“Hardwick Hall, More Glass than Wall”

Rising imperiously from the Derbyshire landscape, its vast windows glitter in the sunlight, a defiant statement from its formidable creator.

Bess of Hardwick, the woman who outpaced four husbands, amassed a staggering fortune, and left behind one of Britain’s most architecturally significant Elizabethan houses. If ever there was a house that embodied its owner, Hardwick is it.

“Hardwick Hall, More Glass than Wall” — The adage, coined by Bess’s contemporaries, speaks to the audacity of its design. At a time when glass was an expensive luxury, Bess flaunted her wealth with towering walls of leaded panes, surmounted by a parapet in which her initials, ES, stood for Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury (her fourth husband was the Earl of Shrewsbury).

The result? An ethereal lightness is uncommon in the defensive architecture of earlier Tudor homes. Hardwick was not built for battle—it was built to be seen.

But there is more to Hardwick than its iconic windows. Step inside, and you’re met with soaring ceilings, walls draped in exquisite tapestries, and furniture inlaid with the most intricate marquetry—each piece a whisper of the wealth and status Bess so meticulously cultivated.

Hardwick Old Hall: The Predecessor

Before the glittering Hardwick Hall was completed, Bess of Hardwick resided in Hardwick Old Hall, the now-romantic ruin still nearby.

Built in the 1580s, the Old Hall was an ambitious project but was soon eclipsed by the grandeur of its successor. Yet, it remains an essential part of Hardwick’s story, offering insights into Elizabethan domestic life.

Visitors can explore its skeletal remains, imagining the world of Bess before her final architectural triumph. The remnants of exquisite plasterwork hint at the refinement to come, while the structure starkly contrasts with the light-filled luxury of the newer Hall.

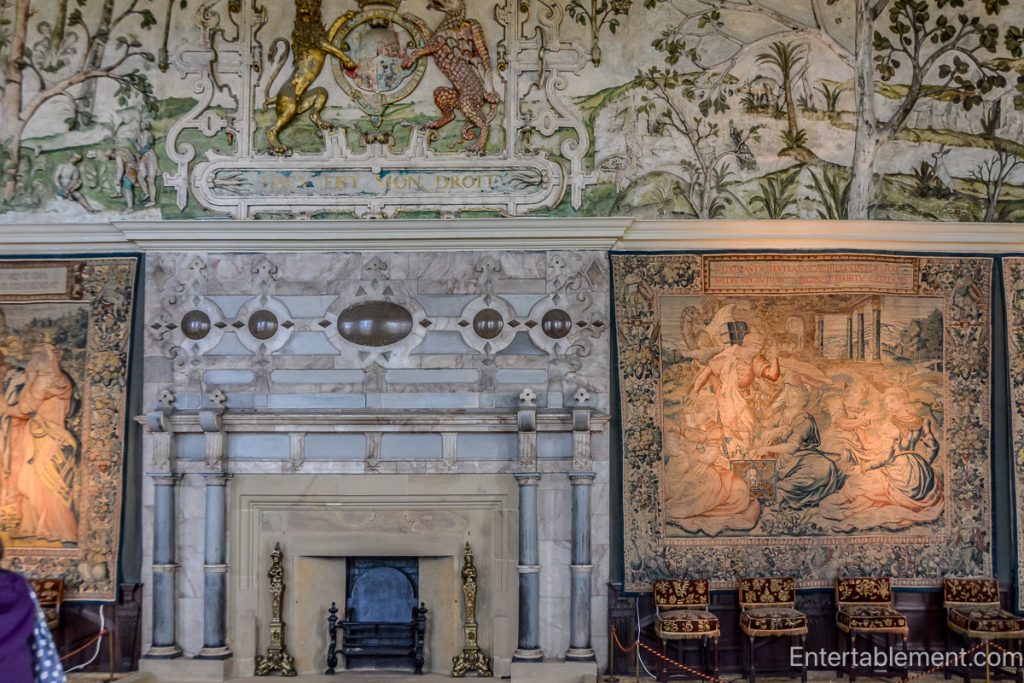

The Great Hall and its Plaster Cornice

The Great Hall of Hardwick is a spectacular space designed to impress. Dominated by vast tapestries and intricate carvings, it is crowned by an extraordinary plaster frieze that runs along the upper walls.

The frieze depicts a lush, fantastical forest teeming with animals, mythical creatures, and classical figures.

This elaborate decoration serves as a statement of wealth and an intellectual display, reflecting the Renaissance fascination with allegory and storytelling.

The immense fireplace, adorned with heraldic symbols, anchors the room and emphasizes Hardwick’s function as a social and political power centre.

A World of Tapestries

To walk through Hardwick is to walk through a gallery of the woven arts. Once as valuable as gold, tapestries line the vast rooms, cocooning visitors in the rich hues of Renaissance storytelling.

It’s a dizzying display, and I confess I didn’t fully appreciate the distinctions between the various tapestries on my visit. I’m eager to return and see them again with a more discerning eye.

The famous Gideon Tapestries, depicting the biblical hero’s triumphs in a swirl of deep blues and gilded details, were not hanging when I visited, but here is a link to the National Trust’s site telling of their conservation efforts and teh rehanging of the tapestries in 2023.

See what I mean—they’re everywhere! The astoundingly valuable Flemish weavings recount classical and allegorical scenes, tangible evidence of Bess’s education and cultural aspirations.

Not only that, but the bed hangings are rich brocade, hung from a carved and painted tester—a monumental display of wealth and opulence.

The Marquetry Marvel: Games and Symbolism

Among Hardwick’s treasures is an astonishing marquetry table, its surface an exquisite puzzle of inlaid designs.

Look closely; playing cards are scattered in artistic disarray—spades, hearts, clubs, and diamonds, each painstakingly crafted from wood veneers.

Beside them, backgammon and chequers boards are inlaid into the table, a nod to leisure and strategy.

It’s remarkable for its craftsmanship and what it represents—a world where power and politics were as much a game as the ones played upon it.

The Burden of Hosting Mary, Queen of Scots

One of the most politically charged aspects of Bess’s life was her role in the prolonged captivity of Mary, Queen of Scots.

From 1569 to 1584, Mary was held under the watchful eye of Bess and her fourth husband, George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. Although she spent much of this time at Chatsworth House, she was also lodged at Hardwick Old Hall several times. The Earl of Shrewsbury was required to provide not just accommodation but also a full household for Mary, including servants, guards, and a suitable courtly environment. This costly obligation was a source of endless frustration and political manoeuvring as factions at Elizabeth I’s court debated Mary’s fate.

Mary’s presence placed enormous strain on Bess’s marriage, as the financial burden of housing a deposed queen and the constant political intrigue surrounding her proved overwhelming. Bess and Talbot eventually separated, with Mary’s imprisonment exacerbating their already-strained relationship.

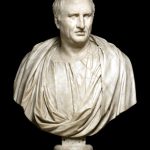

This portrait was painted by an English artist when Elizabeth I (1533–1603) was in her sixties. Don’t let the red hair fool you — it was a wig. The image reflects the tradition of painting the queen as a timeless beauty.

Despite the political tensions, Mary and her ladies-in-waiting found ways to occupy themselves, including needlework. Several surviving tapestries and embroideries—now known as the Oxburgh Hangings—testify to Mary’s long hours in confinement.

Some of these pieces even feature subtle messages and symbols reflecting Mary’s longing for freedom and her claim to the English throne.

Arabella Stuart: A Life in the Shadows

But for all its beauty, Hardwick also has a shadowed history, one of thwarted ambition and royal intrigue. Enter Lady Arabella Stuart, Bess’s granddaughter and once a serious contender for the English throne. Groomed from birth as a potential heir to Elizabeth I, Arabella was trapped by her noble bloodline.

Her marriage to William Seymour, conducted in secret, sealed her fate. Fearful of rival claimants, James I imprisoned her in the Tower of London. She died there, likely of self-imposed starvation, a tragic contrast to the glittering fortune that built Hardwick.

Walking through the house, one cannot help but wonder—did Arabella gaze from these vast windows, longing for a future that was never to be?

Victor and Evelyn Cavendish: The Modern Connection

Hardwick Hall’s story does not end with Bess. In the early 20th century, Victor Cavendish, later the 9th Duke of Devonshire, and his wife, Evelyn, played a significant role in maintaining the estate’s grandeur. Their bedroom contains an enormous tester bed with exquisite hangings.

The dressing table adds an Edwardian-era note to the historic suite.

Evelyn, a well-travelled and politically engaged woman, spent time abroad while her husband served as Governor-General of Canada.

She returned to England with mixed feelings, balancing her responsibilities as the mother of daughters needing advantageous marriages and managing a vast estate.

Their contributions ensured Hardwick remained a thriving historical landmark rather than a relic of the past.

The Kitchens: The Heart of Hardwick

No grand estate could function without its kitchens, and Hardwick’s was no exception. The Victorian-era kitchen complex, complete with multiple workstations, was a hub of activity.

I’m always fascinated with the behind-the-scenes areas of grand houses.

While more up-to-date than the kitchens of Bess’s era, the functions remain the same. For centuries, servants prepared lavish meals for the household, using game from the surrounding estates, fresh produce from the gardens, and imported spices.

Closed stoves fill the enormous hearth where meat would have roasted on spits in Elizabethan times.

Copper pots gleam on shelves, awaiting their next use.

A massive lidded copper cauldron with an efficient spout at the bottom kept hot water at the ready.

The servants’ hall nearby ensured those working tirelessly behind the scenes were fed, creating a self-contained world within Hardwick’s walls.

Victorian plates offer moral maxims for the diners.

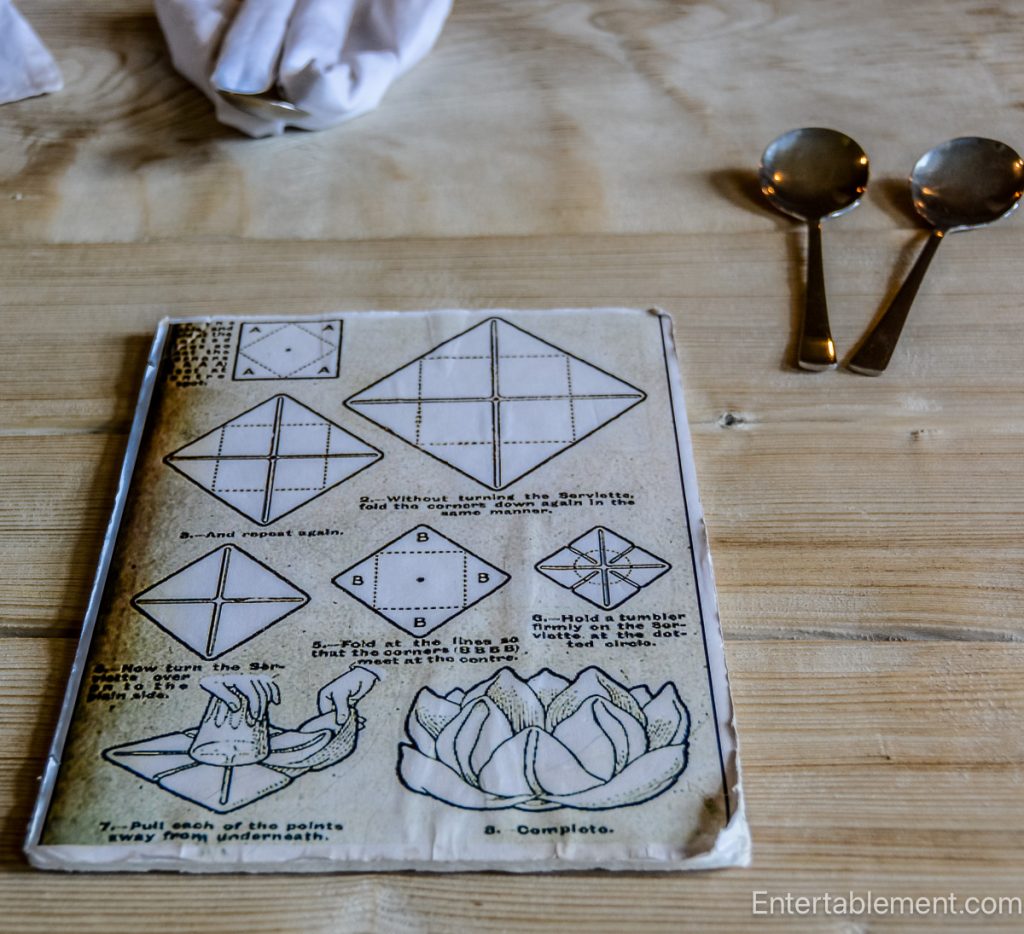

Nearby, we find instructions for folding napkins into a flower…

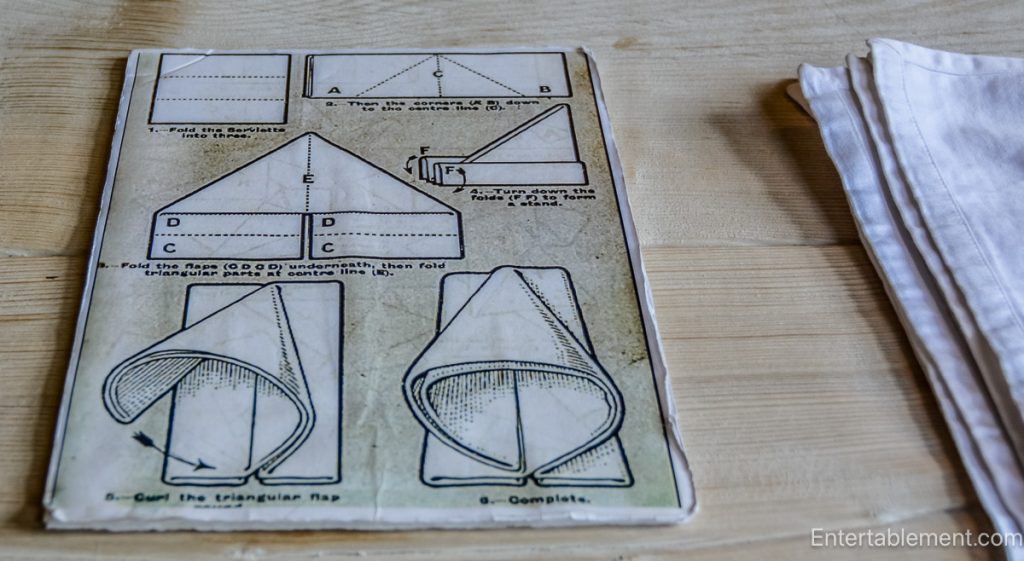

… and a more formal Bishop’s Mitre.

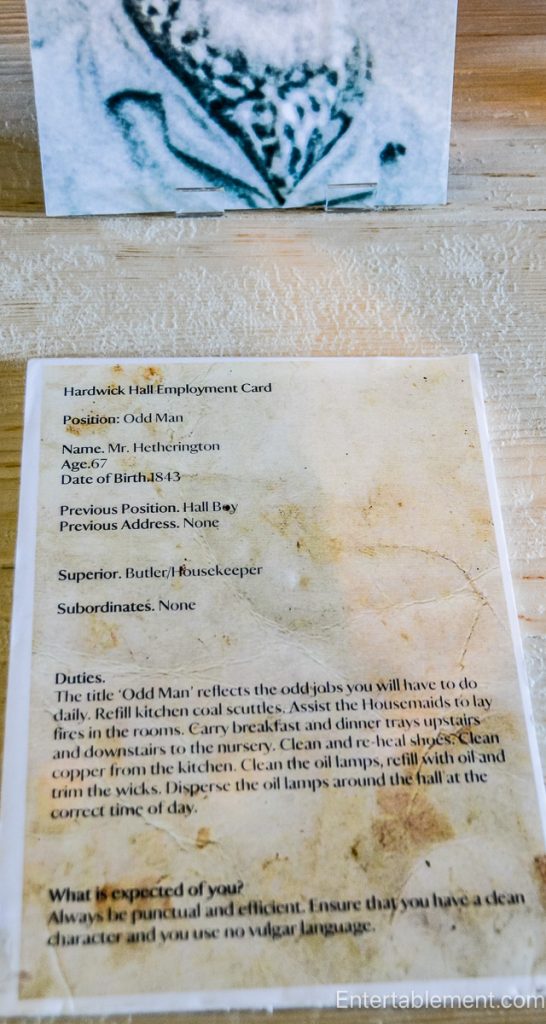

Servants and the “Odd Man”

Behind Hardwick Hall’s opulence was a carefully orchestrated workforce essential to maintaining the estate’s grandeur. The servants’ world functioned out of sight, but their roles were pivotal. Mrs. Frances Burgess Stent, aged 51, had risen to Housekeeper from Assistant Housekeeper at nearby Chatsworth.

One particularly intriguing figure was the Odd Man—a jack-of-all-trades who performed various tasks around the house and estate.

From running errands to assisting in the kitchens or stables, Mr Hetherington, the Odd Man, aged 67, looks to be a reliable sort, doesn’t he? His role was ever-changing, ensuring the smooth operation of Hardwick Hall. This flexibility was essential in such a large household, where servants had strictly defined roles, but additional hands were always needed for unexpected tasks/

The Gardens: A Living Legacy

Outside, Hardwick’s gardens offer a more contemplative beauty.

Carefully restored, they blend formality with the wild exuberance of herbaceous borders.

The Orchard and Walled Garden hint at the estate’s Tudor past, while vibrant blue agapanthus and billowing grasses soften the structured terraces. A white-painted bench nestled beside an explosion of blooms invites visitors to pause and take in the sculpted stone balustrades and topiary—a moment of quiet amid the bold statements of the Hall itself.

Enduring Influence

Hardwick Hall remains one of England’s most significant country houses, symbolizing the rise of an extraordinary woman who defied societal expectations.

Today, under the stewardship of the National Trust, it continues to captivate visitors, its treasures revealing new layers with every visit.

Hardwick Hall delivers for those who love history, architecture, or simply a story of sheer, unapologetic ambition.