Britain in 410 was a well-integrated, Latin-speaking Romano-British society. But trouble was brewing—Saxons and Picts were stepping up their invasions along the East Coast, and local leaders sent a plea for help to Emperor Honorius in Italy. But Rome was struggling with overexpansion and had no help to spare. Sorry, folks; you’re on your own.

The Roman legions packed up and left.

What happened next is somewhat confusing. The old tale—told by the Welsh monk Gildas and later amplified by the Venerable Bede—paints a dramatic picture: a brutal Saxon invasion that destroyed or drove westward the native Celts and their language. But modern historians, like Susan Oosthuizen, don’t buy it. There’s no solid evidence of a systematic invasion, just the usual raids Britain had always faced from across the North Sea.

Instead, it seems that Britain simply drifted back to its pre-Roman ways. The grand Roman towns, villas, and roads crumbled, left to decay. Britain didn’t fall to a bloody genocidal conquest—it quietly stepped back in time.

The tribal chiefs and warlords reclaimed their places, and society became hierarchical. At the top were kings and lords who controlled land and resources; below them were thanes (nobles) and free peasants who worked the land. Everyone else was a serf or slave, tied to the land and the service of their lords.

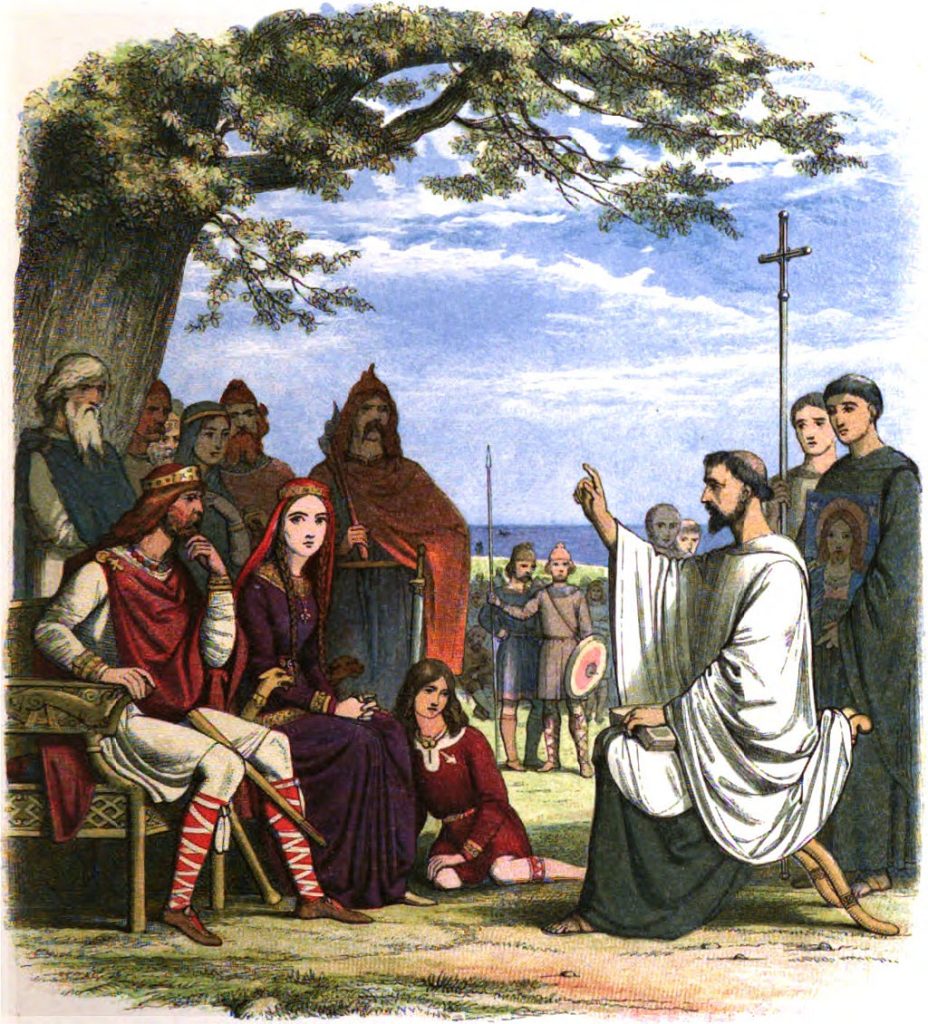

Paganism resurged in the eastern regions until St. Augustine came to Kent in 597, re-establishing Christianity. In the west—Wales, Ireland, and beyond—Celtic Christianity flourished, inspired by saints like St. Patrick, St. Ninian, and St. Columba.

The Church exerted a powerful influence over governance, education, and culture. Monasteries acted as centres of learning, spiritual practice, and economic activity. Illuminated manuscripts such as the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Book of Kell, and Old English literature, including Beowulf, emerged during this period.

Innovations in farming included the widespread use of the heavy plough, better suited to northern Europe’s clay-rich soils. Crop rotation practices improved efficiency and productivity.

The Anglo-Saxons were skilled metalworkers with sophisticated gold, silver, and enamel craftsmanship, revealed at excavations such as Sutton Hoo. Blacksmithing and carpentry flourished, leading to advancements in tools and weaponry.

Building construction moved backwards, however, with the Romans’ departure. The Romans took their highly sophisticated techniques for quarrying, shaping stone, and making bricks with them. Their road-building skills were particularly well-developed. We can only marvel at such thoroughness given Britain’s pothole-strewn roads today.

Not only were Roman roads exceptionally well built, but they were also extensive. Wow!

A collective amnesia settled over the construction crews left behind. Buildings reverted to timber or wattle and daub, all subject to rapid deterioration, leaving minimal remains from this period.

Early churches were built primarily from timber, later transitioning to stone as techniques improved. Stone churches at Escomb and St. Peter’s Church in Wearmouth are notable examples.

Manor houses were modest, centred around a great hall for living, feasting, and administration. They were characterized by simplicity and practicality, sometimes displaying intricate carvings or decorations on timber structures. In time, they became more complex, adding ancillary buildings for storage, workshops, and living quarters for peasants or serfs. Sited close to water and arable land, they were built for defence and to reflect the lord’s wealth and status.

In the later 8th century, the Vikings—Scandinavian seafarers from modern-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden—began to invade Britain. They laid waste to Lindisfarne Priory in 793, marking the start of the Viking Age in Britain.

At first, the Vikings targeted monasteries and towns. Soon after, they built significant settlements in eastern and northern England, where they ruled under Danelaw and founded major towns like York (Jorvik), leaving a lasting impression on local culture and governance.

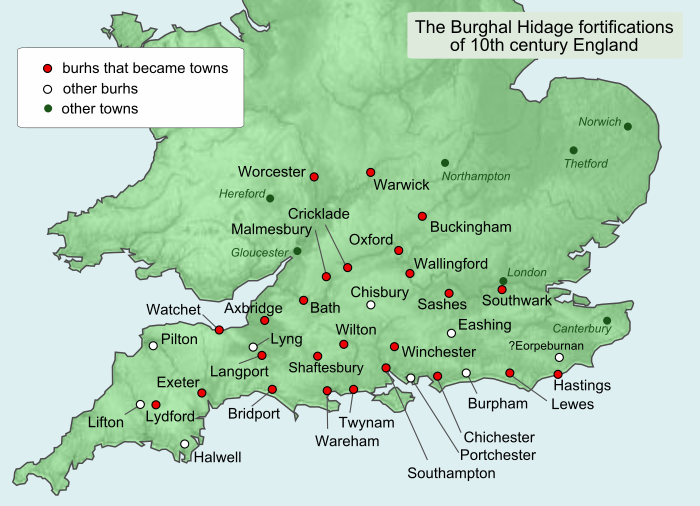

The Viking invasions forced Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to unite against a common enemy, particularly under leaders like Alfred the Great of Wessex. Alfred established fortified towns (burhs) and reorganized the military to resist Viking advances. Treaties, such as the division of England between Wessex and the Danelaw, shaped the political landscape.

Viking settlers intermarried with the local population, contributing to Britain’s cultural and genetic makeup. Norse place names, such as those ending in “-by” (e.g., Grimsby, Whitby), remain a testament to their influence. The Anglo-Saxons laid the foundation of English culture, language, and governance. The Vikings introduced Norse culture, language, and innovation elements, such as advanced shipbuilding.

The culmination of the Saxon era was the momentous coronation of Edward the Confessor, who reigned from 1042 to 1066 as king of a newly unified Britain. His lineage was divided—his father was Saxon, his mother Norman—and Edward himself, raised in exile across the Channel, spoke French rather than the tongue of his forebears.

Upon ascending the throne, Edward made a significant shift in the realm’s political landscape. Though he formally transferred the seat of power from Winchester, the ancient capital of Wessex, to London, he had no desire to entangle himself with the Anglo-Danish faction that still wielded influence there. Instead, he established his court in Westminster, setting a precedent that would shape London’s destiny for centuries to come.

Westminster became a royal enclave, housing a palace, an abbey, and a monastery. The design of Westminster Abbey was inspired not by Saxon tradition but by the great Jumieges Abbey in Normandy, where Edward had spent much of his youth.

Westminster Abbey was a strikingly Norman structure. Its nave was lined with arcades that concealed the aisles below, rising to a clerestory that allowed light to flood the upper reaches of the building. Smaller than the current structure, it had a central tower. Its foundations still exist beneath today’s Abbey, along with sections of the monastic dormitory in the undercroft.

Westminster Abbey today

At Edward’s death in 1066, the new abbey was still incomplete. Yet it would soon take on a role of profound significance, for within its unfinished walls, William the Conqueror was crowned following his victory at the Battle of Hastings, marking the dawn of Norman rule in England.