, and speed. The Pantheon was built to last, not to impress, and in the long run it has managed to do both.

And in doing so, it offers a quiet reminder that human drama is fleeting, human nature is constant, and that once in a while, good systems really do outlast us all. Two thousand years on, people are still standing beneath this dome — arguing, wondering, proposing, doubting — inside a universe made legible without explanation. And if you find yourself looking up on your own first visit, I doubt you’ll be surprised.

I learn so much from you! Thank you for this.

It’s my absolute pleasure. Thank you for taking the time to comment! I blather on and send things out into the digital universe – who knows if people find it helpful, annoying or what? I appreciate the effort!

You should be a teacher. You make history so interesting. When we were in Rome, we walked right by this building…and now I’m sorry we did.

Who wouldn’t? It doesn’t look like much, does it? I can’t take the credit. Not only were our kids terrific on that first day, we then hired an amazing guide on subsequent trips. You could spend a month and not even scratch the surface. I think better and pay more attention with a camera in hand — there is something about searching for the detail for framing that helps make the switch. So glad you enjoyed!

Seeing these beautiful pictures of St Peter’s Basilica made me feel that I was at Sunday mass. We’ve been there many times and looking at the pictures that I took many years ago never cease to amaze me of all the time it must have taken to build these structures and the length of time that they have endured. Magnificent writeup! Thanks for this fascinating story of history.

It is astounding, isn’t it, Maura? I adore England, as you know, but Rome has so many layers of history in quite a concentrated area. We are very lucky to have seen so much of it!