Early Life and Education

Christopher Wren was born in 1632 in East Knoyle, Wiltshire, into a well-connected and scholarly family. His father was the Dean of Windsor, and his early education was influenced by exposure to both the church and academia. Wren attended Wadham College, Oxford, where he excelled in mathematics, astronomy, and physics. Initially, his career path seemed destined for the sciences, and he made significant contributions to anatomy, optics, and engineering before turning to architecture.

Transition to Architecture

Wren’s architectural career began somewhat later than many of his contemporaries. His scientific expertise and problem-solving abilities made him an ideal candidate for designing structures that combine elegance and technical innovation. He was deeply influenced by classical and Renaissance architecture, particularly the works of Palladio, as well as contemporary French and Italian architects. His mathematical precision and scientific understanding of materials allowed him to push the boundaries of structural engineering.

The Great Fire of London and St. Paul’s Cathedral

The Great Fire of London in 1666 proved to be a turning point in Wren’s career. As Surveyor-General of the King’s Works, he was entrusted with rebuilding many of the city’s most important churches. His masterpiece, St. Paul’s Cathedral, was completed in 1710 and remains one of the most iconic buildings in Britain. Inspired by St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the cathedral’s massive dome showcased Wren’s genius for blending classical and baroque influences with structural ingenuity.

Major Works

Wren’s architectural contributions extended beyond St. Paul’s, encompassing public buildings, royal palaces, and over 50 churches across London. Some of his most significant works include:

- St. Paul’s Cathedral, London (1675–1710) – His magnum opus and a defining symbol of London.

- Royal Hospital Chelsea (1682–1692) – A home for retired soldiers, demonstrating Wren’s ability to create practical yet beautiful spaces.

- Hampton Court Palace (1689–1694, expansions) – Redesigned portions of the palace for William III and Mary II, integrating Baroque elements.

- Greenwich Hospital (1696–1712) – A grand riverside structure with magnificent colonnades designed for the Royal Navy.

- Wren’s City Churches (1670s–1700s) – Including St. Bride’s, St. Mary-le-Bow, and St. Stephen Walbrook, exemplifying his signature domes and innovative use of space.

Innovations and Architectural Style

Wren’s work is best characterized by his masterful blend of Baroque grandeur, classical proportion, and engineering brilliance. He introduced dramatic domes, elegant colonnades, and spacious interiors, emphasizing light and balance. His designs often featured:

- Mathematical precision – His background in geometry informed his symmetrical layouts and dome construction.

- Structural innovation – He utilized advanced engineering techniques, such as the double-dome structure in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

- Classical and Baroque influences – Merging elements of Renaissance symmetry with the theatricality of Baroque design.

Personal Life and Legacy

Wren was known for his meticulous work ethic and dedication to his craft. Though knighted in 1673 for his contributions, he remained modest and deeply engaged in architectural problem-solving until his final years. He served as Surveyor of the King’s Works for nearly 50 years, shaping London’s skyline for generations.

However, political changes in the early 18th century led to his dismissal in 1718. With the accession of George I in 1714, the Whigs consolidated power, and Wren, seen as a Tory and closely associated with the Stuart monarchy, fell out of political favour. Additionally, administrative reforms aimed at modernizing the Office of Works resulted in the removal of ageing officials, including Wren, who was by then in his 80s. He was replaced by William Benson, an inexperienced politician whose appointment was widely seen as an act of favouritism rather than merit.

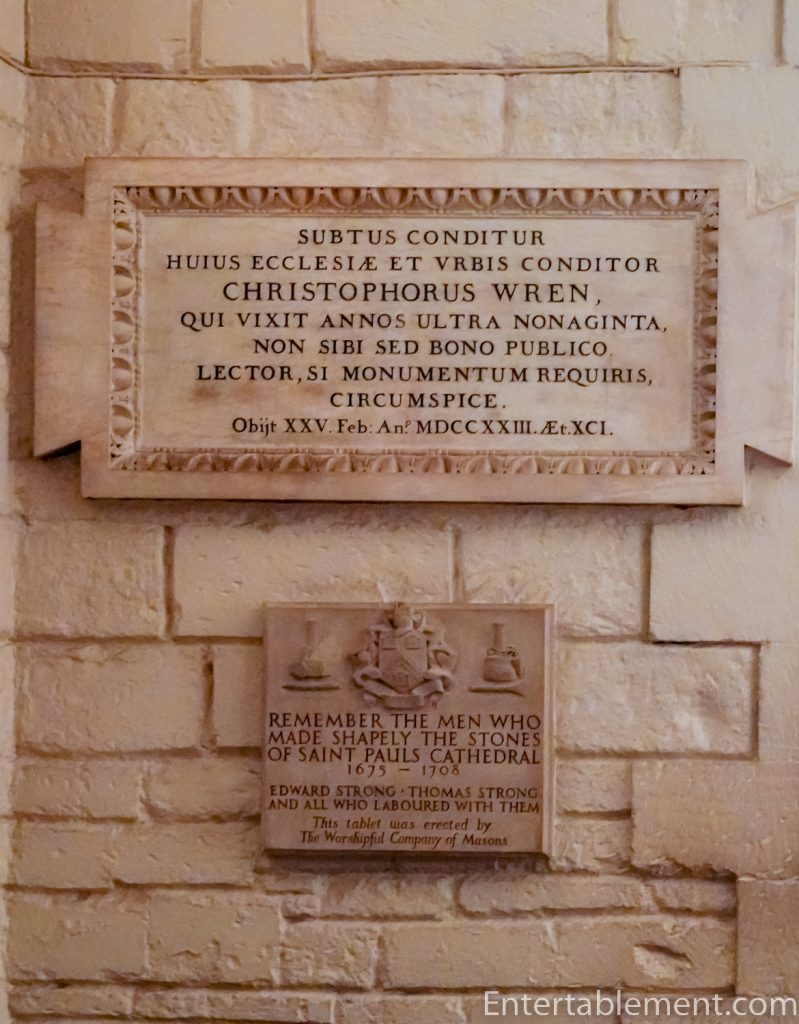

He spent his final years in relative obscurity, yet his legacy was already cemented. He died in 1723 at 90 and was buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral. His epitaph reads: “Si monumentum requiris, circumspice.” (If you seek his monument, look around you.)

Did You Know?

Wren was instrumental in founding the Royal Society, a scientific institution dedicated to advancing knowledge.

- His original design for St. Paul’s Cathedral was far more classical, but he adapted it to suit the tastes of the Baroque era.

- His son, Christopher Wren Jr., was also an architect and helped oversee some of his father’s later projects.

- Wren conducted experiments on materials and acoustics, including early studies on the physics of sound in domed structures.

Christopher Wren’s work remains a defining part of British architectural heritage. His buildings, notably St. Paul’s Cathedral, continue to inspire and demonstrate his vision and ingenuity.