Updated in May of 2025 with new pictures and insights.

It’s easy to see why the Château de Chambord is one of the most photographed châteaux in France. Its roofline—bursting with cupolas, turrets, towers, and chimneys—resembles an entire cityscape etched in stone.

This extravagant architectural flourish marks Chambord as a marvel of the French Renaissance. And yet, for all its grandeur, it was never a true home.

A Palace for the Hunt

Built under the reign of King Francis I, Chambord was conceived as a hunting lodge. An enormous, gloriously impractical hunting lodge.

It boasts 440 rooms, 282 fireplaces, and 84 staircases, yet the king only spent a total of about seven weeks there.

Its open windows, cavernous spaces, and towering ceilings made it impossible to heat. As a result, the château was never furnished permanently.

Each royal visit required a caravan of beds, tables, tapestries, and serving ware to be hauled in for a few days of sport and spectacle.

The emblem of the salamander, Francis I’s device, is everywhere—carved into ceilings, brackets, and friezes.

The creature, said to live in fire without being consumed, was meant to symbolize the king’s enduring strength and mystique.

In many places, it is accompanied by the letter “F” crowned in laurels, leaving no doubt about whose glory the building was meant to reflect.

Francis I, born in 1494 and reigning from 1515 until his death in 1547, was one of France’s most dynamic monarchs. A powerful patron of the arts and a central figure in the French Renaissance, he invited Italian artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, to his court. Da Vinci spent his final years in France and is believed to have brought the Mona Lisa with him—acquired by Francis and now housed in the Louvre.

Leonardo’s Spiral?

One of Chambord’s most famous features is its double helix staircase, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, though not definitively.

Whether the great Florentine actually designed it remains up for debate.

Still, its interwoven spirals, allowing two people to ascend and descend without ever meeting, are a marvel of Renaissance engineering and symbolism.

The staircase serves as the spine of the central keep, drawing visitors upward to the rooftop terraces where the surreal skyline comes into its own.

The Royal Apartments

Though Chambord was never fully completed, later monarchs did attempt to civilize its vast spaces.

Louis XIV ordered the construction of the Royal Apartments, creating a series of smaller, more intimate rooms with lowered ceilings and padded textile walls to insulate from the drafts.

Here, one finds fine furniture, carved fireplaces, and an array of decorative objects ranging from Chinese ginger jars to ormolu clocks.

Louis XV took a further step toward comfort, commissioning three enormous Dutch ceramic stoves to warm the apartments. One such stove now resides in the “coffee room,” where it was installed in the 18th century, moved into a niche from an earlier fireplace.

Manufactured in Danzig, the stoves were reassembled in Chambord in the late 19th century and are works of art in their own right. Each tile is moulded and painted with scenes of pastoral life, exotic animals, or whimsical architecture. Despite their practicality, they bring a decorative charm that aligns perfectly with Chambord’s blend of fantasy and function.

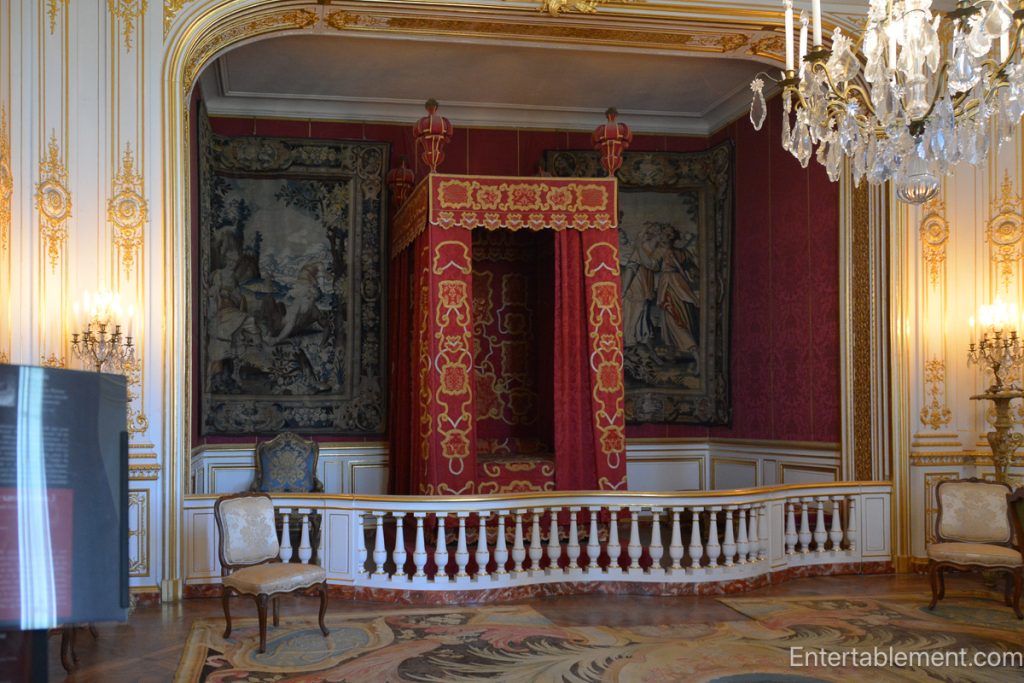

Among the most striking elements in the Royal Apartments are the richly adorned state beds—one cloaked in vibrant red velvet and another in deep blue damask.

These beds were more than functional; they were ceremonial. Used during the Ancien Régime as symbolic centers of power, the beds signalled royal presence. They were part of elaborate court rituals such as the king’s morning rising (lever) and evening retiring (coucher).

While these particular examples are likely reconstructions, they reflect the splendour and protocol of the Bourbon court, even when transposed to a lodge as impractical as Chambord.

Art, China, and a Liqueur Case

The château also holds an impressive collection of decorative arts. In one room, a set of imposing lidded ginger jars sits on a richly veined marble mantle, flanked by an intricate gilded clock and candelabra.

Another exhibit displays a striking “cave à liqueur,” or liqueur chest, from the 18th century. With etched glass decanters nestled inside a velvet-lined case, it would have been a fitting companion on a winter’s night—or, more likely, a gift of status and refinement.

Equally compelling is the porcelain service from the Chantilly manufactory, known as the “à la brindille” pattern. Produced in the second half of the 18th century, this blue-on-white twig motif became enormously popular and was widely copied by other factories. One set now displayed at Chambord is being reassembled piece by piece by the State, which began acquiring elements in 2013.

The Governor’s Apartments

One of the more finished spaces within the château is the Governor’s Chamber, used in the late 18th century by the Duke of Polignac under Louis XVI. The wallpaper and furnishings recreate the neoclassical elegance of the time, from floral tapestry panels to roll-top desks and velvet-upholstered chairs.

The adjacent rooms housed his valet and reflect a surprisingly domestic scale compared to the lofty halls elsewhere.

As the Revolution approached, the Polignac family fled, and the château’s contents were sold at auction. Like so many royal spaces, Chambord became a ghost of its former life—its grandeur intact but its occupants scattered.

The Rooftop Dreamscape

One of Chambord’s most magical experiences awaits at the very top.

The rooftop terraces, accessed via the double helix staircase, offer panoramic views of the estate and a close-up look at the fantastical rooftop skyline.

Turrets and lanterns, open-air walkways, decorative spires, and a central lantern tower soar like a stone forest against the sky. The architecture blurs the line between fortress and fantasy.

From this vantage point, it’s easy to see how Chambord was intended not as a home but as a symbol—a showpiece of Renaissance might, creativity, and royal prestige.

Looking out over the surrounding game-rich forests, one can imagine the royal parties below and the pageantry that unfolded here, even if only for a few fleeting days.

From Royal Ghost Town to National Treasure

In modern times, Chambord has been reimagined as a public monument, cultural venue, and site of ongoing restoration. Though it never served as a true home, it remains one of the most dramatic and fantastical expressions of Renaissance ambition. Its contradictions are its charm: designed to dazzle but never meant to endure daily life, grand but curiously cold, symbolic yet strangely serene.

A Landscape for Leisure

Despite its monumental size, the Château de Chambord was not designed with formal gardens in mind. Chambord’s landscape was shaped by its primary purpose as a hunting retreat, unlike the manicured grounds of Versailles or Chenonceau. The château sits in the heart of what remains the largest enclosed forest park in Europe, spanning over 13,000 acres—an expanse more wild than refined.

One notable exception is the Grand Canal, which began in 1523 during the initial construction but was only completed under Louis XIV in the 17th century. Stretching nearly five kilometres, it beautified the grounds and was a practical tool for draining the marshy terrain. Today, it reflects the château’s striking silhouette, offering long sightlines from the upper windows.

Scattered around the estate are ancillary buildings, including what appears to be a chapel, likely associated with the 19th-century occupation by the Count of Chambord. These outbuildings supported the royal hunting parties, housing staff, horses, and provisions, and now offer glimpses into the estate’s more utilitarian past.

A Stage for the Present

Today, Chambord continues to serve as a setting worthy of its splendour. It has been featured in numerous films and television series, providing a cinematic backdrop for period dramas, historical documentaries, and even fantasy productions. Its blend of theatrical architecture and untouched grandeur makes it an irresistible location for filmmakers and photographers alike. Occasionally, the château hosts concerts, exhibitions, and special events, seamlessly merging its past as a royal spectacle with its current role as a cultural landmark.

Even in the gift shop, the spirit of Chambord lingers. Among the souvenirs is a set of Gien plates featuring French châteaux—an echo of the ornate, impractical beauty that defines the building itself. Because, really, what could be more appropriate than commemorating a hunting lodge built like a palace with a dinner plate fit for a king?

I set a table with the plates, which you can see over at Entertablement — Tables from the Loire: A Spring Table with Gien’s Château series.

This post is part of the Loire Valley Château Series—a journey through the elegance, history, and charm of France’s most beloved estates.

Explore the full series:

- Château de Chenonceau

- Château de Chambord

- Château de Chaumont

- Château de Cheverny

- Château de Villandry