He wore the mitre like a crown—and took his martyrdom like a coronation.

Let’s talk about Thomas à Becket, one of medieval England’s most controversial saints—and arguably one of its least humble.

On paper, he’s a martyr: murdered in a cathedral for standing up to a king. In reality? A bit more complex.

Becket was ambitious, politically savvy, and never met a gesture he couldn’t turn into theatre. Yes, he was pious. Yes, he stood up for the Church. But he also helped plant the seeds of ecclesiastical supremacy that would choke royal authority for centuries.

Martyr? Maybe.

Manipulator? Almost certainly.

The Rise of a Clerk with Swagger

Becket came from modest beginnings—London-born, well-educated, clever. He rose quickly in royal service, thanks to a sharp brain and even sharper ambition. By the 1150s, he was Henry II’s right-hand man, holding the powerful post of Chancellor.

As Chancellor, Becket:

- Collected taxes from the clergy

- Rode to war in fine armour

- Lived in a style that made bishops blush

He was, by all accounts, more courtier than cleric. So when Henry tapped him to become Archbishop of Canterbury, it looked like a masterstroke—put your loyal man in the Church’s highest seat and finally get those meddlesome priests under royal control.

Except Becket had other ideas.

The Great Transformation (Or PR Coup?)

Almost overnight, Becket went from silk-clad royalist to hair-shirted holy man. He resigned the chancellorship. He picked fights with Henry over jurisdiction, especially whether clergy could be tried in royal courts.

This wasn’t just principle—it was power. Becket was asserting that the Church had legal immunity, a claim that threatened to unravel everything Henry had worked to centralize in the justice system.

Becket wasn’t negotiating. He was drawing battle lines, and he did it with flair:

- He excommunicated royal allies

- Refused compromise

- Cast himself as a suffering servant, persecuted by worldly powers

If this sounds less like humility and more like a public branding campaign, you’re not wrong.

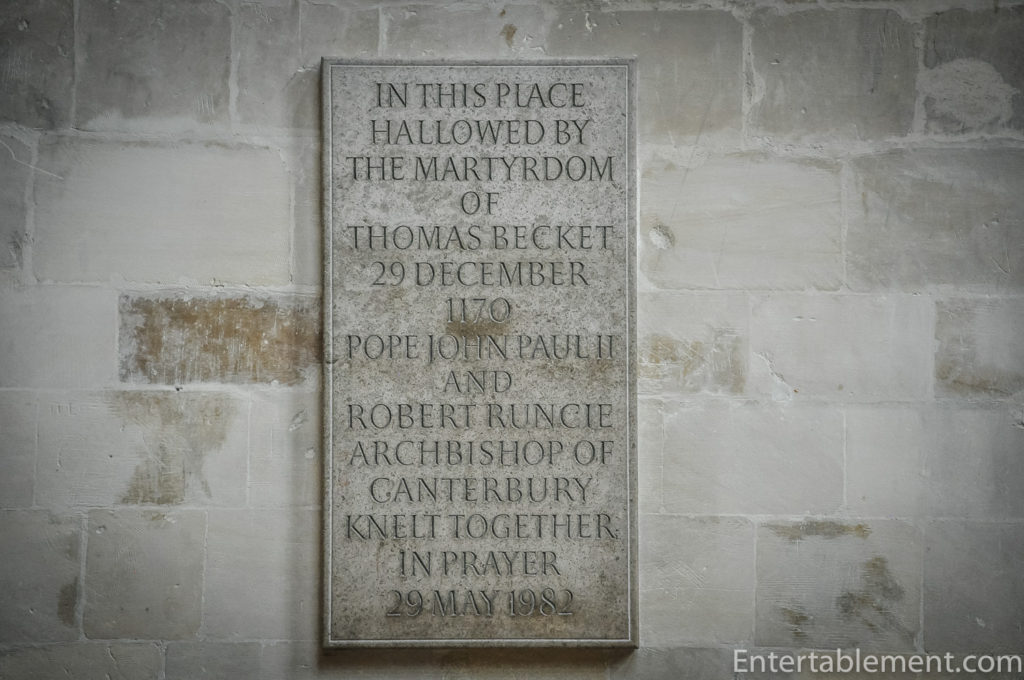

Murder in the Cathedral

Frustrated and outmaneuvered, Henry II reportedly lashed out:

“Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?”

Four knights heard those words, stormed Canterbury Cathedral, and hacked Becket down in front of the altar.

The murder shocked Europe—and catapulted Becket into sainthood.

Pilgrims flocked to his shrine. Miracles were reported. Becket was canonized in just three years—one of the fastest in Church history.

Saint or Symbol?

In death, Becket became everything the Church needed:

- A martyr to papal authority

- A symbol of spiritual purity against royal corruption

- A reason to assert ecclesiastical power across Europe

But make no mistake—he played the game while alive, too. He provoked, postured, and refused to settle even when it might have prevented bloodshed.

He may have been sincere in his beliefs, but he was also very good at weaponizing them.

Legacy

Becket’s legacy is… complicated:

- He inspired centuries of defiance against kings within the Church.

- He contributed to the long rift that would eventually explode in the Reformation.

- His shrine became one of the most visited pilgrimage sites in Europe—until Henry VIII had it obliterated as part of his own showdown with Rome.

By then, Becket had become less a person than a symbolic bludgeon.

Final Thought

Some men rise through faith. Others rise through politics. Becket rose through both, and when the two collided, he leaned into martyrdom with dramatic flair.

Whether you see him as a saint or a schemer depends on how much weight you give to motive versus effect. But one thing’s clear: he didn’t die quietly. And he made sure the world never forgot it.