Let’s start with the backdrop: the English Civil War (1642–1651), a brutal and bewildering conflict that split families and the kingdom alike. On one side were the Royalists, or Cavaliers — the aristocratic, flamboyant defenders of King Charles I. Think of them as described by W. C. Sellar and RJ Yeatman in 1066 and All That: “Wrong but Wromantic” — dressed in fine lace, riding horses with plumes, and championing a divine monarchy that seemed increasingly out of touch.

Opposing them were the Parliamentarians, or Roundheads — often dour, Puritanical types who believed in limiting the king’s power and reforming society. They were “Right but Repulsive” — serious, grim, and unyielding, led by men like Oliver Cromwell.

Not to be confused with Thomas Cromwell

Though they share a surname and both played pivotal roles in England’s religious and political upheavals, Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658) and Thomas Cromwell (c. 1485–1540) were not closely related. Thomas was Henry VIII’s chief minister and architect of the English Reformation.

Pragmatic and Merciless

Oliver Cromwell, a relatively obscure Member of Parliament before the war, quickly emerged as a brilliant military commander. He organized and led the New Model Army, a disciplined and highly motivated force committed to the Parliamentarian cause — and to what they saw as God’s will. Cromwell’s soldiers believed they were on a divine mission, and he himself was convinced he was God’s instrument.

Cromwell was a tactical genius and a ruthless leader. Not a romantic hero — he was pragmatic and merciless when needed.

His impact went beyond the battlefield. As part of Puritan ideology, he oversaw or at least condoned widespread iconoclasm — the destruction of what Puritans saw as idolatrous religious imagery. Cathedrals suffered grievously: Ely Cathedral’s Lady Chapel, once a jewel of medieval craftsmanship, was desecrated beyond recognition. Statues, stained glass, and altars were smashed or defaced, an assault on centuries of sacred art and ritual.

Similarly, many castles and fortifications, such as Sudeley Castle, were “slighted” — deliberately damaged to prevent their future military use.

“Slighting” is a typically understated English term that masks the brutal reality of tearing down walls, filling in moats, and rendering these historic strongholds unusable. Cromwell’s campaigns reshaped the physical landscape of Britain in ways that echoed his unyielding religious and political vision.

Many royal and noble tombs were vandalized or desecrated as symbols of the old order. Catherine Parr’s tomb at Sudeley Castle was among those damaged — her effigy was defaced, reflecting the Puritans’ iconoclastic zeal against perceived idolatry and the monarchy’s legacy.

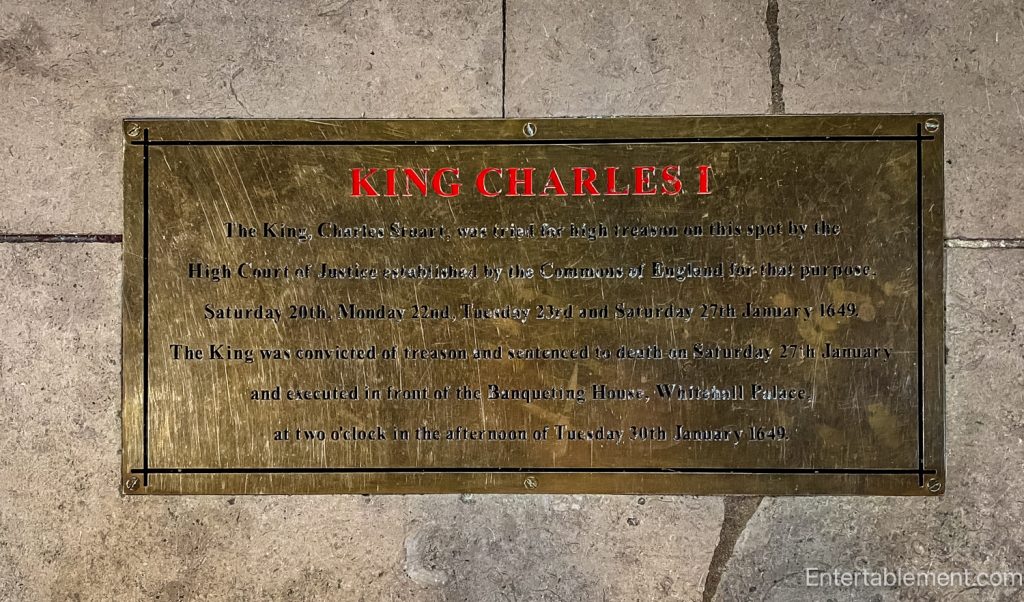

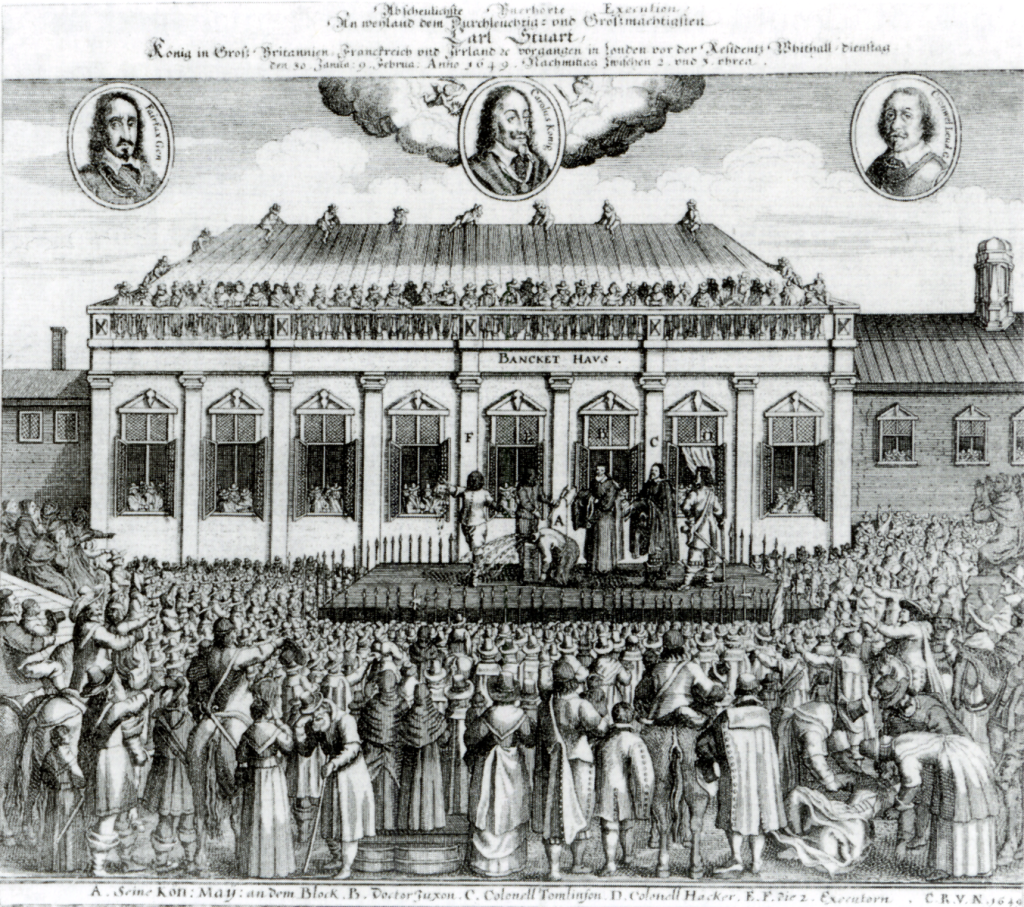

The war ended with the trial and execution of Charles I in 1649, a shocking act that sent tremors across Europe.

England became a republic—or more accurately, a Commonwealth—with Cromwell as Lord Protector. He ruled as a military dictator, enforcing strict Puritan morals and crushing opposition.

While his reign was harsh and joyless, it also set important precedents for parliamentary sovereignty and religious toleration (to a degree). The irony? Cromwell fought tyranny only to become a tyrant himself, wielding power with divine conviction.

His son Richard, unlike his father, lacked the drive and vision. His brief, ineffective rule opened the door to the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, ushering in Charles II, who might have been a dissolute party animal, but at least brought some much-needed levity back to the throne.

The Final, Gruesome Act: Cromwell’s Posthumous Trial

Cromwell’s story doesn’t end with his death in 1658. When the monarchy was restored in 1660, the new regime wanted to make a statement. Though Cromwell was long dead and buried in Westminster Abbey, his body was exhumed, subjected to a posthumous trial, and executed all over again — a symbolic act of ultimate retribution.

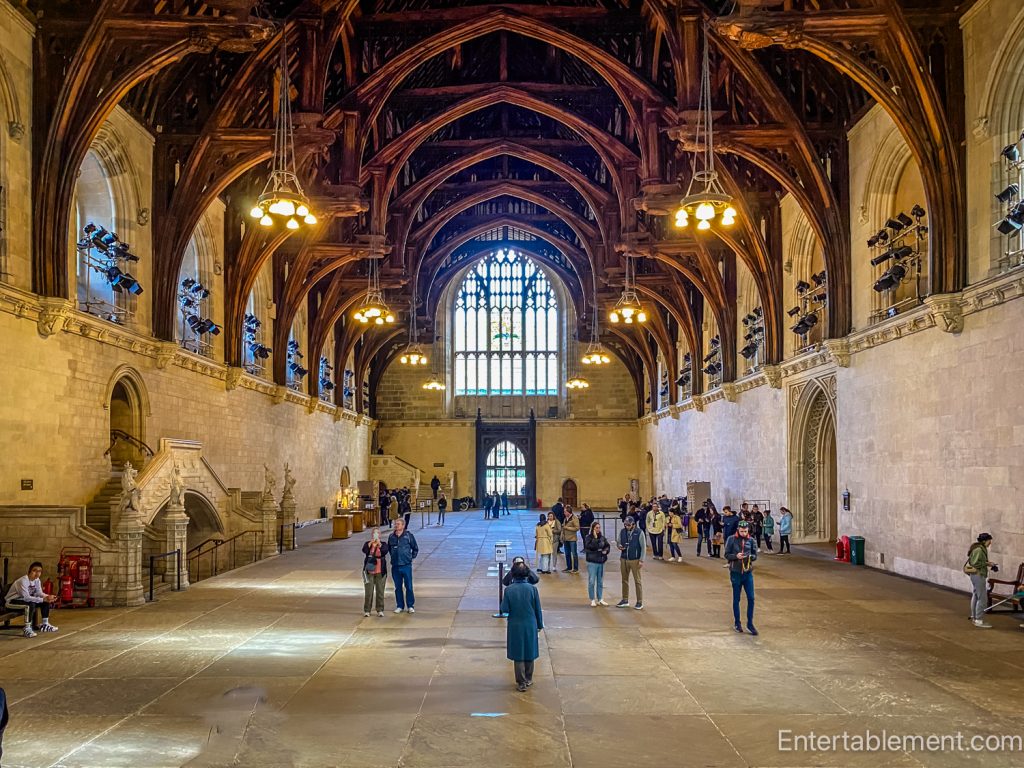

His corpse was hanged in chains, then beheaded — his head displayed on a spike outside Westminster Hall for over two decades. This grotesque spectacle was a stark message: no one, not even a self-proclaimed godly ruler, could escape judgment.

This grim fate echoes the medieval tradition of punishing the dead as a warning to the living — a dramatic example of how justice was as much a performance and spectacle as fairness.

Cromwell’s life and death perfectly illustrate the violent interplay of power, faith, and punishment in Britain’s past — a reminder that history’s heroes often wear complicated masks.