This essay is part of The Continental Thread — a series exploring how authority, culture, and daily life reorganized themselves as Europe moved from Roman order to the modern world.

My first trip to Rome included our son Adam and his then-fiancée Annie. They had both been before—Annie in particular is travel-obsessed in the most admirable way—and they undertook to show us Rome in a single day.

Though (probably because) we were neophytes, Glenn and I were game.

It became clear fairly quickly, though, that we were not approaching the day in quite the same spirit. Annie made no plans to stop for meals. We would eat standing up, as needed, on the street. Rome, efficiently consumed.

Glenn was having none of that. To him, life is punctuated by sit-down meals and beer, taken slowly. Food is not a refuelling stop; it’s part of the structure of the day.

What followed was a gentle but unmistakable recalibration. Annie hopped with impatience; we moved more slowly. But we all enjoyed a sit-down lunch, with two courses and wine.

And somewhere in that adjustment, Rome began to reveal itself—not as a checklist of sites, but as a city capable of carrying people through long days, provided you were willing to accept its rhythm rather than impose your own.

The next morning, we saw them off in a taxi. They had planned to take the bus. Annie urged us, cheerfully, to go and visit the Vatican.

We went back to bed.

Only later did I realize how Roman that experience was.

After Greece, Rome feels different almost immediately. The air seems heavier, the stone thicker, the spaces less interested in conversation than in movement.

Where Greece asks you to participate, Rome offers something closer to relief—the sense that decisions have already been made, that the day can proceed without argument.

You don’t need to persuade anyone, but simply move along.

What I realized in time, was this change in focus was a response to scale.

It took me a while to see that Rome wasn’t trying to quash debate — it was simply doing a different thing with it. It discovered, early and decisively, that persuasion alone doesn’t feed cities, move armies, or defend borders.

The Vittoriano, or Altare della Patria, rising above Piazza Venezia; Rome’s most controversial monument — impossible to miss, whether you love it or not.

Persuasion morphed into a technology of governance, not open, endless debate like the Greek polis. People such as Marcus Tullius Cicero emerged, famous for his faultless rhetoric, who could argue well on behalf of others within a system of offices, procedures, and precedent.

(Foreboding music: enter the politician and the lawyer).

An empire cannot rely indefinitely on goodwill or consensus. Eventually, it needs systems—repeatable, enforceable, and largely indifferent to the temperament of the individuals passing through them.

Rome didn’t invent most of the ideas it used. It absorbed them. What it perfected was logistics.

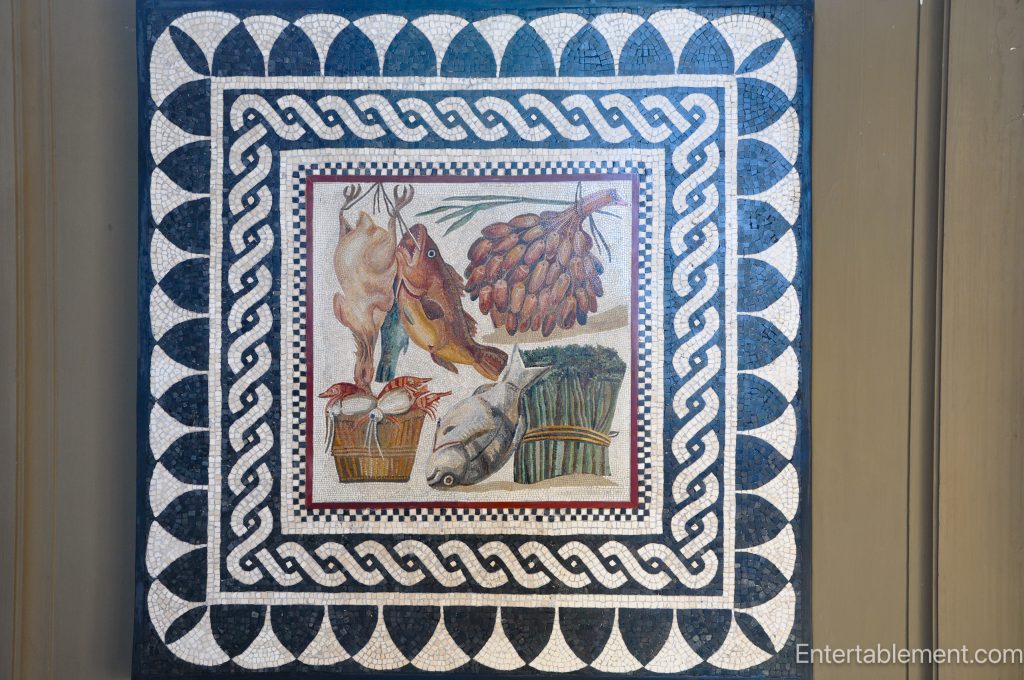

Food makes this especially clear. In Rome, eating ceased to be primarily ritual or social expression and became infrastructure.

Grain crossed seas, storage facilities multiplied and bakeries scaled production. Distribution was organized, monitored, and politically charged.

When food arrived on time, the city remained calm. When it didn’t, unrest followed quickly. Low blood sugar “hangry” on an industrial scale. Because food distribution isn’t just logistics — it’s security, identity and community. Food matters on so many levels.

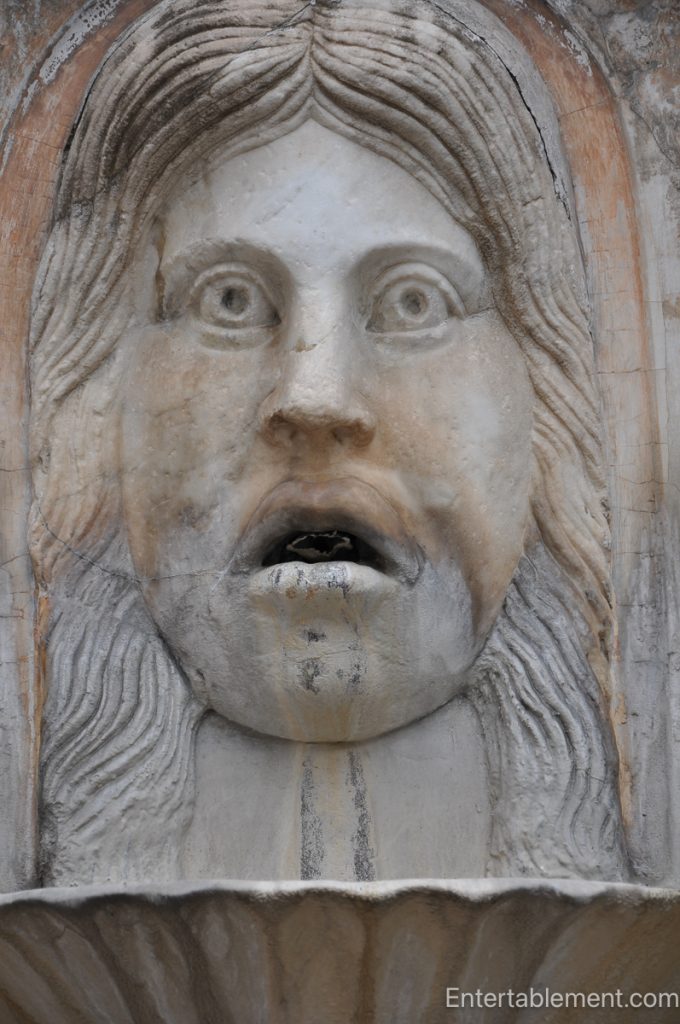

Between public logistics and private houses lay another Roman system: the baths. Roman baths were semi-public spaces for embodied relief — heat, water, and predictable order for bodies worn down by scale. Neither political assemblies nor private rooms, they held people collectively in a system that felt manageable.

And when Rome exported this institution — from Italy to Britain in places like Bath — it exported comfort and a template for communal life at scale.

Domestic life followed the same logic. At places like Herculaneum, the contrast is stark. Wealthy households had kitchens, storage rooms, servants, and space.

Many urban households had none of these things. They relied on street food, communal ovens and prepared meals.

Comfort varied widely, but efficiency was not optional. Scale produces stratification whether or not anyone intends it to.

Infrastructure became the most visible expression of Roman power. Roads carried troops and grain across distances that would have broken earlier civilizations.

Aqueducts delivered water reliably and in quantities that still feel astonishing.

Latrines managed waste. Amphitheatres absorbed crowds and redirected energy.

These weren’t benevolent gestures in the modern sense; they were stabilizers—the quiet work of keeping things from coming apart.

Where the Greek Agora gathered voices, the Roman Forum organized movement. It was a place to pass through, not linger in—a civic space shaped less by conversation than by procession.

What struck me was how Rome’s decisiveness didn’t ask to be loved — and how that could feel uncaring.

Inevitably, once complexity reaches a certain point, choice itself begins to look less like freedom and more like a liability. And for a long time, this worked.

Rome’s eventual strain is often explained through excess—spectacle, cruelty, slavery, emperors like Nero or Caligula. These things are real, and make for some very unpleasant reading.

But they were more symptom than cause.

Rome strained because the pendulum swung too far. The systems that held the empire together grew vast, expensive, and increasingly brittle.

Maintenance costs rose as oversight weakened. Legitimacy depended entirely on continued delivery. Overreach didn’t announce itself as failure; it felt like abundance.

There were moments of restraint. The so-called “good emperors” are remembered less for vision than for stewardship. Figures such as Hadrian consolidated rather than expanded.

They invested in administration, understanding that continuity required limits.

Rome’s achievement wasn’t the creation of a perfect civilization. It was the creation of one that could endure at scale—by reducing reliance on individual virtue and increasing reliance on systems.

That trade-off brought water, bread, roads, and relative stability. But it also introduced distance, hardness, and a kind of moral numbness.

Greece placed human nature in full view—argued over, performed, contested in public. Rome built systems to manage that same nature in large numbers.

What neither could change was the human nature itself. We are still impatient, still local in our thinking, still quick to forget yesterday’s miracle when today’s expectation goes unmet.

Sometimes someone has to decide. Rome decided early and often. For a long time, everyone else lived with those decisions.

That decisiveness brought relief—and, eventually, strain. When the systems could no longer bend, they broke.

Not all at once. Not dramatically. But persistently enough to change the shape of the world that followed.

What Rome exported was more than power; it exported ways of inhabiting authority. We see this in roads and aqueducts, in houses that borrow Roman plans in Asia Minor, in baths across Europe, and in urban grids that echo Roman logic. Wherever these templates took root, they carried a lesson: systems make large numbers livable, and private relief is not withdrawal but continuation of the civic project in a different key.

What remained were the roads, the ruins, and, in walking them, a lingering understanding of what expansion can achieve—and what it costs. Rome gave relief, and demanded it back. That, more than the stones themselves, is what lingers.

Nowhere is Rome’s faith in systems clearer than in the Pantheon, a building that still stands because it was designed to work, and its purpose changed with time.

Its massive dome still feels improbable, impossible even, but there it is, with its unremarkable, even ugly, exterior.

Michelangelo is said to have studied it while working on the dome of St Peter’s, not to imitate its beauty so much as to understand how it solved the problem of scale.

The Pantheon endures because it was designed to work—to distribute weight, to manage forces.

And like Rome itself, to last.

- Previous in the series: Greece—When Life Moved Into the Open

- Next in the series: Collapse, Scarcity, and Survival—When Rome Leaves the Room

- Related post: The Pantheon